TYPE: Research Article![]()

RECEIVED 23 July 2025

ACCEPTED 24 November 2025

PUBLISHED 22 December 2025

Abstract

Human–carnivore conflict (HCC) is a major conservation and livelihood challenge in the Indian Himalayas. In Himachal Pradesh, leopards (Panthera pardus) and black bears (Ursus thibetanus) are widespread, but research has mostly focused on protected areas, leaving human-dominated landscapes understudied. This study investigates HCC in Kangra district, Himachal Pradesh, between January 2014 and August 2022, with emphasis on livestock depredation, human casualties, and spatio-temporal trends. Conflict records were compiled from four divisional forest offices (N=193) and supplemented with semi-structured interviews (N=86) to assess species involved, type of conflict, and compensation status. Results revealed that leopards were the primary cause of livestock depredation, targeting goats (57.42%) and sheep (26.45%), while black bears were more often involved in direct human encounters. The Nurpur Forest Division reported the highest number of cases (N=72) with 421 livestock deaths followed by Palampur (N=54), Dehra (N=51), and Dharamshala (N=24). Seasonal analysis showed conflict peaks in the rainy (N=59) and summer (N=58) seasons. Leopard depredation was highest in summer and rainy months, while black bear incidents peaked in autumn. Statistical analysis confirmed a significant upward trend in leopard attacks over the study period (R²=0.74, p=0.0059). The findings highlight the growing intensity of HCC outside protected areas and underscore the need for mitigation strategies, including predator-proof livestock enclosures, awareness programs, and timely compensation to reduce retaliatory attitudes and promote coexistence.

Keywords: Conflict mitigation, Himalayan black bear, leopard, livestock depredation, Indian Himalayas.

Introduction

Since ancient times, humans and wild animals have competed for the same natural resources (Chauhan & Rajpurohit 1996; Madhusudan 2003; Distefano, 2005), which has now intensified into Human-Wildlife Conflict (HWC), threatening both biodiversity and human livelihoods. The conflict resulting in livestock loss and crop destruction leads to problems of food security and poverty (Gemeda & Meles, 2018). Large carnivores are among the most frequent conflicting species, with leopard, black bears, snow leopard, wolves, brown bears, and tigers often central to these conflicts, causing significant human and livestock losses across India (Madhusudan, 2003; Distefano, 2005; Suryawanshi et al., 2013; Das, 2018; Sharma et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2021), making human-carnivore conflict (HCC) a significant constituent of HWC. In the Indian Himalayas, an increase in human-leopard conflicts has been linked to changes in land use (Chauhan et al., 2002). HWC presents a significant challenge across Himachal Pradesh (Sharma, 2024 a & b). The region holds considerable geomorphological and ecological importance, with its altitudinal variations supporting a diverse range of flora and fauna. But with the rapid transformation in land use changes and deforestation due to developmental activities, the state is facing numerous challenges that threaten its biodiversity. Moreover, the expansion of road networks and agricultural land has further led to an escalated confrontation with humans. Socially, the consequences of HWC are inextricably linked to human livelihoods and community dynamics (Hill, 2021).

Although leopard (Panthera pardus) and black bear (Ursus thibetanus) are widely spread throughout Himachal Pradesh, and several studies have focused on HWC in protected areas of the state (Mohanta & Chauhan, 2014; Rathore & Chauhan, 2014; Bhardwaj et al., 2024; Kichloo et al., 2024), little research has addressed non-protected landscapes where the majority of the population coexist. The region outside the protected area is often in conflict with the leopard and black bear (Sharma, 2024 a & b). About 94% of the human population in Kangra district resides in rural areas (Census, 2011) and depends heavily on livestock. This region also serves as a migratory route for pastoralists (Sharma et al., 2022). The traditional annual movement of the Gaddi community to ensure food availability for the livestock often increases the risk of predation by the large carnivores. These factors heighten the risk of carnivore attacks, yet systematic documentation outside protected areas remains scarce. Mahajan (2020) and Sharma (2024 a & b) highlighted the issue of leopard and black bear conflict across protected areas of Himachal Pradesh. In the present study, we try to identify conflict trends across non-protected landscapes of the district Kangra by examining human–carnivore conflict cases that occurred between January 2014 and August 2022, focusing on livestock depredation and human casualties. The findings of our study support conflict mitigation and long-term conservation planning. We hypothesize that human–carnivore conflict in Kangra has shown an increasing trend over the years. To test this, we examined conflict patterns across years, seasons, and forest divisions (FD) while assessing compensation effectiveness.

