TYPE: Natural History Note![]()

Nest-site Selection and Adaptability of the Asian Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Human-dominated Landscapes of Kerala, India

RECEIVED 19 July 2025

ACCEPTED 24 November 2025

ONLINE EARLY 02 January 2026

Abstract

The Asian Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus), a Near Threatened species, is increasingly observed breeding in human-dominated landscapes across South Asia. However, systematic studies on its nesting ecology in India remain scarce. This study investigates nest-site selection and adaptability of C. episcopus in the rapidly transforming landscapes of central Kerala, India. We recorded 30 active nests during the 2022 and 2023 breeding seasons across four districts, using a combination of citizen science data, field surveys, and spatial analyses. Nests were found on both natural (53.3%) and artificial substrates (46.7%), including trees and man-made structures such as telecom towers and electric pylons. Nesting sites were typically located near agricultural wetlands, rivers, and human settlements, with many nests situated within 5 km of major rivers and within 50 m of buildings or roads. Despite high levels of anthropogenic disturbance, storks demonstrated strong adaptability in substrate use, height preferences, and spatial proximity to foraging habitats. Our findings highlight the species’ behavioral flexibility and its reliance on wetland– agriculture mosaics in modified environments. This study highlights the species’ persistence in modified habitats and underscores the need to integrate wetland and nest-site protection into regional conservation planning.

Keywords: Anthropogenic landscapes, breeding ecology, nest-site selection, urban ecology, wetland–agriculture mosaic.

Introduction

The Asian Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) is a large, solitary species found across South and Southeast Asia. It occupies a broad range of habitats, including grasslands, wetlands, agricultural fields (both dry and flooded), reservoirs, irrigation canals, and forest openings (Mlodinow et al., 2022). In India, the species increasingly occupies human-dominated landscapes such as farmlands and peri-urban zones, suggesting behavioral flexibility and adaptability to altered ecosystems (Ghimire et al., 2021; Kittur & Sundar, 2021; Ghimire et al., 2021). Although globally listed as Near Threatened, regional populations face mounting pressures from habitat loss and land-use change (BirdLife International, 2022; SoIB, 2023).

Nest-site selection plays a critical role in the reproductive success of storks and is influenced by substrate type, foraging proximity, and disturbance levels (Onmuş et al., 2012; Tobolka et al., 2013). While many large waterbirds favor secluded wetland habitats, Woolly-necked Storks frequently nest in anthropogenic environments, including agroforestry trees, electric pylons, and mobile telecom towers (Thabethe & Downs, 2018; Kittur & Sundar, 2021). In India and Nepal, the species shows a strong association with irrigation canals, bunds, and rice landscapes, indicating its capacity to exploit mixed-use areas for nesting and foraging (Ghimire et al., 2020; Hasan & Ghimire, 2020).

Kerala, located in the southwestern coastal zone of India, is part of the Western Ghats biodiversity hotspot and is characterized by high species richness and endemism. However, the region is undergoing rapid land-use change, with extensive agricultural intensification, urban sprawl, and infrastructure development affecting wetland and riverine ecosystems (Krishna et al., 2024). Understanding how adaptable species like the C. episcopus navigate these changes is crucial for biodiversity conservation planning in such dynamic landscapes.

In Kerala, breeding records of C. episcopus are limited, with the earliest documented nest from the Periyar Tiger Reserve (Neelakantan, 2004). However, more recent observations and citizen science reports suggest a possible expansion of the breeding range in the state, concentrating in Malappuram, Thrissur, and Palakkad districts of Central Kerala (Roshnath & Greeshma, 2020). Despite these developments, systematic studies on the species’ nesting ecology in Kerala remain lacking.

In this study, we examined the nest-site characteristics of C. episcopus in central Kerala. Specifically, we (1) compared nesting on trees versus artificial structures, (2) quantified spatial relationships with wetlands and rivers, and (3) assessed proximity to human disturbance. These insights contribute to understanding how large waterbirds persist in increasingly modified tropical landscapes.

Material and methods

Nesting sites of C. episcopus in Kerala were identified through a combination of secondary data and systematic field surveys. Initial locations were compiled from published literature (Sashikumar et al., 2011; Greeshma et al., 2018; Roshnath & Greeshma, 2020), citizen science observations from eBird from 2014 to 2020 (www.ebird.org), having reports of confirmed breeding behavior, such as nest-building, occupied nests, and nests containing eggs or chicks. Field inspections were carried out to verify these reports and to assess the nesting status. Additional nesting records were gathered through outreach to local birdwatchers and appeals posted on birding forums and WhatsApp groups, and an inventory of known nesting sites was prepared.

