TYPE: Research Article![]()

RECEIVED 02 October 2025

ACCEPTED 24 November 2025

ONLINE EARLY 19 December 2025

PUBLISHED 22 December 2025

Abstract

This study analyses the development and status of the Indian captive population of the endangered lion-tailed macaque with reference to the global historical zoo population of the species. Lion-tailed macaques are endemic to South India and have been kept in zoos globally for more than a hundred years. In the year 2018, the global captive population comprised 516 individuals in 98 zoos spread over 30 countries. Recent studies reveal that the development of the historical and current populations has not been satisfactory due to low productivity and other problems. Our study intends to assess the potential of the Indian subpopulation for conservation breeding and whether it can be used to support the global core European population, and to function as a reserve for the wild population. It is found that the status of the captive population in India is poor and needs improvements in terms of size, structure, keeping systems, and management. We propose that the management of living conditions must consider the most critical aspect, which is the female-bonded social system in lion-tailed macaques. This would support breeding and welfare. To achieve this goal, it is proposed to closely cooperate with the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria’s EAZA Ex-situ Programme (EEP) by exchanging know-how and introducing lion-tailed macaques from the EEP population. The management would profit from training systems for zoo personnel on all levels, with emphasis on the biology of lion-tailed macaques and their adaptive potential under the altered conditions in zoos. It is suggested to have a less centralised management system.

Keywords: Captive history, conservation breeding, EAZA Ex-situ Programme (EEP), Indian captive population, Lion-tailed macaque, zoo management.

Introduction

Lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus), endemic to the Western Ghats Mountain range of South India, are threatened by extinction. The species is classified as Endangered on the IUCN Red List (Singh et al., 2020) and listed in Appendix I of the CITES (CITES, 2025). In India, the lion-tailed macaque is a highly protected species, categorised under Schedule I of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. According to Kavana et al. (2025), the total population in the wild is estimated 4,219 individuals, distributed across 237 groups. The population suffers from fragmentation and other human-induced alterations of their habitats, like tea plantations, settlements, roads, high-tension power lines, and hunting (Molur et al., 2003; Kumara & Sinha, 2009; Singh et al., 2020; Dhawale & Sinha, 2025). Two genetically distinct subpopulations of the species have been identified north and south of the 40 km long Palghat Gap (Ram et al., 2015). Lion-tailed macaques have been kept in zoos for more than a hundred years (Lindburg, 2001; Begum et al., 2022). In the year 2018, the global captive population comprised 516 individuals in 98 zoos spread over 30 countries (Sliwa & Begum, 2019). Recent studies by Begum et al. (2022, 2023) reveal that the development of the historical population has not been satisfactory due to low productivity and other problems. Low productivity was found to be influenced by management and husbandry systems which did not sufficiently consider the specific social way of living in permanent female-bonded groups with a modal size of 16–21 individuals in contiguous forests (see Kumar, 1987; Ramachandran & Joseph, 2000; Kumara & Singh, 2004; Kumara et al., 2014; Sushma et al., 2014; Singh, 2019). Management also did not consider that only males leave their natal groups and join other groups (see Kumar et al., 2001). For details on the biology of the species, see Singh & Kaumanns (2005), Singh (2019), and Begum (2023). The global captive population decreased over the last decade to a core population in Europe of 322 individuals, and a few other (small) subpopulations, including the Indian population with about 51 individuals (status as of 2018; for details of the development, see Begum et al., 2021, 2022, 2023). Especially, space problems in the American and European populations led to a management of population size mainly via birth control (Lindburg et al., 1997, Sliwa et al., 2016; Rode-White & Corlay, 2024). It resulted in the attempted smaller populations but also produced problematic side effects in terms of perpetuating low productivity across these populations (see Penfold et al., 2014). The proportion of ageing females growing into an infertile status increased. The formerly large American population decreased to a small number of non-productive individuals. Several descendants of the American population are found in Europe and in smaller subpopulations, but most probably not in the Indian one (see Sliwa & Begum, 2019). For a more elaborated and differentiated discussion of the potential effects of birth- control on population size (see Begum et al. 2022, 2023). The authors propose that the productivity of a population may be linked to a population’s “natural” growth patterns and size.

The results of Begum et al. (2021, 2022, 2023) studies indicate that the historical captive population of the lion-tailed macaque probably experienced a loss of genetic and phenotypic diversity. To stop the decline and to support the captive population’s long-term persistence (as a reserve for the threatened wild population), a new global management approach must be developed that allows more breeding in large female-bonded groups, despite the space problems European zoos suffer from. It seems that the Indian zoos have the potential to provide the necessary conditions in terms of space. Begum et al. (2021), therefore, proposed that Indian zoos should cooperate closely with the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria’s EAZA Ex situ Programme (EEP), house lion-tailed macaques born in Europe, and serve as an interface between zoos and the wild for reintroductions. They can thus contribute to establishing a larger and more diversified global reserve population. The records available from the International Studbook for the Lion-tailed Macaque and from other sources reveal, however, a poor status of the Indian population and its living conditions, and a strong need for improvements. This especially should refer to the social system of lion-tailed macaques.

The present study aims to analyse the development and status of the Indian subpopulation, to discuss its potential for long-term survival and conservation breeding, and to propose necessary management improvements. Since the results of the investigation are placed and discussed in the context of the global historical captive population of the species, the global population is described briefly. The paper is oriented towards providing comprehensive materials for practical use and should contribute to the conservation of the species via captive propagation. The propositions should contribute to establishing a special management and breeding programme for the Indian lion-tailed macaque population. The establishment of the programme should be significantly supported by the Central Zoo Authority, considering contributions by the individual zoos. Furthermore, the already available husbandry guidelines for the lion-tailed macaque (Kaumanns et al., 2006) should be used, as well as a number of other papers referring to the topic (Kaumanns et al., 2013; Begum et al., 2021, 2022, 2023; Begum, 2023). The existing husbandry guidelines (Kaumanns et al., 2006) point to welfare-based management indicators, for example, the role of social living conditions, feeding ecology, arboreal life, and enclosure complexity.

The study is organised as follows: the first part briefly describes the global historical population, and the second and third parts focus in detail on the Indian historical and living populations, respectively.

Materials and methods

The study is based on the most recent edition of the International Studbook of the species as of 31st December 2018 (Sliwa & Begum, 2019). The terms “current” or “living” population in this study always refer to the status in 2018.

The Studbook provides information on the individual lion-tailed macaques kept globally and in Indian zoos with records from 1899 to 2018 (Sliwa & Begum, 2019). Data include identity, origin, births, deaths, reproductive output, transfers and locations. Group sizes could only be derived from the number of individuals per location. Additional information was taken from relevant publications, wherever available. Due to the small number of individuals in Indian zoos, limited descriptive statistics are used. Conservation and breeding potential are mainly discussed with reference to the reproductive output of the population and the living conditions currently provided, and deficiencies that need to be improved.