Methods

Study area

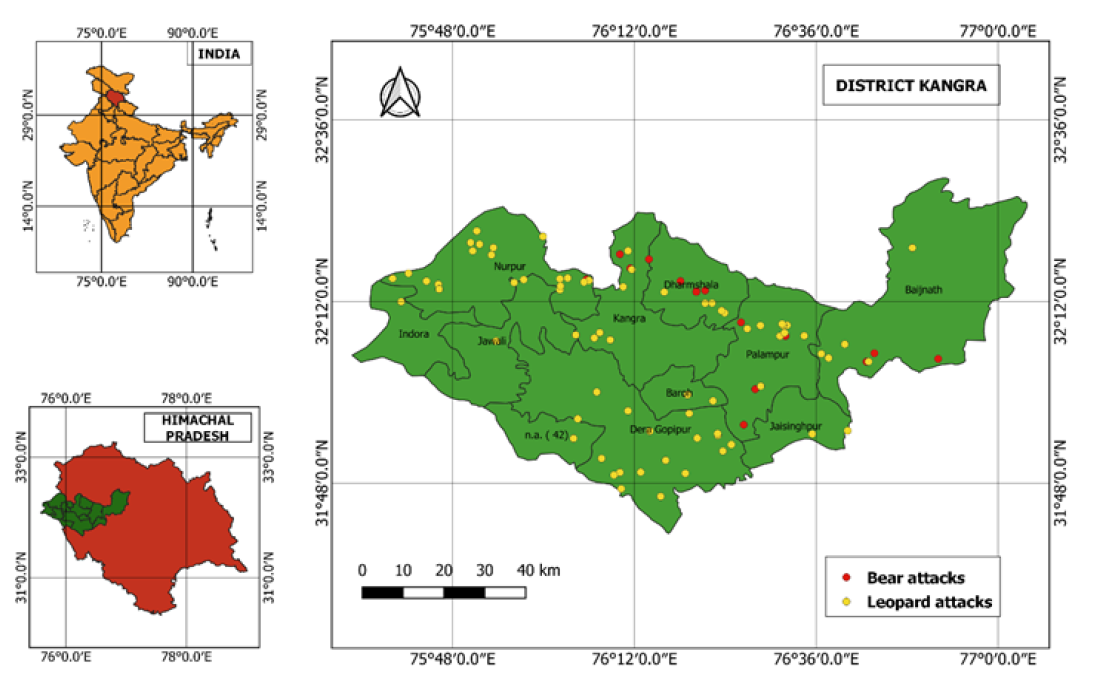

The state of Himachal Pradesh is well-known for its dense forests, rugged terrain, and high mountains. A key determinant of the district climate is its varying altitude, supporting an incredible diversity of wildlife. Among the 12 districts of Himachal Pradesh, Kangra district lies between 30° 22′ 40″ and 33° 12′ 40″ north latitude and 75° 45′ 55″ and 79° 04′ 20″ east longitude (Figure 1) with a geographical area of 5,739 km2. It is bordered by the districts of Lahaul and Spiti to the northeast, Chamba to the north, Mandi to the south, Kullu to the east, and the Punjab state to the west. Kangra district is distinguished by its topography, characterized by intersecting mountain ranges that enclose broad to narrow valleys. Situated in the Shivalik and Lesser Himalayan zones, the district’s landscape is defined by a series of nearly parallel hill ranges that progressively rise in height towards the northeast. The climate of the region has four distinct seasons: Summer (March-June), Rainy (July-September), Autumn (October-November), and Winter (December-February). In the low-lying valley areas, situated below 600 meters, the climate is hot and humid. At elevations between 2,000 and 4,500 meters, the district experiences a cold, temperate climate, with heavy snowfall during the winter months from December to February. During the monsoon season, from July to September, the landscape transforms, turning lush and green due to the abundant rainfall. According to the assessment for 2021, the district has a forest area of 2,357.27 km2, which is 41.08 % of its total geographical area (Forest Survey of India, 2021). The Kangra forests are home to a wide variety of plants, including Chir (Pinus roxburghi), Banj oak (Quercus leucotrichophora), deodar (Cedrus deodara), Kharsu oak (Quercus semecarpifolia), Kail (Pinus wallichaina), spruce (Picea sp.), and fir trees (Abies sp.), as well as numerous species of wild animals, including the common leopard, black bear, jackal (Canis aureus indicus), sambar deer (Rusa unicolor), and nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus). The district has two protected areas, namely the Pong Dam Lake Wildlife Sanctuary (207.59 km2), a Ramsar site of international importance that potentially offers a resting reserve for the migratory birds coming from the Trans Himalayan zone in the winter season, and the Dhauladhar Wildlife Sanctuary (982.86 km2), unique in its high rainfall and rain shadow zones. The study area, having habitat for leopard and black bear, harbors a good population of both species, often resulting in conflict.