Fieldwork was conducted during the post-monsoon breeding seasons (Sept to Dec) of 2022 and 2023, focusing on three central districts in Kerala known to support breeding populations (Roshnath & Greeshma 2020). A stratified random sampling design was applied using a 5 × 5 km grid system created in ArcGIS 10.7. Of 400 total grids, 15% were randomly selected for surveys, excluding areas under forest cover. Each selected grid was systematically surveyed on foot and by vehicle to detect active nests and to identify any potential nesting sites not included in the existing inventory.

At each nest site, we recorded tree and site-level variables. For natural substrates (trees), we measured tree height and nest height using a HAWKE LRF 400 laser rangefinder. Girth at breast height (GBH), canopy length (L), and canopy breadth (B) were measured using a 30 m fiberglass tape. Canopy spread was calculated as (L + B)/2 (Blozan 2006). For all sites, we recorded the distance to the nearest wetland, river, and water body (e.g., bund or check dam), as well as anthropogenic features such as roads, buildings, and settlements. These distances were measured using high-resolution satellite imagery in Google Earth Pro.

Wetlands were defined following the Ramsar convention (1971) to include marshes, fens, bogs, and all bodies of water-natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with static or flowing water. Given the importance of rice fields as nesting and foraging habitats for storks (Sundar & Subramanya, 2010), these were also included under wetlands. Similarly, major water bodies, including dams, check dams, and bunds across rivers or stagnant water, were identified, as these often retain significant water volumes during summer and serve as key foraging areas. Roads were defined as pathways wider than 5 meters with moderate vehicle or pedestrian traffic. Buildings were categorized as permanent, enclosed man-made structures (e.g., residences, commercial establishments, or public infrastructure). Human settlements were defined as populated clusters consisting of five or more buildings or houses in close proximity.

Results

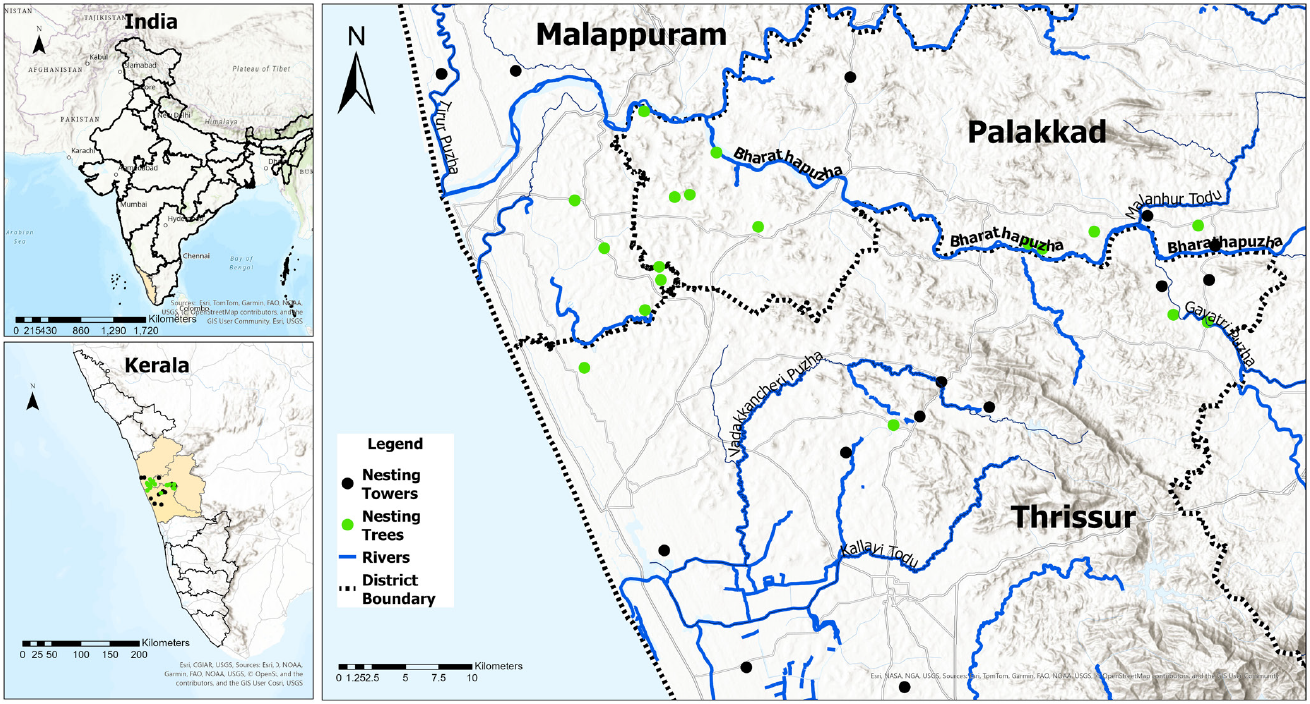

A total of 30 active nests of Ciconia episcopus were recorded in Kerala during the 2022 and 2023 breeding seasons (Fig. 1). Thrissur district supported the highest number of nests (n = 14), followed by Palakkad (n = 9), Malappuram (n = 6), and Idukki (n = 1; Table 1).