The International Studbook for the Lion-tailed Macaque is maintained as an electronic database using the software SPARKS (Single Population Analysis and Records Keeping System v 1.66) (Scobie & Bingaman Lackey, 2012). For analysing various demographic parameters, we used the population management programme PMx v 1.8.1.20250501 (Ballou et al., 2025), available from the Species Conservation Toolkit Initiative (https://scti.tools). The data were organised and analysed using Microsoft Excel and R v 4.5.1 (R Core Team, 2025), and most figures were generated using GraphPad Prism 10.6.0 (GraphPad Software, 2025).

Results and discussion

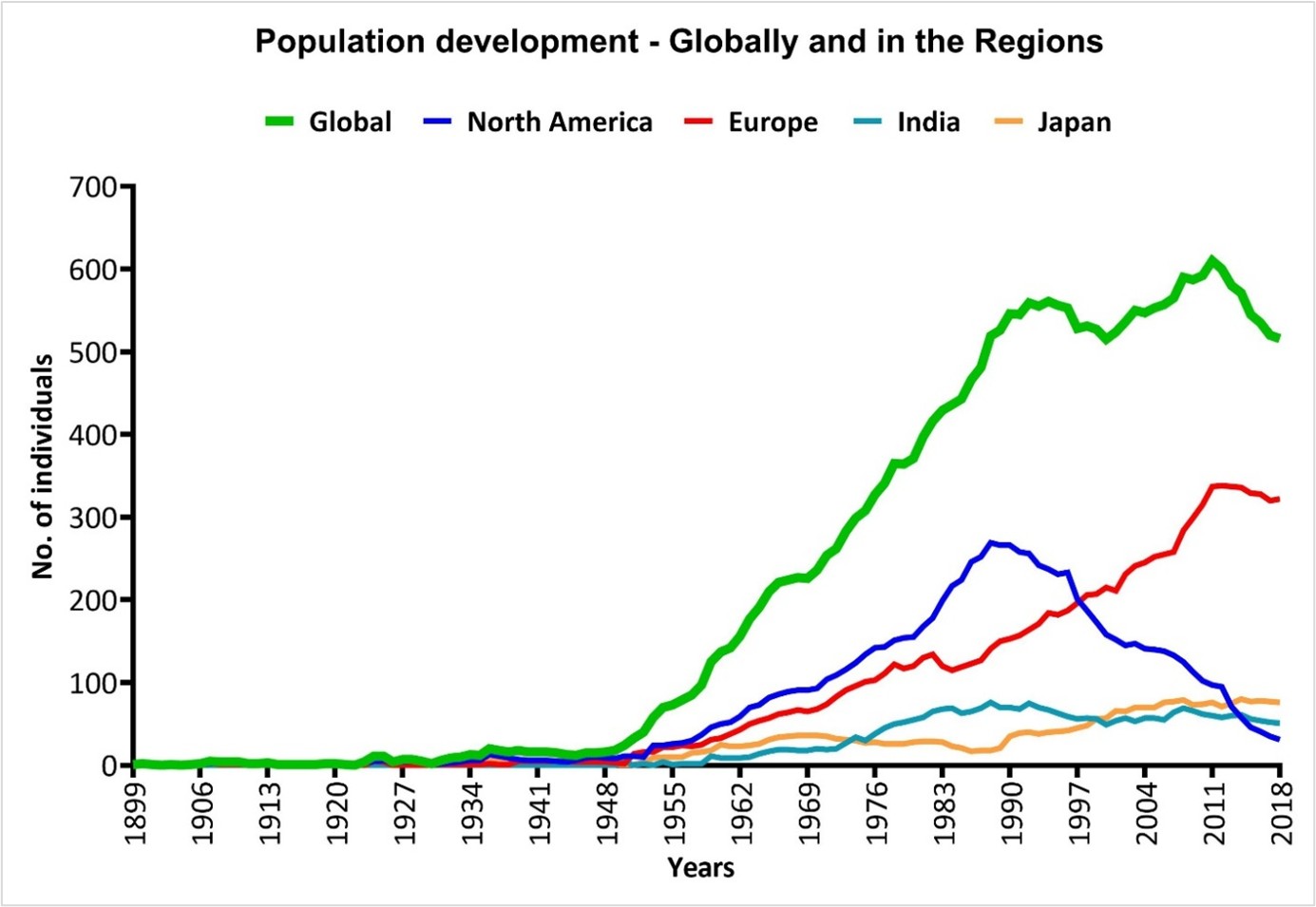

The historical trend of the global captive population of lion-tailed macaque can be roughly divided in four periods (Figure 1). Between the end of the 19th century and about 1950, the number of individuals and births was small. Both increased slightly until the 1970s, followed by a significant increase till the 1990s, with the highest number of individuals (n = 561) recorded in 1994. From this “prime-time” onwards, the size of the population decreased. No further increase was due to a strong management-induced shrinking of the American subpopulation (see Lindburg, 2001) – “compensated” by an increase in the European subpopulation, which played a dominant role since the mid-1990s. The global population has been declining since 2011–2012, mainly due to management measures implemented in Europe (see Sliwa et al., 2016). Among the smaller subpopulations, the Japanese population remained stable, while the size in India is shrinking (see later). As of 2018, Europe constituted 62% of the global population, followed by Japan and India, which comprise 15% and 10% of the population, respectively. The North American population has been reduced to a small, ageing population of 31 individuals.

The large populations were embedded in breeding programmes (Species Survival Plan SSP) in North America, and European Endangered Species Breeding Programme/ EAZA Ex situ Programme (EEP) in Europe in the years 1983 and 1989, respectively. In India, a breeding programme was established in the mid-2000s (CZA Guidelines, 2011).