Data Collection and Methodology

Information on HCC incidences in the study area was collected through in-person interviews and official records from four divisional forest offices. Villages were purposively selected based on reported incidences of livestock depredation and human attacks recorded by divisional forest offices, as well as their proximity to forested areas. Within these villages, households were then selected using random sampling to ensure unbiased representation at the household level. The interviews were carried out between April and June 2022, and information was collected for the period January 2014-August 2022. A semi-structured questionnaire, comprising both open and closed-ended questions, was administered to 86 individuals, falling within the age group of 20-70 years, of whom 53 reported experiences of conflict during the study period. Verbal consent was obtained from all participants prior to the data collection, and no information that could identify individuals was recorded. From the questionnaire, we gathered details on the species involved in HCC, the type of victim (human or livestock), year and month of the attack, type of conflict, and residents’ awareness of the compensation scheme. In addition, systematic data were collected in person from official records maintained by the Nurpur Forest Division, Dharamshala Forest Division, Dehra Forest Division, and Palampur Forest Division. A total of 193 reported cases were obtained from these offices. In cases where incidents were present in both primary (interview-based) and secondary (official record-based) datasets, the information from the secondary source was prioritized to maintain accuracy. The final dataset comprised 201 conflict reports from both sources.

This study focused on incidents involving leopards and black bears to assess the intensity of HCC in the region. To ensure data reliability, only cases with verifiable information were included. Spatial mapping was conducted using QGIS 3.16 Hannover. Based on reported cases, efforts were made to identify seasonal patterns of attacks, determine the most vulnerable periods, and assess trends over time. Furthermore, details of compensation payments were also collected from forest department records to evaluate the economic impact of such conflicts.

Data Analyses

The overall data collected on HCC incidents from January 2014 to August 2022 were analyzed in relation to time, area, incident type (injuries and fatalities for livestock as well as humans), and loss in terms of the most depredated livestock species with respect to the incidence. The quantitative data were analyzed using linear regression to assess the trends in HCC. A trend was deemed statistically meaningful if the coefficient of determination (R²) was ≥0.65 and the p-value was ≤ 0.05 (Bryhn & Dimberg, 2011). We used the chi-square test (ɑ=0.05) to check the seasonal difference in the number of attacks by both predators. To further illustrate conflict patterns, the species involved, and financial compensation, bar graphs and maps were employed for visual representation. For statistical analysis, the yearly data were analyzed for the years 2014-2021, and data were collected till August for the year 2022. In case of monthly data, the missing information for any period was straightforwardly not included for analysis, resulting in a total of 190 cases. This approach helped to reduce the bias in the conclusion.

Results & Discussions

Species Involved in Human-Wildlife Conflict

Leopards and black bears were identified as the primary conflict-causing species (Sharma, 2024 a & b) in the non-protected landscapes of district Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, which significantly contributed to livestock depredation and human casualties. In addition to these large carnivores, other mammalian species, including the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta), wild boar (Sus scrofa), nilgai, and sambar deer, were identified as primarily responsible for crop damage. A few instances of monkey and wild boar attacks on humans were also reported. From January 2014 to August 2022, leopards accounted for 181 cases and black bears for 20 cases out of total 201 conflict cases.

Figure 1. Locations of leopard and black bear attacks in the Kangra district the years 2014-2022.

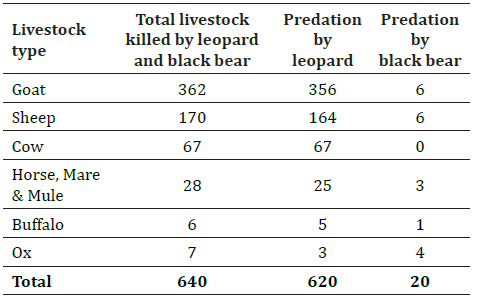

Livestock depredation by leopards and black bears

Between January 2014 and August 2022, a total of 177 recorded attacks on livestock resulted in the death of 620 animals. Leopards preyed on goats, sheep, cows, horses, mares, mules, oxen, and buffalo (Table 1). Goats were the most frequently killed species (57.42%), followed by sheep (26.45%) and cows (10.81%). Black bears were responsible for nine attacks on livestock, resulting in the death of 20 animals, with goats and sheep accounting for 30% each, followed by oxen (20%), buffaloes (15%), and horses (5%).

The relationship between leopard attacks and bear attacks on different livestock types was not statistically significant (R2= 0.442, p>0.05); however, a positive slope (0.0121) indicates

Table 1. Livestock predation by leopard and black bear in Kangra district during the years 2014-2022

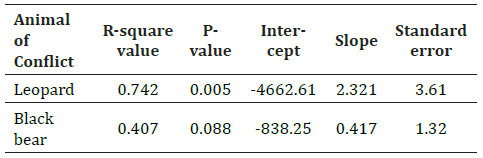

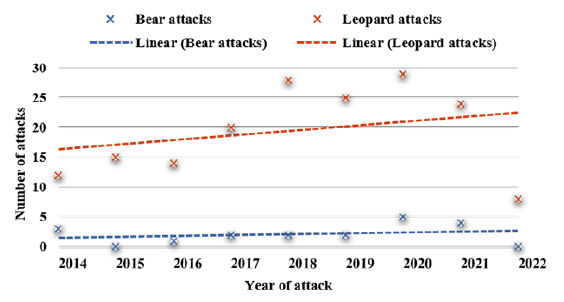

that bear attacks tend to increase slightly as leopard attacks increase. In the case of leopard, the number of attacks decreased sharply as we move from medium-sized livestock (e.g., goat and sheep) to large-sized livestock (e.g., ox), showing a high preference for medium-sized livestock (R2=0.787, p<0.05), whereas black bear shows a little variation in attacks for different livestock (Supplementary Table S1). Incidents of leopard and bear attacks have increased over time. The leopard attacks show a significant increase (R2=0.742, P<0.05) while the black bear attacks have increased slightly over the years (Figure 2, Table 2).