Table 1: District-wise distribution of Asian Woolly-necked Stork nesting substrates in Kerala, India. Nesting sites were recorded on tree species and anthropogenic structures across Malappuram, Palakkad, Thrissur, and Idukki districts, with telecom towers constituting the most frequently used substrate.

Nesting sites were located at a mean elevation of 28 ± 24 m. Nests were frequently situated near aquatic habitats, including wetlands or paddy fields (mean distance = 237 ± 170.8 m), rivers (2512.5 ± 4472.3 m), and stagnant water bodies such as check dams or bunds (3037.1 ± 1990.0 m). A majority of nests (n = 22) were located within 5 km of a major river. Specifically, 12 nests were found within 1 km, 4 nests between 1–3 km, and 6 nests between 3–5 km from the nearest riverbank.

Despite proximity to human infrastructure, nesting did not appear to be negatively impacted by anthropogenic disturbance. Nests were recorded near buildings (mean distance = 8.4 ± 8.6 m), roads (12.0 ± 20.0 m), and human settlements (50.0 ± 49.5 m), suggesting tolerance of or adaptation to human-modified landscapes.

Storks nested both on trees (n = 16, 53.3%) and artificial structures such as telecom and electric towers (n = 14, 46.7%; Table 2). Tree species commonly used for nesting included Alstonia scholaris, Ficus benghalensis, Mangifera indica, and Terminalia elliptica (Table 1). Nesting trees had a mean height of 19.6 ± 3.7 m, girth at breast height (GBH) of 3.7 ± 3.8 m, and canopy spread of 9.5 ± 10.3 m. Towers used as nest substrates had a significantly greater mean height of 35.1 ± 9.0 m (t = 5.107, df = 11.38, p < 0.005), and a strong positive correlation was observed between nest height and total substrate height (Pearson’s R = 0.86).

Discussion

C. episcopus are considered local migrants in Kerala, with a widespread presence during the winter and a relatively small breeding population (Roshnath & Greeshma, 2020). Similar patterns have been noted in African populations, where year-round residency is increasingly observed in urban and peri-urban areas, driven by supplemental feeding and anthropogenic resource availability (Thabethe & Downs, 2018).

Figure 1. Study area showing the spatial distribution of Asian Woolly-necked Stork nesting sites in central Kerala, India. Black circles indicate nests on telecom towers, green circles indicate nests on trees.

In the present study, 30 active nesting sites were recorded through systematic surveys across central Kerala, an increase from earlier reports of 10 nests (Greeshma et al., 2018) and 16 nests (Roshnath & Greeshma, 2020). This rise may be attributed to more extensive field efforts, growing citizen science participation, and potentially an ecological shift toward increased residency, possibly facilitated by favorable breeding and foraging conditions in agricultural and semi-urban landscapes.

Central Kerala supports nearly all known nesting locations of C. episcopus in the state, except for the nesting site in Periyar Tiger Reserve. C. episcopus feeds on a broad range of prey, including invertebrates, reptiles, mollusks, crabs, insects, fish, frogs, toads, and snakes, many of which are abundant along riverbeds and sandbanks (del Hoyo et al., 2020). The Bharathapuzha river basin, characterized by its exposed riverbeds and sandy banks, may thus serve as an important foraging and nesting area for the species (Sashikumar et al., 2011). Most recorded nests in this study were located near Bharathapuzha or its tributaries, including the Gayathripuzha, Puzhakkal, and Karuvannur rivers. These river basins cover Palakkad, Thrissur, and Malappuram districts of Kerala. Most nests were located within agricultural landscapes or near water bodies such as check dams and bunds, reflecting their preference for hydrologically rich environments. Similar nesting patterns have been observed in other regions across South Asia (Banerjee, 2017; Ghimire et al., 2020; Hasan & Ghimire, 2020; Katuwal et al., 2020; Mehta, 2020; Sundar, 2020; Kittur & Sundar, 2021). Of the 30 nests recorded, 22 were within 5 km of a major river, aligning with earlier studies that highlight rivers as key foraging habitats for this species (Rahmani & Singh, 1996; Vyas & Tomar, 2007; Vaghela et al., 2015; Hasan & Ghimire, 2020). For storks, minimizing travel distance to foraging areas can reduce energy expenditure and potentially increase reproductive success (Alonso et al., 1991; Gibert et al., 2016). These findings emphasize the importance of wetland–agriculture mosaics as critical habitats for the C. episcopus breeding and foraging needs.