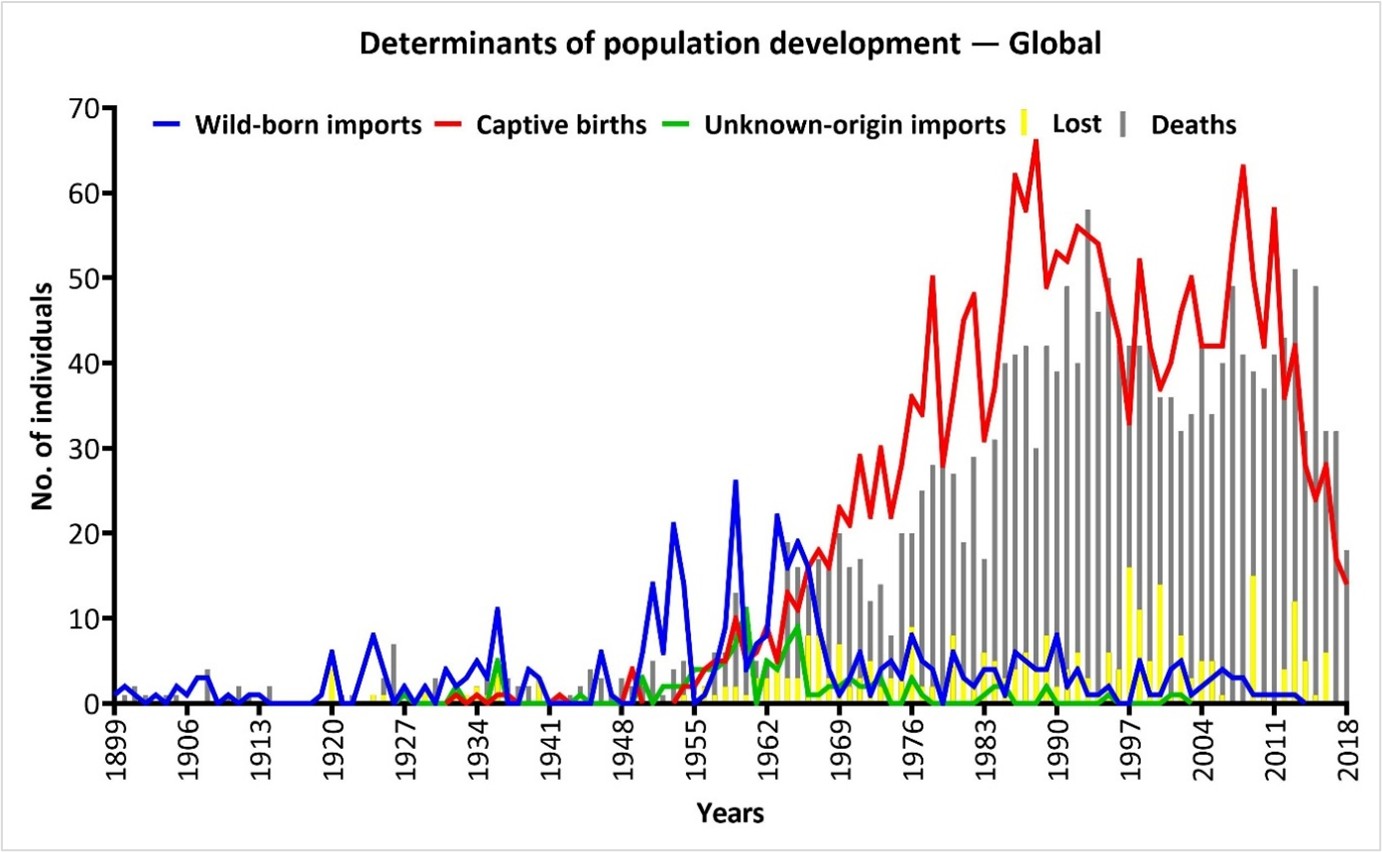

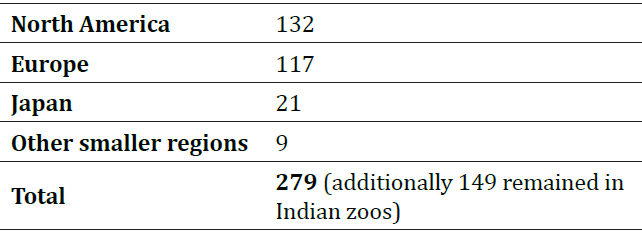

The increase of the global captive population in its first decades was mainly contributed by wild-caught lion-tailed macaques. A total of 428 wild-born individuals (183 males, 209 females, 36 unknown sex) were recorded between 1899 and 2018 (Figure 2, Table 1). In the early period, India transferred 249 wild-born individuals to North America (n = 132, c.31%) and Europe (n = 117, c.27%), thus “establishing” these big populations. Smaller numbers of wild-born individuals were

Figure 1: Development of the global population of lion-tailed macaques in captivity. Adapted with permission from Begum et al. (2022), published in Primate Conservation

Figure 2: Population dynamics in the global captive lion-tailed macaque population over time. Adapted with permission from Begum et al. (2022), published in Primate Conservation

Table 1: Transfer of wild-caught individuals to zoos outside India between 1899 and 2018.

transferred to Japan (n = 21, c.5%) and other regions (n = 9, c.2%). It seems that these transfers were executed by animal dealers. Indian zoos kept 149 wild-born individuals (c.35%). A number of individuals were transferred from North America and Europe to other countries, especially in Asia, establishing smaller peripheral populations. For an elaborated account of the transfers and exchanges of lion-tailed macaques between the various regions, see Begum et al. (2022).

From the 1970s onwards, further import of wild-caught individuals was voluntarily banned in zoos in North America and Europe, more breeding was propagated, and the proportion of individuals born into the population increased substantially (see Hill, 1971; Heltne, 1985; Kaumanns & Rohrhuber, 1995). Over the 119-year period (1899–2018), 2,195 births, 1,923 deaths, and 295 individuals lost to follow-up were recorded. North America (691 births) and Europe (1,044 births) together contributed to 79% of the individuals born in zoos globally. The number of births increased till about 1989, which was followed by a decrease due to management-induced population control in North America. The second increase in births in the global population from the early 2000s was contributed by increased breeding in Europe. Over the last decade, the number of births has been declining continuously as a result of birth control measures in Europe and declining birth rates in other subpopulations.

Patterns of management

North America and Europe

Till the 1970s, management and husbandry of captive lion-tailed macaques were mainly organised locally by individual zoos (see Lindburg, 2001; Begum et al., 2022).

The 1980s brought significant collaborative efforts together following the first international symposium on lion-tailed macaques in Baltimore in 1982, leading to the publication of a Studbook in 1983, the establishment of the Species Survival Plan (SSP) in North America (1983), and the European Endangered Species Programme (EEP) in 1989. This resulted in systematic and conservation-oriented management and research in zoos. It included science-based improvements of physical and social living conditions. Breeding and improving breeding conditions were propagated. Progress was achieved in several international lion-tailed macaque symposia (see Singh et al., 2009; Begum et al., 2021).

The European and North American breeding programmes contributed the most to the global population, where both the subpopulations grew via captive breeding alone, without further imports (see Begum et al., 2022). Since the end of the 1980s, however, these two large breeding programmes have developed different management strategies and goals. A key development in the 1990s was the management-induced shrinking of the North American subpopulation (steady-state management, Lindburg et al., 1997), a decrease in their housing zoos, a reduction in group sizes, and export of individuals to other regions, resulting in a small (and non-productive) subpopulation (Figure 1). The European subpopulation, on the other hand, was managed by the EEP to grow steadily, and the establishment of large groups was propagated (Kaumanns et al., 2013). Comprehensive overviews of the management of the American and European populations are presented in several publications (Lindburg et al., 1997; Lindburg, 2001; Kaumanns et al., 2001, 2013).