Table 2. Regression of the number of leopard and black bear attacks with the years (2014-2022).

Human Casualties

Black bear attacks were more prevalent on humans than on livestock. A total of eleven bear attacks were reported during the time frame on humans, further classified into severe injuries (N=7) and minor injuries (N=4). However, no human fatalities have been attributed to bear attacks. Leopard attacks on human resulted in minor injuries (N=4) and one death. In the present study, it was observed that humans were more prone to attacks by black bears rather than by leopards in the study area.

Forest Division-wise Human-Carnivore Conflict Incidences

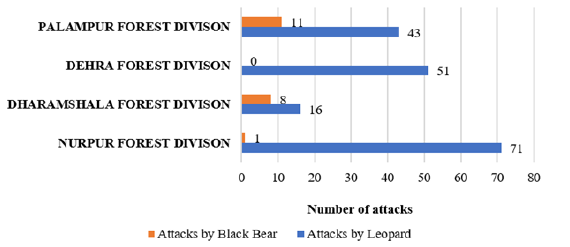

The highest number of reported attacks (N=72) was recorded in the Nurpur FD, where 421 livestock deaths occurred. This was followed by the Palampur FD (N=54) with 116 livestock deaths; Dehra FD, and Dharamshala FD reported N=51 and N=24 attacks, respectively (Figure 3). Among human casualties, the Nurpur FD recorded one fatal leopard attack, while the Dehra FD and Palampur FD reported one and two cases of minor injuries, respectively. Some cases of livestock depredation were also reported among migratory livestock, as pastoralists used the Nurpur region as a migratory route to the Chamba district (Supplementary Figure S3) during the summer months. Notably, in Dehra FD, all recorded HCC cases involved leopards, whereas in the Nurpur FD, Palampur FD, and Dharamshala FD, both leopards and black bears were responsible for conflicts.

Seasonal Trends in Human-Carnivore Conflict

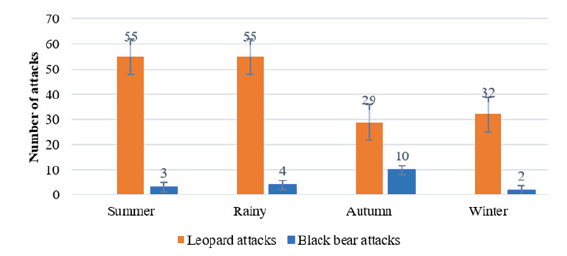

The number of reported HCC incidents increased from 15 cases in 2014 to a peak of 34 cases in 2020 (Figure 2). The highest number of attacks by both large carnivores was recorded in 2020, after which the cases declined in 2021 and remained lower until August 2022 (Figure 2). There was a significant difference in the seasonal pattern of the number of attacks (χ2=13.4234, df=3, P=0.0038). Seasonal analysis revealed that the highest number of attacks (N=59) occurred during the rainy season (July–September), followed by the summer season (March–June) with 58 reported incidents. Winter (December–February) and autumn (October–November) recorded 34 and 39 cases, respectively (Figure 4). The month of November had the highest number of reported cases (Supplementary Figure S1). Leopards exhibited the highest depredation rates during the summer (N=55) and rainy (N=55) seasons, followed by winter (N=32) and autumn (N=29). Conversely, black bears were most active during autumn (N=10), followed by the rainy season (N=4), summer (N=3), and winter (N=2).

Figure 2. The trend in the yearly numbers of leopard and black bear attacks from 2014 to 2022 in Kangra district.

Figure 3. The distribution of leopard and black bear attacks on livestock during the year 2014-August 2022 across forest divisions in Kangra district, Himachal Pradesh.

Compensation paid against incidences of HCC:

The Indian government uses ex-gratia payments as a policy measure to compensate individuals affected by HWC. State governments determine payments on a per-incident basis. Monetary compensation for the loss of lives and livelihoods is a major tool used by the government for reducing HCC. The compensation rates of the state have increased over time, with the revised list having nearly double the compensation rates (Supplementary Table S2). The forest department paid a total of 25,90,583/- rupees in compensation for leopard and black bear attacks reported to four divisional offices between January 2014

Figure 4. The seasonal pattern of attacks by leopard and black bear in the Kangra district during 2014-August 2022.

and August 2022. Black bear conflicts costed 6,74,102/- rupees, whereas leopard conflicts accounted costed 19,16,481/- rupees in compensation.