The region encompasses the Kole lands, a major rice-growing landscape of Kerala, and forms part of the Vembanad–Kole wetland system (151,250 ha), which has beenwas designated as a Ramsar site in 2002 (Srinivasan, 2010). C. episcopus were often seen nesting on trees near irrigation canals, showing their close link with farming landscapes (Kittur & Sundar, 2021). These agricultural and wetland-rich areas of central Kerala likely offer a combination of suitable nesting substrates, food availability, and human tolerance, explaining the localized breeding distribution of the species in the region.

Storks exhibit strong morphological and behavioral adaptations to wetland habitats. Their long legs and bills facilitate efficient foraging in shallow waters, allowing them to exploit a wide range of aquatic prey (Hancock et al., 1992; Mlodinow et al., 2022). Nesting close to wetlands, rivers, and irrigation structures provides easy access to food, supporting their breeding ecology.

Our study found that C. episcopus frequently nests in close proximity to human infrastructure, with several nests located directly atop towers built on buildings, and others situated very near roads and human settlements. This pattern suggests a strong habituation to human presence. Such tolerance has been identified as a key trait enabling waterbirds to persist in urbanized environments (Charutha et al., 2021). C. episcopus have previously been reported breeding in human-dominated landscapes, including farmlands, towns, and urban peripheries (Kittur & Sundar, 2021), and highly urban areas (Kularatne & Udagedara, 2017). Nesting near roads may help avoid natural predators (Rao & Koli, 2017) and offer structural safety (Leveau & Leveau, 2005; Pescador & Peris, 2007). Our results reinforce these observations, emphasizing the species’ adaptability and behavioral flexibility in selecting nest sites in highly modified landscapes (Thabethe, 2018; Ghimire et al., 2021). This capacity to tolerate or even benefit from anthropogenic environments may play a crucial role in the continued persistence of small breeding populations in human-dominated regions like central Kerala.

Birds that are habituated to human presence can exploit anthropogenic resources for both breeding and foraging, thereby enhancing their ability to persist and even thrive in urban landscapes (Møller, 2009; Sullivan et al., 2015). In India, urban waterbird colonies frequently utilize man-made structures and large trees in city environments for nesting (Mehta et al., 2024; Roshnath & Sinu, 2017). C. episcopus in particular has been observed nesting on telecom towers and electric pylons, a trend documented across multiple regions in India (Kittur & Sundar, 2021) and also in African populations (Thabethe, 2018). In our study, 13 nests were located on telecom towers and one on an electric tower, underscoring the species’ capacity to adapt to artificial structures in human-dominated landscapes.

C. episcopus generally prefer nesting in trees with dense foliage, selecting middle canopy layers where thick, horizontal lateral branches are typically fewer in number and located away from the main trunk, which offer both concealment and protection from climbing predators by providing stable platforms for nest placement (Ishtiaq et al., 2004; Thabethe, 2018). In our study, most tree nests were similarly placed on lateral branches, consistent with prior observations; for artificial substrates, the nest on an electric transmission tower was constructed in a corner where intersecting iron beams provided a stable base, while nests on mobile towers were typically located on the highest accessible flat platforms indicating a preference for structurally stable sites akin to those selected in natural nesting substrates.

Storks tend to nest at elevated heights to reduce the risk of predation from terrestrial mammals (Vaitkuviene & Dagys, 2015), often selecting taller and broader trees compared to surrounding trees (Ghimire et al., 2022); similarly, the preference for nesting on taller towers over shorter trees, as noted in previous studies (Vaghela et al., 2015), suggests that height is likely a key factor influencing nest site selection. Although this behavior may contribute to short-term population stability, it raises concerns about long-term ecological consequences if infrastructural modifications or maintenance activities disrupt breeding, and such adaptability is not unique to Kerala. Across India and parts of Africa, C. episcopus have been documented nesting in highly modified environments, utilizing mobile towers, electric pylons, and large trees in human-dominated areas (Thabethe 2018; Kittur & Sundar, 2021).

The findings of this study emphasize the importance of wetland–agriculture mosaics and human tolerance of C. episcopus populations. With increasing urban sprawl and land-use conversion in Kerala (Krishna et al., 2024), conservation and urban planning policies must integrate the needs of adaptable but vulnerable species like C. episcopus. Protecting remnant wetlands, conserving tall agroforestry trees, regulating tower maintenance during the breeding season, and integrating biodiversity safeguards into rural development programs could greatly enhance nesting success and population resilience.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the members of the Malabar Awareness and Rescue Centre for Wildlife, Kannur and the staff of the Centre for Wildlife Studies, Kerala Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Wayanad, and for their continuous support throughout the study. We also extend our sincere thanks to the Kerala Forest and Wildlife Department, with special gratitude to Mr. D. Jayaprasad, IFS, for selecting the project for funding and for his consistent support provided during the study. We thank Divin V for helping in data analsysis and Shivachand MP for preparing map of the study area.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data is available from the corresponding author on request.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

R. Roshnath conceived and designed the study, supervised the research, analyzed data and revised the manuscript to its final form. U.K. Amal and Naveen P. Mathew conducted the fieldwork, collected data, and prepared the initial draft of the manuscript.