India

Conservation-oriented work in zoos in India is more recent compared to North America and Europe. A preliminary approach to a systematic breeding programme in India emerged in the 2000s. The Central Zoo Authority (CZA) in India identifies one large zoo in the distributional range of a target species as a coordinating zoo for breeding the selected species. The coordinating zoo is responsible for establishing the initial founding stock and developing off-display breeding centres as per designs approved by the CZA. This zoo is supposed to coordinate with a few more zoos (usually 2–4) that are also close to the species’ distributional range and have been identified by the CZA as participating institutions in the programme. The participating zoos are responsible for maintaining satellite populations once sufficient numbers are bred at the coordinating zoo (see CZA Guidelines, 2011).

The breeding programme for the lion-tailed macaque in India deviates from the international programmes described above in terms of the management system as presented. It does not include all individuals of the Indian captive population and all zoos. It rather included three selected zoos (Vandalur, Mysore, and Thiruvananthapuram) in the range states (Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Kerala) of the species only (see above, CZA Guidelines, 2011). The management of the lion-tailed macaque programme is also organised in a centralised manner by the CZA and Vandalur Zoo as the coordinating zoo, and to a limited extent by the two other participating zoos. Since the number of participating institutions is only three, many other zoos keeping lion-tailed macaques are excluded and are not managed systematically.

Lion-tailed macaques in many Indian zoos were often kept in small and barren enclosures (Mallapur et al., 2005a, b; Begum, pers. observation). Zoos that participate in the breeding programme may keep individuals in off-exhibit areas, but may also use enclosures that are open to the public. The coordinating zoo is specifically financially supported by the CZA.

The Indian historical captive population

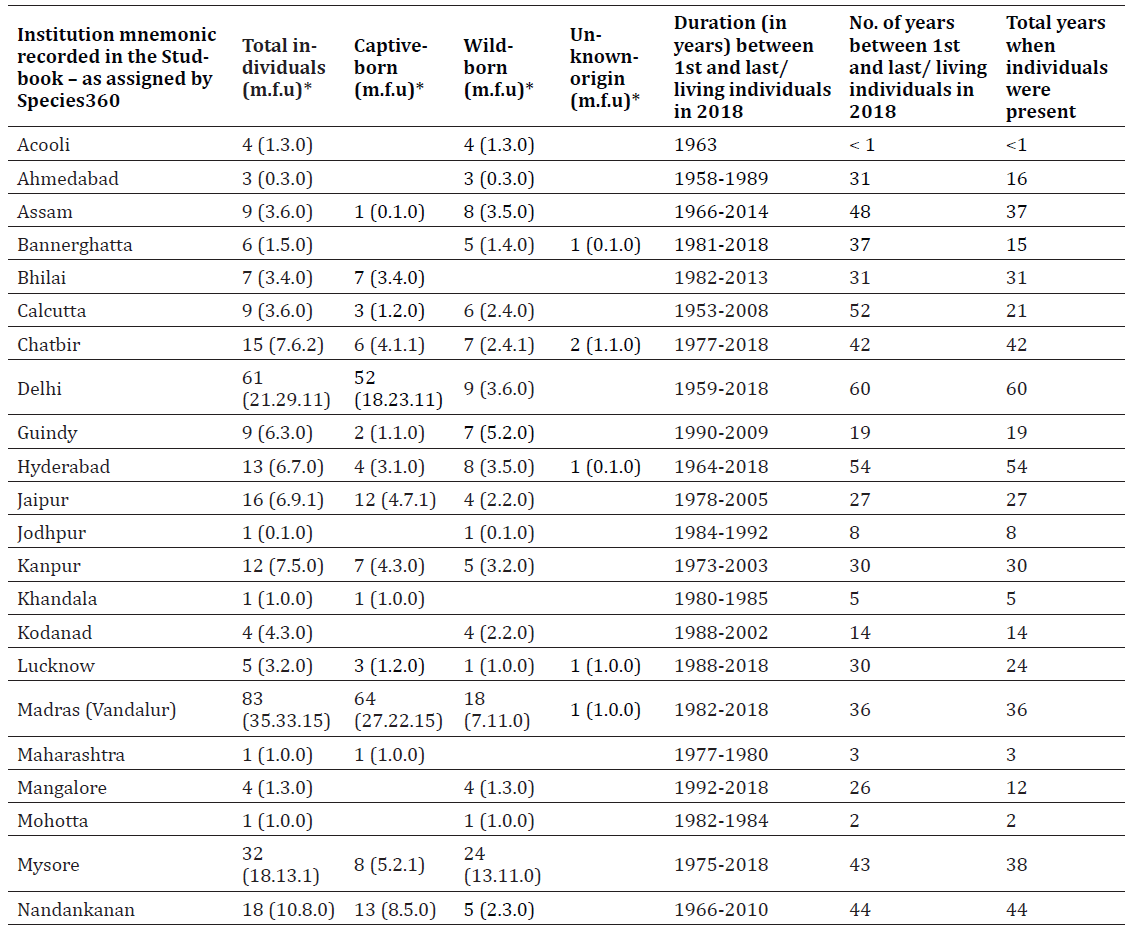

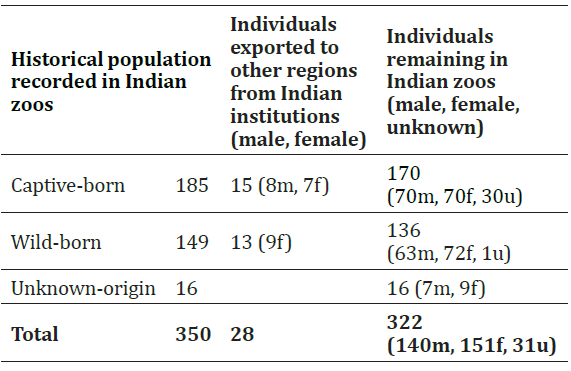

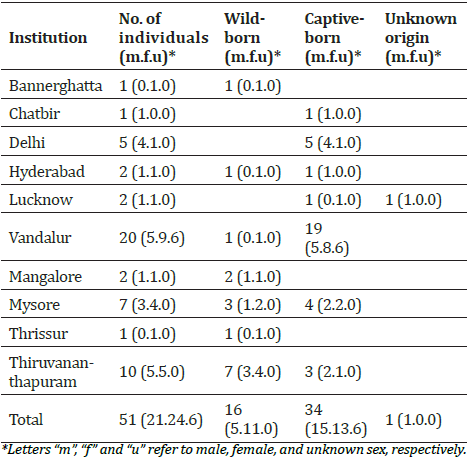

Historically, a total of 350 individuals were recorded in 36 Indian institutions, as derived from the International Studbook (Table 2; Sliwa & Begum, 2019). Most institutions kept only a few individuals. The list includes 28 individuals who were transferred to other regions (see later).