The revised rates reflect an effort to adjust for inflation over time, matching the rising costs of living, medical care, and livestock values. Compensation for human death increased from 1.5 lakh in 2014 to 4 lakh rupees in 2018, a substantial increase aimed to support the affected families. Also, the payments for permanent disability were doubled. The livestock categories like goat and sheep saw significant upward revisions, with rates tripled for large animals like horses, mules, buffaloes, and camels. Overall, these revisions acknowledge that static rates lose their adequacy over time due to inflation. Without revision, families affected by human–wildlife conflict would face an even heavier burden as medical treatment and replacement costs rise. However, some gaps remain. For instance, the compensation rate for grievous injuries remained unchanged, even though healthcare costs have risen steadily. This underlines the need for regular, comprehensive reviews of compensation policies to ensure that support provided to affected communities remains meaningful in real terms.

During in-person interviews with local inhabitants, it was found that though the compensation policies exist, there is a lack of awareness among people. It was also observed that even when people were aware of such policies, they usually refrained from applying for compensation, as the procedure and the additional associated costs involved were sometimes higher than the compensation received. Some respondents refrained due to past experiences of delay in receiving compensation. Based on our analysis, we suggest that continuous awareness programs regarding the application procedure and benefits of applying for compensation should be conducted in the villages closer to the forested area or high-conflict zones to encourage locals to apply for compensation. Ensuring timely reimbursement of compensation will improve public trust in the compensation scheme. These efforts will be effective in changing people’s perception of the compensation schemes and promoting reporting of conflict cases.

Limitations

Despite providing valuable insights, this study has certain limitations:

- Data Constraints – The study relied on departmental records from four forest divisions and a limited number of resident interviews. Incomplete official records or underreporting by affected individuals could have led to an underestimation of conflict cases.

- Potential Biases – Response bias in interviews, where participants may provide socially desirable answers, might have influenced the findings.

- Unaccounted Conflict Cases – Attacks on dogs were frequently mentioned during interviews, but were not included in the study, as compensation schemes do not cover them. This suggests that the actual level of HC may be higher than reported.

Conclusion

The present study examined the extent and patterns of human–carnivore conflict (HCC) in the Kangra district of Himachal Pradesh. Leopards and black bears are widely distributed across the state (Sharma, 2024 a & b), and both species are frequently involved in conflicts with humans. However, this study revealed a pronounced disparity in conflict frequency, with leopards accounting for 90.05% of reported cases, while black bears contributed only 9.95%. This difference may be attributed to the leopards’ wider distribution and their greater spatial overlap with human settlements and livestock, resulting in more frequent encounters (Charoo et al., 2011). On the contrary, a low bear conflict rate may reflect their more localized distribution and differing foraging preferences. Apart from the livestock and human attacks, crop depredation is the most common type of human-bear interaction reported (Charoo et al., 2011; Rawal et al., 2024). Seasonal variations also influenced the conflict patterns. Leopard depredation was highest during summer and monsoon months, while black bear attacks peaked in autumn, particularly during October and November. This seasonal increase in bear-related incidents coincides with their pre-hibernation foraging period when they actively search for food in upper-altitude regions (Bashir et al., 2018). These findings align partially with previous studies; for instance, Naha et al. (2018) reported peak leopard attacks in Pauri Garhwal between March and July, indicating regional differences possibly driven by local ecological and climatic factors. We reported spatial variation in conflict intensity across forest divisions. The Nurpur and Palampur FD recorded the highest number of leopard attacks, likely due to their connectivity with neighboring conflict-prone regions such as Chamba, Hamirpur, and Mandi Districts (Kumar & Chauhan, 2011; Athreya, 2015). Such landscape connectivity enables leopards to move freely across administrative boundaries, contributing to the persistence of conflicts. Livestock rearing—particularly of goats, sheep, and cattle—forms the backbone of the local economy, especially among the Gaddi community (Hill, 2021). However, a steady decline in livestock numbers between 1997 and 2019, coupled with increasing predator attacks, has intensified socio-economic challenges in the region (Sharma et al., 2022). It is important to note that the present study primarily relied on conflict cases reported by local residents, excluding data from migratory pastoralists, which may limit the completeness of conflict estimates. Future research should focus on understanding the migratory patterns of pastoralist communities and their livestock to identify specific risks associated with seasonal movement. In addition, integrating community-based conservation strategies—such as improved compensation schemes, livestock insurance, and the use of predator deterrents—could play a vital role in reducing conflicts. Effective management of human–wildlife conflict in Kangra will require an approach that simultaneously considers ecological, spatial, and socio-economic dimensions to promote coexistence and long-term conservation outcomes.