Edited By

Upasana Ganguly

University of Louisiana at Lafayette, USA

*CORRESPONDENCE

Ramesh Roshnath

✉ roshnath.r@gmail.com

Navin P. Mathew

✉ navinpmathew@gmail.com

SPECIAL ISSUE

This paper is published in the Special Issue ‘Master’s Dissertations’. It was M.S. dissertation work of Navin P. Mathew.

CITATION

Roshnath, R., Amal, U. K. & Mathew, N. P. (2025). Nest-site Selection and Adaptability of the Asian Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Human-dominated Landscapes of Kerala, India. Journal of Wildlife Science, Online Early Publication, 01-05 . https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.DBPL7531

FUNDING

This study was funded by the Kerala Forest and Wildlife Department, Government of Kerala to Ramesh Roshnath.

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Roshnath, Amal & Mathew. This is an open-access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The informa¬tion contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alonso, J. C., Alonso, J. A. & Carrascal, L. M. (1991). Habitat selection by foraging White Storks, Ciconia ciconia, during the breeding season. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69(7), 1957-1962. https://doi.org/10.1139/z91-270

Banerjee, P. (2017). The Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus re-using an old Grey Heron Ardea cinerea nest. Indian Birds, 13, 165.

BirdLife International. (2022). Species factsheet: Ciconia episcopus. Retrieved from http://www.birdlife.org (Accessed on 20 October 2024).

Blozan, W. (2006). Tree measuring guidelines of the Eastern Native Tree Society. Bulletin of the Eastern Native Tree Society, 1(1), 3–10.

Charutha, K., Roshnath, R. & Sinu, P. A. (2021). Urban heronry birds tolerate human presence more than its conspecific rural birds. Journal of Natural History, 55(9–10), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2021.1912844

del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Collar, N., Garcia, E. F. J., Boesman, P. F. D. & Kirwan, G. M. (2020). Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wonsto1.01

Ghimire, P., Ghimire, R., Low, M., Bist, B. S. & Pandey, N. (2021). The Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus: A review of its status, distribution and ecology. Ornithological Science, 20, 2. https://doi.org/10.2326/osj.20.223

Ghimire, P., Pandey, N., Belbase, B., Ghimire, R., Khanal, C., Bist, B. S. & Bhusal, K. P. (2020). If you go, I’ll stay: Nest use interaction between Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus and Black Kite Milvus migrans in Nepal. Birding Asia, 33, 103–105.

Ghimire, P., Panthi, S., Bhusal, K. P., Low, M., Pandey, N., Ghimire, R., Bist, B. S., Khanal, S. & Poudyal, L. P. (2022). Nesting habitat suitability and breeding of Asian Woollyneck (Ciconia episcopus) in Nepal. Ornithology Research, 30(4), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43388-022-00104-2

Gilbert, N. I., Correia, R. A., Silva, J. P., Pacheco, C., Catry, I., Atkinson, P. W., Gill, J. A. & Franco, A. M. (2016). Are white storks addicted to junk food? Impacts of landfill use on the movement and behaviour of resident White Storks (Ciconia ciconia) from a partially migratory population. Movement Ecology, 4, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-016-0070-0

Greeshma, P., Nair, R. P., Jayson, E. A., Manoj, K., Arya, V. & Shonith, E. G. (2018). Breeding of Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus in Bharathapuzha River Basin, Kerala, India. Indian Birds, 14(3), 86–87.

Hancock, J., Kushlan, J. & Kahl, M. P. (1992). Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World. Academic Press, London.

Hasan, M. & Ghimire, P. (2020). Confirmed breeding records of Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus from Bangladesh. SIS Conservation, 2, 47–49.

Ishtiaq, F., Rahmani, A. R., Javed, S. & Coulter, M. C. (2004). Nest-site characteristics of Black-necked Stork (Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus) and White-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 101, 90–95.

Katuwal, H. B., Baral, H. S., Sharma, H. P. & Quan, R. C. (2020). Asian Woollynecks are uncommon on the farmlands of lowland Nepal. SIS Conservation, 2, 50–54.

Kittur, S. & Sundar, K. G. (2021). Of irrigation canals and multifunctional agroforestry: Traditional agriculture facilitates Woolly-necked Stork breeding in a north Indian agricultural landscape. Global Ecology and Conservation, 30, e01793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01793

Krishna, N. G., Alam, S., Prakash, S., Yadav, K., Ahmad, S. & Ojha, A. (2024). Understanding the spatio-temporal variation of urbanisation in Kerala, India. GeoJournal, 89(4), 126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10869-0

Kularatne, H. & Udagedara, S. (2017). First record of the Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus Boddaert, 1783 (Aves: Ciconiiformes: Ciconiidae) breeding in the lowland wet zone of Sri Lanka. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 9, 9738–9742. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.2904.9.1.9738-9742

Leveau, C. M. & Leveau, L. M. (2005). Avian community response to urbanization in the Pampean region, Argentina. Ornitologia Neotropical, 16, 503–510.