Population development

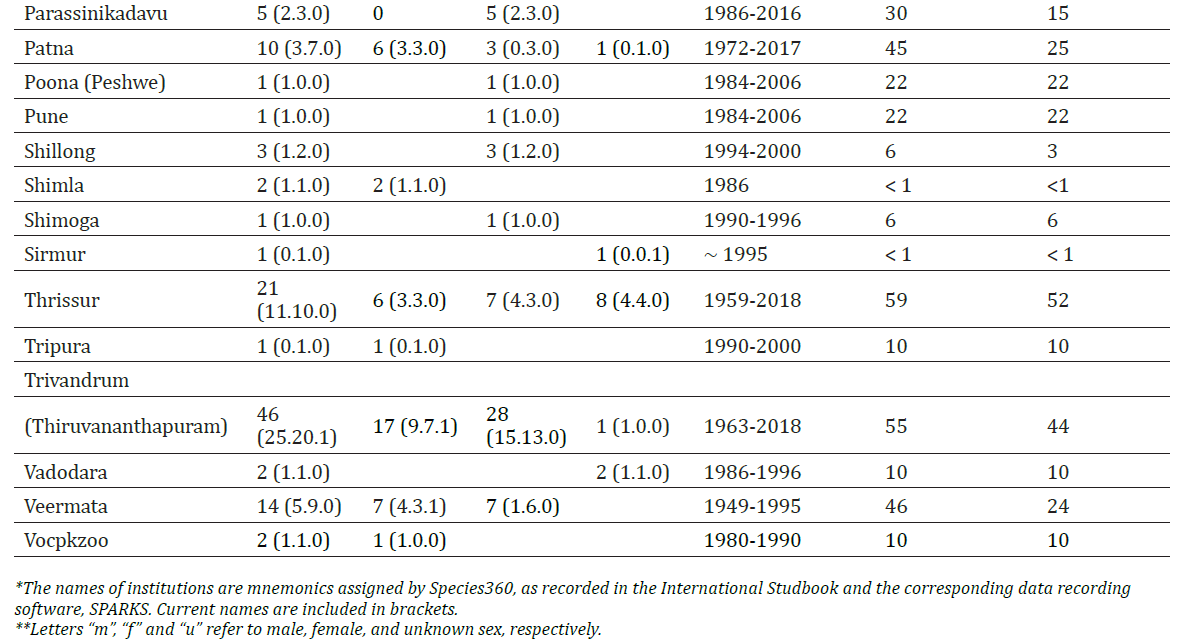

Although a few individuals in a few zoos were recorded since late 1949, the regular keeping of lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos can be traced since 1959. A total of 350 individuals (152 males, 167 females, 31 unknown sex) have been kept so far, with a mean (±SD) of about 42 ± 24.83 individuals per year.

The population increased till the early 1990s and decreased continuously till 2000 (Figure 3). After a period of some increase during 2001–2008, the population has been declining overall (lambda, λ = 0.909). As of 2018, the population consists of 51 individuals in 10 zoos (Figure 3).

Historically, over about 70 years (1949–2018), approximately 53% of the lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos were captive-born, 43% were wild-born, and 4% were of unknown origin (Table 3). Between 1950 and 2018, the mean number (±SD) of captive-born individuals was 19.75±14, and the mean number (±SD) of wild-born and unknown-origin individuals was 21.63±11.2.