Recommendations

The increasing trend in HCC, particularly with leopards, highlights the need for proactive management strategies. Strengthening compensation mechanisms, implementing community-based mitigation measures, and further research on pastoralist vulnerabilities could help reduce conflicts. Future studies should also consider larger sample sizes and alternative data sources, such as camera traps and GPS tracking, to improve conflict documentation. HCC varies across different spatial and temporal scales, making it impractical to adopt a single, universal mitigation strategy. Therefore, location-specific and species-specific measures must be developed to enhance conflict management efforts. A multi-pronged approach integrating habitat conservation, livestock protection, and community involvement is essential for long-term conflict mitigation. Future research should also focus on developing sustainable coexistence models for human and wildlife populations.

TO DOWNLOAD SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL, CLICK HERE.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful to the staff of the respective Divisional Forest Offices, Himachal Pradesh for helping us obtain reliable information for this investigation. Moreover, we are grateful to the locals of the region for sharing conflict-related information during the interviews. We are also grateful to the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research for providing a Research fellowship to the first author. We are also thankful to the administration of the Central University of Jammu for providing the necessary administrative and laboratory support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed to the study design. Data collection and analysis were performed by NM. The idea was convinced by both authors (NM, VS). The first draft of the manuscript was written by NM. VS suggested the necessary modification in the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Edited By

Tapajit Bhattacharya

Durgapur Government College, Paschim Bardhaman, India.

*CORRESPONDENCE

Vinita Sharma

✉ vinita302003@gmail.com

CITATION

Mehra, N. & Sharma, V. (2025). Human-Carnivore Conflict: A cause of concern for District Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India. Journal of Wildlife Science, 2(4), 127-132. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.DJEZ4982

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Mehra & Sharma. This is an open-access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The information contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Athreya, Vidya (2015). Study of human leopard conflict in Himachal Pradesh. An interim report-Wildlife Conservation Society-India and Wildlife Wing, Forest Department, Government of Himachal Pradesh.

Bashir, T., Bhattacharya, T., Poudyal, K., Qureshi, Q. & Sathyakumar, S. (2018). Understanding patterns of distribution and space-use by Ursus thibetanus in Khangchendzonga, India: Initiative towards conservation. Mammalian Biology, 92(1), 11-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2018.04.004

Bhardwaj, S., Thakur, S., Singh, A. P. & De, K. (2024). Livestock Depredation Pattern by Common Leopard: A Case Study from Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area. National Academy Science Letters, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40009-024-01470-9

Bryhn, A. C. & Dimberg, P. H. (2011). An operational definition of a statistically meaningful trend. PLoS One, 6(4), e19241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019241

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India (2011). Census of India 2011: A-01: Number of villages, towns, households, population and area (India, states/UTs, districts and Sub-districts) - 2011. Census of India. Census tables | Government of India [Access on 29/09/2023]

Charoo, S. A., Sharma, L. K. & Sathyakumar, S. (2011). Asiatic black bear–human interactions around Dachigam National Park, Kashmir, India. Ursus, 22(2), 106-113. https://doi.org/10.2307/41304062

Chauhan, N. P. S. & Rajpurohit, K. S. (1996). Study of animal damage problems in and around protected areas and managed forest in India Phase I: Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Orissa. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.

Chauhan, N. P. S., Kavita, A. & Kamboj, N. (2002). Leopard–Human Conflicts in Pauri, Thailisen, Chamoli and Pithoragarh: Project Report. Dehradun, India: Wildlife Institute of India.

Das, C. S. (2018). Pattern and characterisation of human casualties in Sundarban by Tiger attacks, India. Sustainable Forestry, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.24294/sf.v1i2.873

Distefano, E. (2005). Human-Wildlife Conflict worldwide: collection of case studies, analysis of management strategies and good practices. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development Initiative (SARDI), Rome, Italy. Available from: FAO Corporate Document repository. http://www.fao.org/documents

Gemeda, D. O. & Meles, S. K. (2018). Impacts of human-wildlife conflict in developing countries. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 22(8), 1233-1238. https://doi.org/10.4314/jasem.v22i8.14

Hill, C. M. (2021). Conflict is Integral to Human-Wildlife Coexistence. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 2, 734314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.734314

Forest Survey of India (2021). India State of Forest Report 2021. Forest Survey of India (Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change), Kaulagarh Road, Dehradun, India. ISBN 978-81-950073-1-8

Kichloo, M. A., Sohil, A. & Sharma, N. (2024). Living with leopards: an assessment of conflict and people's attitudes towards the common leopard Panthera pardus in a protected area in the Indian Himalayan region. Oryx, 58(2), 202-209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605323001278

Kumar, D. & Chauhan, N. P. S. (2011). Human-leopard conflict in Mandi district, Himachal Pradesh, India. Julius-Kühn-Archiv, (432), 180.