Mehta, K. (2020). Observations of Woolly-necked Stork nesting attempts in Udaipur city, Rajasthan, India. SIS Conservation, 2, 68–70.

Mehta, K., Koli, V. K., Kittur, S. & Gopi Sundar, K. S. (2024). Can you nest where you roost? Waterbirds use different sites but similar cues to locate roosting and breeding sites in a small Indian city. Urban Ecosystems, 27(4), 1279–1290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-023-01454-5

Mlodinow, S. G., del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Collar, N., Garcia, E., Boesman, P. F. D. & Kirwan, G. M. (2022). Asian Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus), version 1.1. In Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wonsto1.01.1

Møller, A. P. (2009). Successful city dwellers: a comparative study of the ecological characteristics of urban birds in the Western Palearctic. Oecologia, 159, 849–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1259-8

Neelakantan, K. K. (2004). Keralathile Pakshikal. Kerala Sahitya Academy, Thrissur, Kerala, India, 570 pp.

Onmuş, O., Sıkı, M. & Kılıç, D. T. (2012). Nest site selection and reproductive success in a colony of White Storks (Ciconia ciconia) in western Turkey. Turkish Journal of Zoology, 36(4), 479–489.

Pescador, M. & Peris, S. (2007). Influence of roads on bird nest predation: An experimental study in the Iberian Peninsula. Landscape and Urban Planning, 82(1–2), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.01.017

Rahmani, A. R. & Singh, B. (1996). White-necked or Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus nesting on cliffs. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 93(2), 293–294.

Ramsar Convention Secretariat. (1971). The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat. Ramsar, Iran.

Rao, S. & Koli, V. K. (2017). Edge effect of busy high traffic roads on the nest site selection of birds inside the city area: Guild response. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 51, 94-101.

Roshnath, R. & Greeshma, C. (2020). Distribution records of Woolly-necked Storks in Kerala, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 12(8), 15800–15805.

Roshnath, R. & Sinu, P. A. (2017). Nesting tree characteristics of heronry birds of urban ecosystems in peninsular India: implications for habitat management. Current Zoology, 63(6), 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/cz/zox006

Sashikumar, C., Praveen, J., Palot, M. J. & Nameer, P. O. (2011). Birds of Kerala: Status and Distribution. DC Books, Kottayam, Kerala, India, p.835.

SoIB (2023). State of India's Birds factsheet: Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus (India). https://stateofindiasbirds.in/species/wonsto1/ (Accessed on 01 November 2025)

Srinivasan, J. T. (2010). Understanding the Kole Lands in Kerala as A Multiple Use Wetland Ecosystem. Hyderabad: Research Unit for Livelihoods and Natural Resources.

Sullivan, M. J., Davies, R. G., Mossman, H. L. & Franco, A. M. (2015). An Anthropogenic Habitat Facilitates the Establishment of Non-Native Birds by Providing Underexploited Resources. PLoS ONE, 10(8), e0135833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135833

Sundar, K. G. & Subramanya, S. (2010). Bird use of rice fields in the Indian subcontinent. Waterbirds, 33(sp1), 44–70. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.033.s104

Sundar, K. S. G. (2020). Woolly-necked Stork: a species ignored. SIS Conservation, 2, 33–41.

Thabethe, V. (2018). Aspects of the Ecology of African Woolly-necked Storks (Ciconia microscelis) in an Anthropogenic Changing Landscape in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Ph.D. thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Thabethe, V. & Downs, C. T. (2018). Citizen science reveals widespread supplementary feeding of African Woolly-necked Storks in suburban areas of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Urban Ecosystems, 21, 965–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-018-0774-6

Tobolka, M., Zolnierowicz, K. M. & Kieliszek, J. (2013). Nesting success and productivity of White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) in relation to habitat and social factors. North-Western Journal of Zoology, 9(1), 37–44.

Vaghela, U., Sawant, D. & Bhagwat, V. (2015). Woolly-necked Storks Ciconia episcopus nesting on mobile-towers in Pune, Maharashtra. Indian Birds, 10(6), 154–155.

Vaitkuvienė, D. & Dagys, M. (2015). Twofold increase in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) population in Lithuania: a consequence of changing agriculture? Turkish Journal of Zoology, 39, 144–152. https://doi.org/10.3906/zoo-1402-44

Vyas, R. & Tomar, R. S. (2007). Rare clutch size and nesting site of Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Chambal River Valley. Newsletter for Birdwatchers, 46(6), 95.