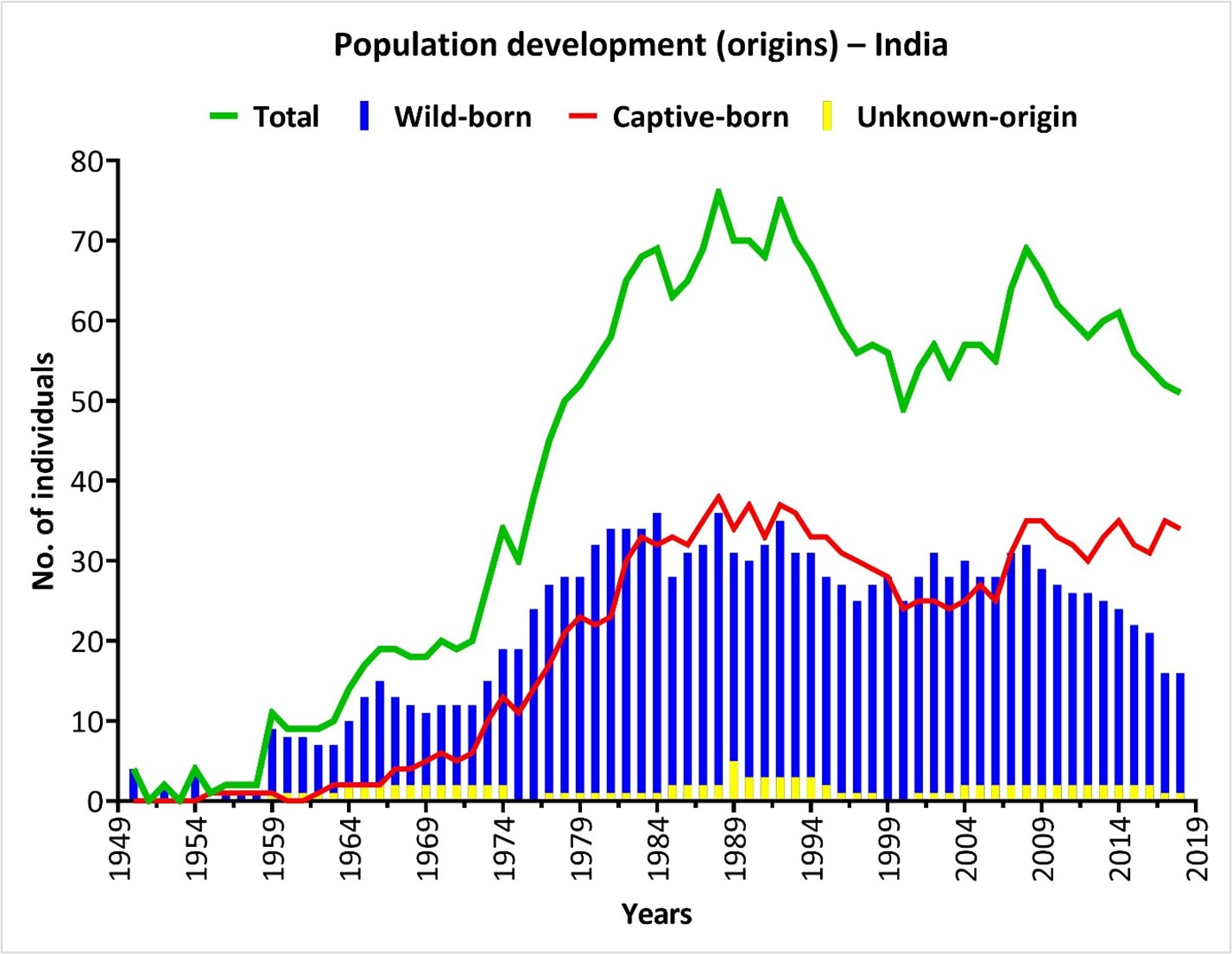

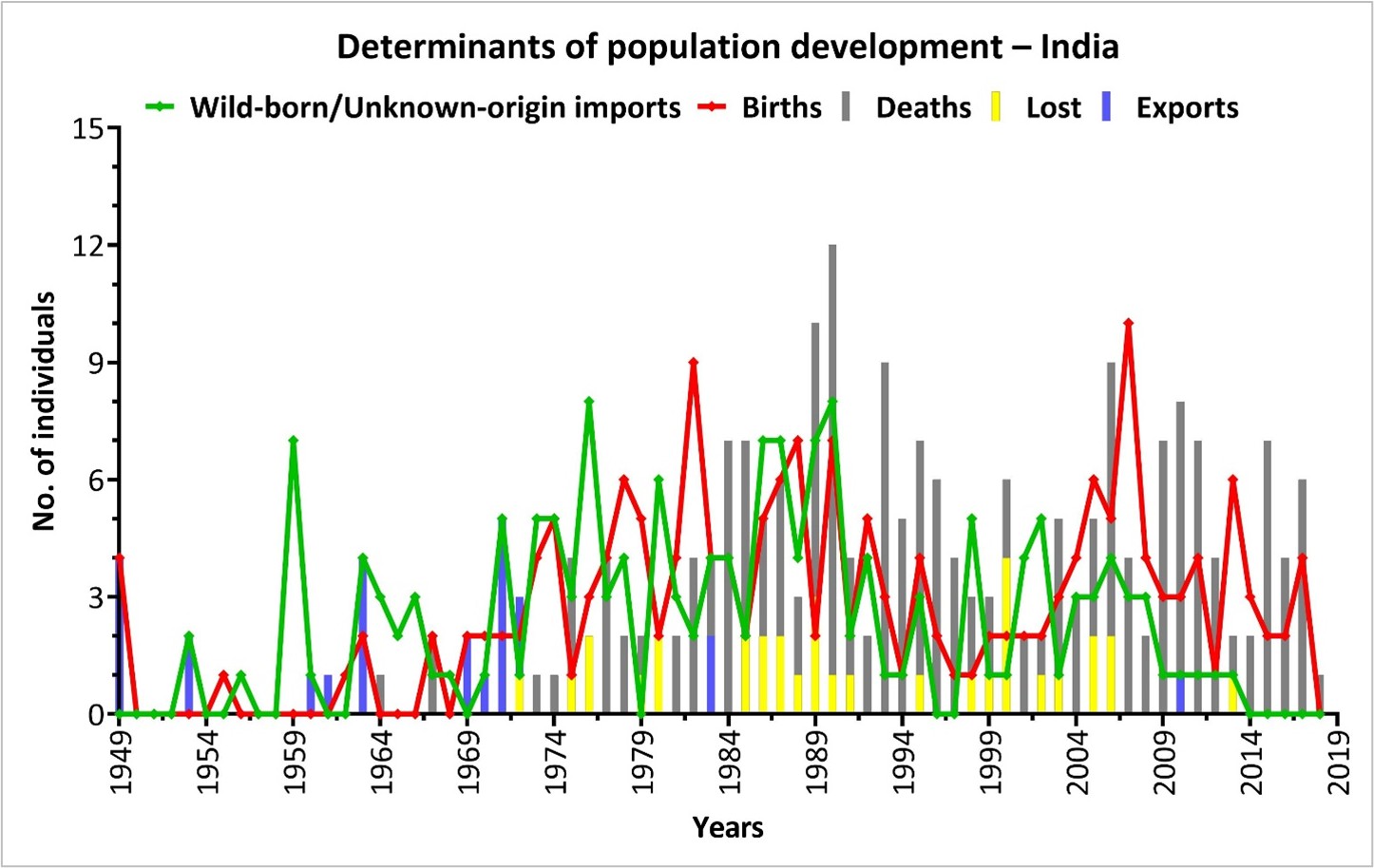

Determinants of population development

The development of the Indian population was influenced by the integration of wild-caught and unknown origin individuals (n = 165), captive births (n = 185), and a few transfers (n = 28) to other regions (see Table 3, Figure 4). A total of 213 deaths and 33 individuals lost to follow-up were recorded. Births, as recorded continuously from 1969 onwards, increased until 1982, declined till 1998, increased again till 2007, and have

Table 2: Historical captive population of the Lion-tailed macaque in Indian zoos

Figure 3: Development of the captive population of lion-tailed macaques in India.

been decreasing since then. The mean (±SD) number of births per year (2.64±2.3) was consistently lower than the mean (±SD) number of deaths, lost to follow-up and exports (3.91±3.33).