Madhusudan, M. D. (2003). Living Amidst Large Wildlife: Livestock and Crop Depredation by Large Mammals in the Interior Villages of Bhadra Tiger Reserve, South India. Environmental Management, 31(4), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-002-2790-8

Mahajan (2020). Human-wildlife conflict on rise in Himachal Pradesh. The pioneer. https://www.dailypioneer.com/2020/state-editions/human-wildlife-conflict-on-rise-in-himachal-pradesh.html

Mohanta, R. & Chauhan, N. P. S. (2014). Anthropogenic threats and its conservation on Himalayan Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) habitat in Kugti wildlife sanctuary, Himachal Pradesh, India. Asian Journal of Conservation Biology, 3(2), 175-180.

Naha, D., Sathyakumar, S. & Rawat, G. S. (2018). Understanding drivers of human-leopard conflicts in the Indian Himalayan region: spatio-temporal patterns of conflicts and perception of local communities towards conserving large carnivores. Plos one, 13(10), e0204528. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204528

QGIS.org (2021). QGIS Geographic Information System. Open-Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.org

Rathore, B. C. & Chauhan, N. P. S. (2014). The food habits of the Himalayan Brown Bear Ursus arctos (Mammalia: Carnivora: Ursidae) in Kugti Wildlife Sanctuary, Himachal Pradesh, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 6(14), 6649-6658. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o3609.6649-58

Rawal, A. K., Timilsina, S., Gautam, S., Lamichhane, S. & Adhikari, H. (2024). Asiatic black Bear–Human conflict: A case study from Guthichaur rural municipality, Jumla, Nepal. Animals, 14(8), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14081206

Sharma, A., Parkash, O. & Uniyal, S. K. (2022). Moving away from transhumance: The case of Gaddis. Trees, Forests and People, 7, 100193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2022.100193

Sharma, L. K. (2024a). Population estimation and assessment of human-wildlife conflicts for conservation and management planning of Common Leopard and Asiatic Black bear in Himachal Pradesh. p.61.

Sharma, L. K. (2024b). Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Baseline Survey and development of comprehensive strategy for its mitigation in selected district of Himachal Pradesh, Final Technical Report, Zoological Survey of India and Himachal Pradesh Forest Department. p.127

Sharma, M., Thakur, D. & Thakur, A. (2022). Dynamics of livestock population in Himachal Pradesh. Indian Journal of Dairy Science, 75(1). https://doi.org/10.33785/IJDS.2022.v75i01.015

Sharma, P., Chettri, N. & Wangchuk, K. (2021). Human–wildlife conflict in the roof of the world: Understanding multidimensional perspectives through a systematic review. Ecology and evolution, 11(17), 11569-11586. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7980

Sharma, R. K., Gupta, A., Singh, R. Sripal, R., Nagpal, T., Rajendran, T. (2020). Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Strategy in Pangi, Lahaul, and Kinnaur Landscapes, Himachal Pradesh. GEF-GoI-UNDP SECURE Himalaya Project.

Suryawanshi, K. R., Bhatnagar, Y. V., Redpath, S. & Mishra, C. (2013). People, predators and perceptions: patterns of livestock depredation by snow leopards and wolves. Journal of Applied Ecology, 50(3), 550-560. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12061

Edited By

Tapajit Bhattacharya

Durgapur Government College, Paschim Bardhaman, India.

*CORRESPONDENCE

Vinita Sharma

✉ vinita302003@gmail.com

CITATION

Mehra, N. & Sharma, V. (2025). Human-Carnivore Conflict: A cause of concern for District Kangra, Himachal Pradesh, India. Journal of Wildlife Science, 2(4), 127-132. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.DJEZ4982

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Mehra & Sharma. This is an open-access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The information contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Athreya, Vidya (2015). Study of human leopard conflict in Himachal Pradesh. An interim report-Wildlife Conservation Society-India and Wildlife Wing, Forest Department, Government of Himachal Pradesh.

Bashir, T., Bhattacharya, T., Poudyal, K., Qureshi, Q. & Sathyakumar, S. (2018). Understanding patterns of distribution and space-use by Ursus thibetanus in Khangchendzonga, India: Initiative towards conservation. Mammalian Biology, 92(1), 11-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mambio.2018.04.004

Bhardwaj, S., Thakur, S., Singh, A. P. & De, K. (2024). Livestock Depredation Pattern by Common Leopard: A Case Study from Great Himalayan National Park Conservation Area. National Academy Science Letters, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40009-024-01470-9

Bryhn, A. C. & Dimberg, P. H. (2011). An operational definition of a statistically meaningful trend. PLoS One, 6(4), e19241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019241

Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India (2011). Census of India 2011: A-01: Number of villages, towns, households, population and area (India, states/UTs, districts and Sub-districts) - 2011. Census of India. Census tables | Government of India [Access on 29/09/2023]

Charoo, S. A., Sharma, L. K. & Sathyakumar, S. (2011). Asiatic black bear–human interactions around Dachigam National Park, Kashmir, India. Ursus, 22(2), 106-113. https://doi.org/10.2307/41304062

Chauhan, N. P. S. & Rajpurohit, K. S. (1996). Study of animal damage problems in and around protected areas and managed forest in India Phase I: Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Orissa. Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, India.