Edited By

Upasana Ganguly

University of Louisiana at Lafayette, USA

*CORRESPONDENCE

Ramesh Roshnath

✉ roshnath.r@gmail.com

Navin P. Mathew

✉ navinpmathew@gmail.com

SPECIAL ISSUE

This paper is published in the Special Issue ‘Master’s Dissertations’. It was M.S. dissertation work of Navin P. Mathew.

CITATION

Roshnath, R., Amal, U. K. & Mathew, N. P. (2025). Nest-site Selection and Adaptability of the Asian Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Human-dominated Landscapes of Kerala, India. Journal of Wildlife Science, Online Early Publication, 01-05 . https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.DBPL7531

FUNDING

This study was funded by the Kerala Forest and Wildlife Department, Government of Kerala to Ramesh Roshnath.

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Roshnath, Amal & Mathew. This is an open-access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The informa¬tion contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alonso, J. C., Alonso, J. A. & Carrascal, L. M. (1991). Habitat selection by foraging White Storks, Ciconia ciconia, during the breeding season. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69(7), 1957-1962. https://doi.org/10.1139/z91-270

Banerjee, P. (2017). The Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus re-using an old Grey Heron Ardea cinerea nest. Indian Birds, 13, 165.

BirdLife International. (2022). Species factsheet: Ciconia episcopus. Retrieved from http://www.birdlife.org (Accessed on 20 October 2024).

Blozan, W. (2006). Tree measuring guidelines of the Eastern Native Tree Society. Bulletin of the Eastern Native Tree Society, 1(1), 3–10.

Charutha, K., Roshnath, R. & Sinu, P. A. (2021). Urban heronry birds tolerate human presence more than its conspecific rural birds. Journal of Natural History, 55(9–10), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2021.1912844

del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Collar, N., Garcia, E. F. J., Boesman, P. F. D. & Kirwan, G. M. (2020). Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wonsto1.01

Ghimire, P., Ghimire, R., Low, M., Bist, B. S. & Pandey, N. (2021). The Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus: A review of its status, distribution and ecology. Ornithological Science, 20, 2. https://doi.org/10.2326/osj.20.223

Ghimire, P., Pandey, N., Belbase, B., Ghimire, R., Khanal, C., Bist, B. S. & Bhusal, K. P. (2020). If you go, I’ll stay: Nest use interaction between Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus and Black Kite Milvus migrans in Nepal. Birding Asia, 33, 103–105.

Ghimire, P., Panthi, S., Bhusal, K. P., Low, M., Pandey, N., Ghimire, R., Bist, B. S., Khanal, S. & Poudyal, L. P. (2022). Nesting habitat suitability and breeding of Asian Woollyneck (Ciconia episcopus) in Nepal. Ornithology Research, 30(4), 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43388-022-00104-2

Gilbert, N. I., Correia, R. A., Silva, J. P., Pacheco, C., Catry, I., Atkinson, P. W., Gill, J. A. & Franco, A. M. (2016). Are white storks addicted to junk food? Impacts of landfill use on the movement and behaviour of resident White Storks (Ciconia ciconia) from a partially migratory population. Movement Ecology, 4, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40462-016-0070-0

Greeshma, P., Nair, R. P., Jayson, E. A., Manoj, K., Arya, V. & Shonith, E. G. (2018). Breeding of Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus in Bharathapuzha River Basin, Kerala, India. Indian Birds, 14(3), 86–87.

Hancock, J., Kushlan, J. & Kahl, M. P. (1992). Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World. Academic Press, London.

Hasan, M. & Ghimire, P. (2020). Confirmed breeding records of Asian Woollyneck Ciconia episcopus from Bangladesh. SIS Conservation, 2, 47–49.

Ishtiaq, F., Rahmani, A. R., Javed, S. & Coulter, M. C. (2004). Nest-site characteristics of Black-necked Stork (Ephippiorhynchus asiaticus) and White-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Keoladeo National Park, Bharatpur, India. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 101, 90–95.

Katuwal, H. B., Baral, H. S., Sharma, H. P. & Quan, R. C. (2020). Asian Woollynecks are uncommon on the farmlands of lowland Nepal. SIS Conservation, 2, 50–54.

Kittur, S. & Sundar, K. G. (2021). Of irrigation canals and multifunctional agroforestry: Traditional agriculture facilitates Woolly-necked Stork breeding in a north Indian agricultural landscape. Global Ecology and Conservation, 30, e01793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01793

Krishna, N. G., Alam, S., Prakash, S., Yadav, K., Ahmad, S. & Ojha, A. (2024). Understanding the spatio-temporal variation of urbanisation in Kerala, India. GeoJournal, 89(4), 126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-023-10869-0

Kularatne, H. & Udagedara, S. (2017). First record of the Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus Boddaert, 1783 (Aves: Ciconiiformes: Ciconiidae) breeding in the lowland wet zone of Sri Lanka. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 9, 9738–9742. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.2904.9.1.9738-9742

Leveau, C. M. & Leveau, L. M. (2005). Avian community response to urbanization in the Pampean region, Argentina. Ornitologia Neotropical, 16, 503–510.