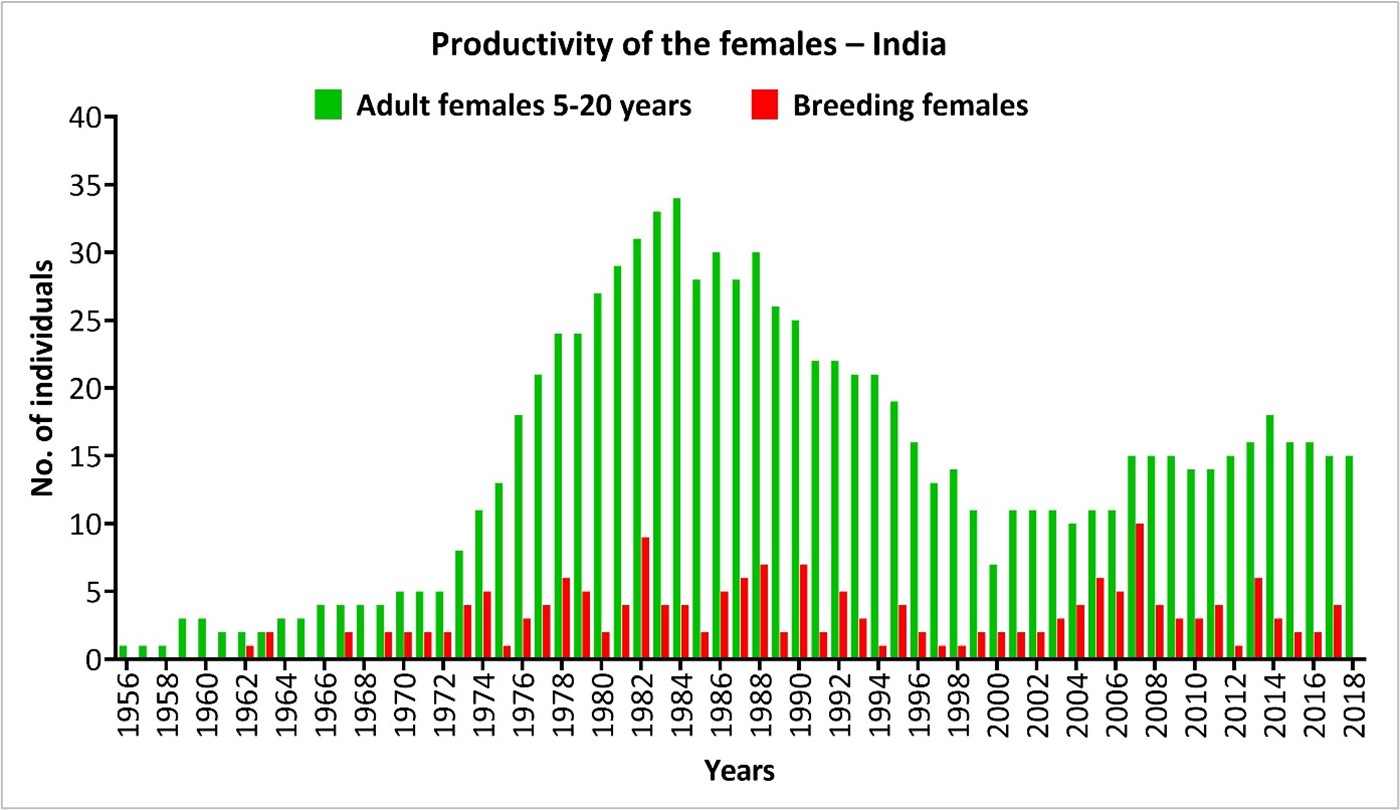

Patterns of reproduction

An important reason for the poor development of the population was the low productivity of the individual females (see Figure 5). Between 1969 and 2018 (period of regular births), a mean (±SD) of 17.48±7.92 (median 15.5; range 5–34) adult females were recorded; however, a mean (±SD) of only 3.5±2.1 (median 3; range 0–10) adult females bred per year. The figure also reveals the increase in the number of females aged 5–20 years from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s, and a continuous decline until 2000. In the last two decades (1995–2018), the number of females of reproductive age remained less than 20 per year, and the number of breeding females exceeded five only at three times.

Figure 4: Annual numbers of births, imports of wild-born, and unknown origin individuals, deaths, exports, and lost individuals (based on 149 wild-born, 14 unknown origin, 185 captive-born, 213 dead, 33 lost to follow-up and 28 exported individuals) of the captive lion-tailed macaque population in India.

Table 3: Origins and exports of lion-tailed macaques from Indian zoos from 1949 onwards.

Figure 5: Annual number of adult females (5–20 years) and breeding females in the captive population of lion-tailed macaques in India.

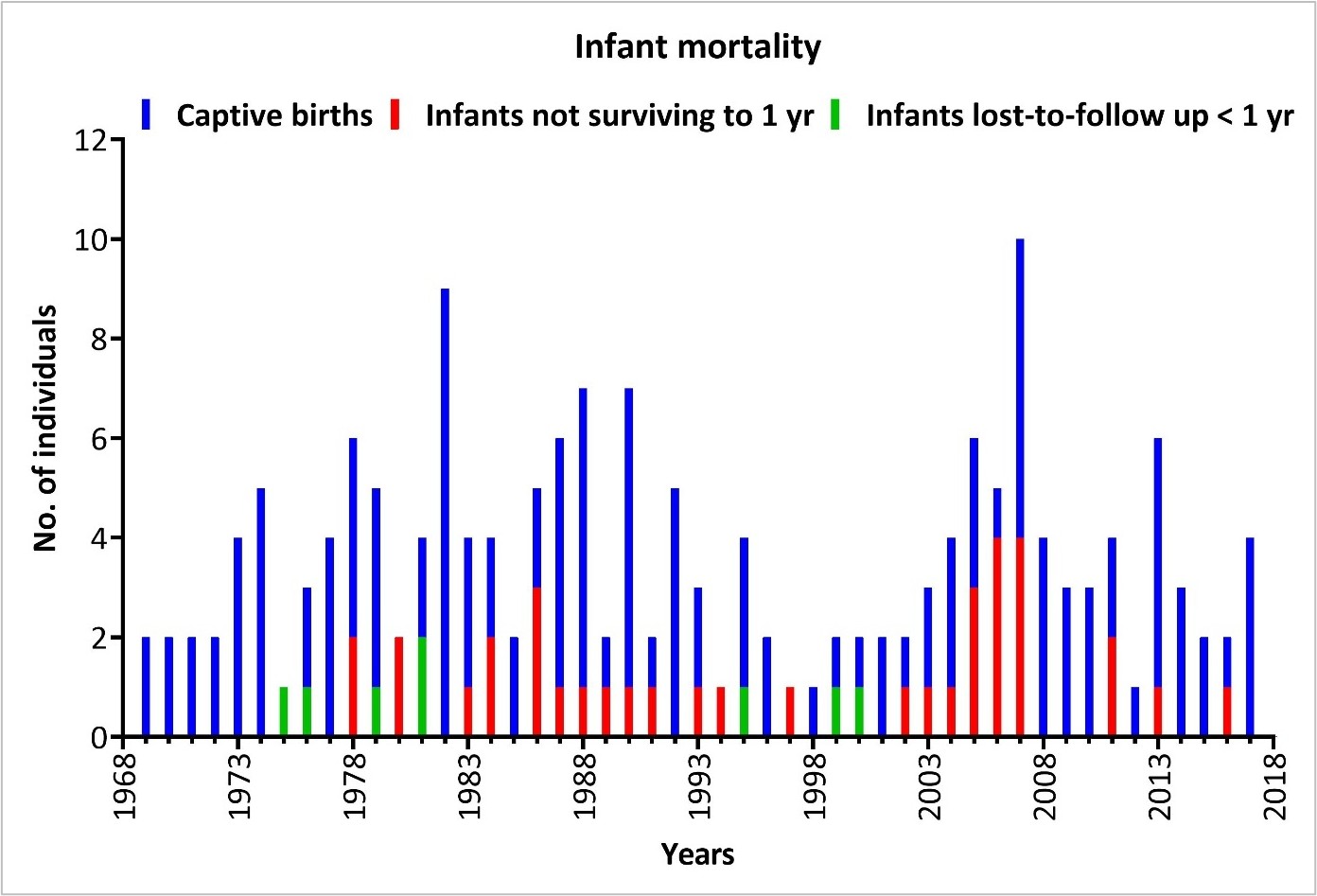

Totally, 19% (n = 36) of the offspring born into the population died at less than 1 year of age (Figure 6), and another 12 offspring were lost to follow-up at less than 1 year after birth. Furthermore, another 11% (n = 20) either died (n = 17) or were lost to follow-up (n = 3) between the ages of 1 and 5 years. Therefore, about 26% of the captive-born individuals did not survive the first year of life, and a total of 37% of the individuals born were not available for breeding.