Chauhan, N. P. S., Kavita, A. & Kamboj, N. (2002). Leopard–Human Conflicts in Pauri, Thailisen, Chamoli and Pithoragarh: Project Report. Dehradun, India: Wildlife Institute of India.

Das, C. S. (2018). Pattern and characterisation of human casualties in Sundarban by Tiger attacks, India. Sustainable Forestry, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.24294/sf.v1i2.873

Distefano, E. (2005). Human-Wildlife Conflict worldwide: collection of case studies, analysis of management strategies and good practices. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development Initiative (SARDI), Rome, Italy. Available from: FAO Corporate Document repository. http://www.fao.org/documents

Gemeda, D. O. & Meles, S. K. (2018). Impacts of human-wildlife conflict in developing countries. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 22(8), 1233-1238. https://doi.org/10.4314/jasem.v22i8.14

Hill, C. M. (2021). Conflict is Integral to Human-Wildlife Coexistence. Frontiers in Conservation Science, 2, 734314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcosc.2021.734314

Forest Survey of India (2021). India State of Forest Report 2021. Forest Survey of India (Ministry of Environment Forest and Climate Change), Kaulagarh Road, Dehradun, India. ISBN 978-81-950073-1-8

Kichloo, M. A., Sohil, A. & Sharma, N. (2024). Living with leopards: an assessment of conflict and people's attitudes towards the common leopard Panthera pardus in a protected area in the Indian Himalayan region. Oryx, 58(2), 202-209. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605323001278

Kumar, D. & Chauhan, N. P. S. (2011). Human-leopard conflict in Mandi district, Himachal Pradesh, India. Julius-Kühn-Archiv, (432), 180.

Madhusudan, M. D. (2003). Living Amidst Large Wildlife: Livestock and Crop Depredation by Large Mammals in the Interior Villages of Bhadra Tiger Reserve, South India. Environmental Management, 31(4), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-002-2790-8

Mahajan (2020). Human-wildlife conflict on rise in Himachal Pradesh. The pioneer. https://www.dailypioneer.com/2020/state-editions/human-wildlife-conflict-on-rise-in-himachal-pradesh.html

Mohanta, R. & Chauhan, N. P. S. (2014). Anthropogenic threats and its conservation on Himalayan Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) habitat in Kugti wildlife sanctuary, Himachal Pradesh, India. Asian Journal of Conservation Biology, 3(2), 175-180.

Naha, D., Sathyakumar, S. & Rawat, G. S. (2018). Understanding drivers of human-leopard conflicts in the Indian Himalayan region: spatio-temporal patterns of conflicts and perception of local communities towards conserving large carnivores. Plos one, 13(10), e0204528. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204528

QGIS.org (2021). QGIS Geographic Information System. Open-Source Geospatial Foundation Project. http://qgis.org

Rathore, B. C. & Chauhan, N. P. S. (2014). The food habits of the Himalayan Brown Bear Ursus arctos (Mammalia: Carnivora: Ursidae) in Kugti Wildlife Sanctuary, Himachal Pradesh, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 6(14), 6649-6658. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o3609.6649-58

Rawal, A. K., Timilsina, S., Gautam, S., Lamichhane, S. & Adhikari, H. (2024). Asiatic black Bear–Human conflict: A case study from Guthichaur rural municipality, Jumla, Nepal. Animals, 14(8), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14081206

Sharma, A., Parkash, O. & Uniyal, S. K. (2022). Moving away from transhumance: The case of Gaddis. Trees, Forests and People, 7, 100193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2022.100193

Sharma, L. K. (2024a). Population estimation and assessment of human-wildlife conflicts for conservation and management planning of Common Leopard and Asiatic Black bear in Himachal Pradesh. p.61.

Sharma, L. K. (2024b). Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Baseline Survey and development of comprehensive strategy for its mitigation in selected district of Himachal Pradesh, Final Technical Report, Zoological Survey of India and Himachal Pradesh Forest Department. p.127

Sharma, M., Thakur, D. & Thakur, A. (2022). Dynamics of livestock population in Himachal Pradesh. Indian Journal of Dairy Science, 75(1). https://doi.org/10.33785/IJDS.2022.v75i01.015

Sharma, P., Chettri, N. & Wangchuk, K. (2021). Human–wildlife conflict in the roof of the world: Understanding multidimensional perspectives through a systematic review. Ecology and evolution, 11(17), 11569-11586. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7980

Sharma, R. K., Gupta, A., Singh, R. Sripal, R., Nagpal, T., Rajendran, T. (2020). Human-Wildlife Conflict Management Strategy in Pangi, Lahaul, and Kinnaur Landscapes, Himachal Pradesh. GEF-GoI-UNDP SECURE Himalaya Project.

Suryawanshi, K. R., Bhatnagar, Y. V., Redpath, S. & Mishra, C. (2013). People, predators and perceptions: patterns of livestock depredation by snow leopards and wolves. Journal of Applied Ecology, 50(3), 550-560. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12061