Mehta, K. (2020). Observations of Woolly-necked Stork nesting attempts in Udaipur city, Rajasthan, India. SIS Conservation, 2, 68–70.

Mehta, K., Koli, V. K., Kittur, S. & Gopi Sundar, K. S. (2024). Can you nest where you roost? Waterbirds use different sites but similar cues to locate roosting and breeding sites in a small Indian city. Urban Ecosystems, 27(4), 1279–1290. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-023-01454-5

Mlodinow, S. G., del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Collar, N., Garcia, E., Boesman, P. F. D. & Kirwan, G. M. (2022). Asian Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus), version 1.1. In Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.wonsto1.01.1

Møller, A. P. (2009). Successful city dwellers: a comparative study of the ecological characteristics of urban birds in the Western Palearctic. Oecologia, 159, 849–858. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-008-1259-8

Neelakantan, K. K. (2004). Keralathile Pakshikal. Kerala Sahitya Academy, Thrissur, Kerala, India, 570 pp.

Onmuş, O., Sıkı, M. & Kılıç, D. T. (2012). Nest site selection and reproductive success in a colony of White Storks (Ciconia ciconia) in western Turkey. Turkish Journal of Zoology, 36(4), 479–489.

Pescador, M. & Peris, S. (2007). Influence of roads on bird nest predation: An experimental study in the Iberian Peninsula. Landscape and Urban Planning, 82(1–2), 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.01.017

Rahmani, A. R. & Singh, B. (1996). White-necked or Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus nesting on cliffs. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 93(2), 293–294.

Ramsar Convention Secretariat. (1971). The Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat. Ramsar, Iran.

Rao, S. & Koli, V. K. (2017). Edge effect of busy high traffic roads on the nest site selection of birds inside the city area: Guild response. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment, 51, 94-101.

Roshnath, R. & Greeshma, C. (2020). Distribution records of Woolly-necked Storks in Kerala, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 12(8), 15800–15805.

Roshnath, R. & Sinu, P. A. (2017). Nesting tree characteristics of heronry birds of urban ecosystems in peninsular India: implications for habitat management. Current Zoology, 63(6), 599–605. https://doi.org/10.1093/cz/zox006

Sashikumar, C., Praveen, J., Palot, M. J. & Nameer, P. O. (2011). Birds of Kerala: Status and Distribution. DC Books, Kottayam, Kerala, India, p.835.

SoIB (2023). State of India's Birds factsheet: Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus (India). https://stateofindiasbirds.in/species/wonsto1/ (Accessed on 01 November 2025)

Srinivasan, J. T. (2010). Understanding the Kole Lands in Kerala as A Multiple Use Wetland Ecosystem. Hyderabad: Research Unit for Livelihoods and Natural Resources.

Sullivan, M. J., Davies, R. G., Mossman, H. L. & Franco, A. M. (2015). An Anthropogenic Habitat Facilitates the Establishment of Non-Native Birds by Providing Underexploited Resources. PLoS ONE, 10(8), e0135833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135833

Sundar, K. G. & Subramanya, S. (2010). Bird use of rice fields in the Indian subcontinent. Waterbirds, 33(sp1), 44–70. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.033.s104

Sundar, K. S. G. (2020). Woolly-necked Stork: a species ignored. SIS Conservation, 2, 33–41.

Thabethe, V. (2018). Aspects of the Ecology of African Woolly-necked Storks (Ciconia microscelis) in an Anthropogenic Changing Landscape in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Ph.D. thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.

Thabethe, V. & Downs, C. T. (2018). Citizen science reveals widespread supplementary feeding of African Woolly-necked Storks in suburban areas of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Urban Ecosystems, 21, 965–973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11252-018-0774-6

Tobolka, M., Zolnierowicz, K. M. & Kieliszek, J. (2013). Nesting success and productivity of White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) in relation to habitat and social factors. North-Western Journal of Zoology, 9(1), 37–44.

Vaghela, U., Sawant, D. & Bhagwat, V. (2015). Woolly-necked Storks Ciconia episcopus nesting on mobile-towers in Pune, Maharashtra. Indian Birds, 10(6), 154–155.

Vaitkuvienė, D. & Dagys, M. (2015). Twofold increase in White Stork (Ciconia ciconia) population in Lithuania: a consequence of changing agriculture? Turkish Journal of Zoology, 39, 144–152. https://doi.org/10.3906/zoo-1402-44

Vyas, R. & Tomar, R. S. (2007). Rare clutch size and nesting site of Woolly-necked Stork (Ciconia episcopus) in Chambal River Valley. Newsletter for Birdwatchers, 46(6), 95.