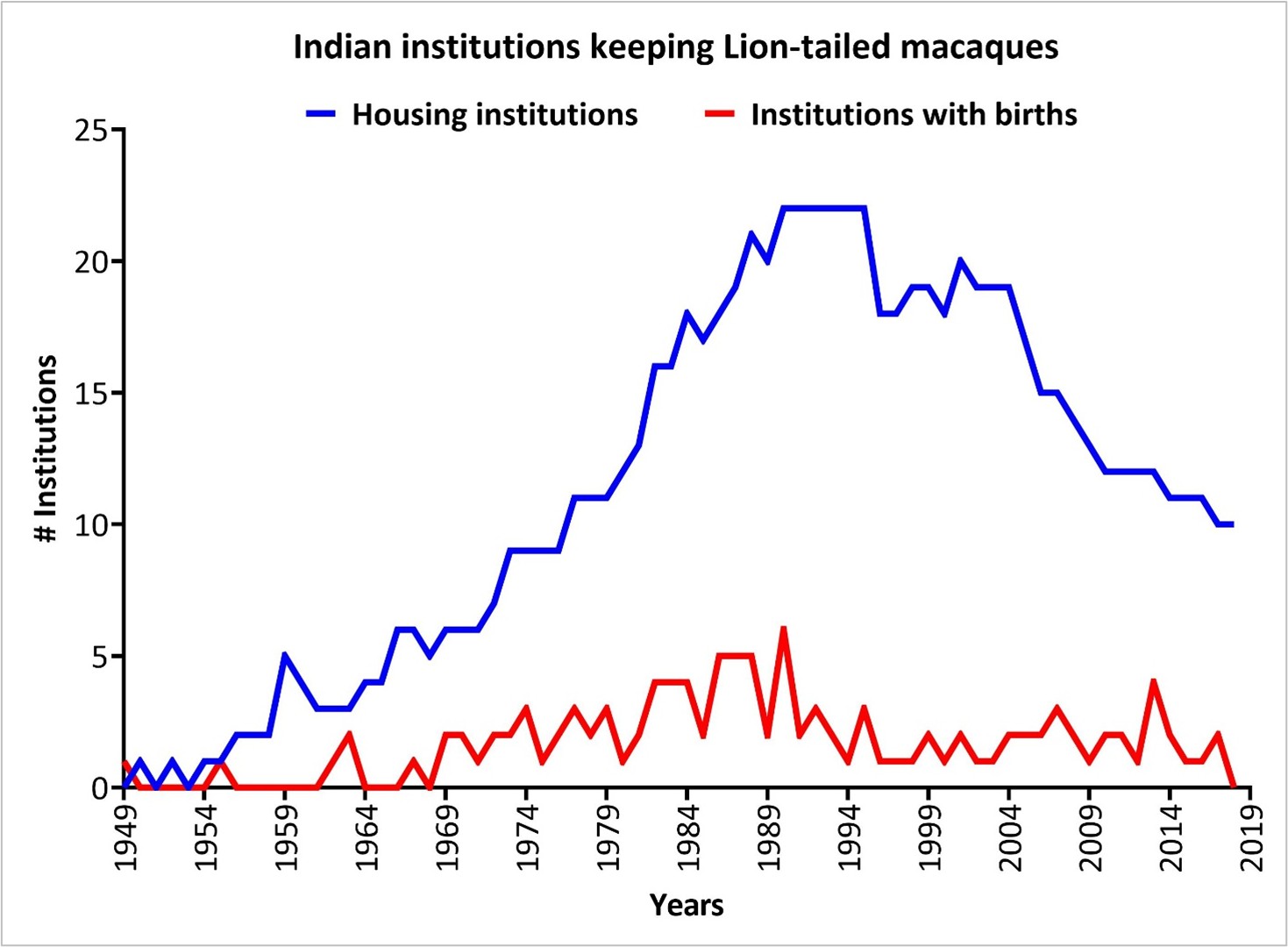

The number of institutions that kept lion-tailed macaques increased until about 1990 to 22 zoos and remained constant till 1995 (Figure 7). The numbers have been declining continuously, especially since 2001, reaching 10 zoos in 2017 and 2018, the lowest recorded in the last four decades (1977–2018).

The number of zoos in which breeding occured per year remained low (Figure 7). Between 1969 and 2018, a mean of 2.22±1.28 zoos (median 1, range 0–6) recorded births per year, with maximum six zoos with births in 1990. Since 1991, the

Figure 6: Annual number of births, infant deaths <1 year, and infants lost to follow-up < 1 year in the captive lion-tailed macaque population in India.

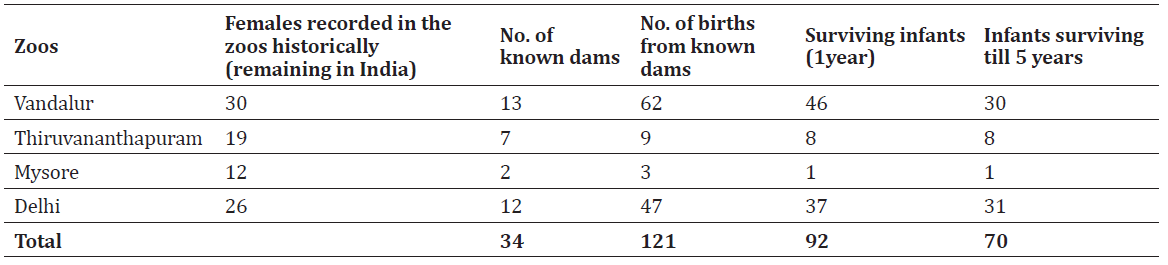

number of institutions with births has remained consistently low (0–4). The majority of the 185 births occurred in three zoos: Vandalur (c. 35%, n = 64), followed by, Delhi (c.27%, n = 49) and, Thiruvananthapuram (c.8%, n = 15), out of which Delhi zoo was a non-participant in the breeding programme, but contributed to births, especially in the 1970s (Table 4).

Another 39 infants were contributed by 16 females (including one that also bred in Thiruvananthapuram) across nine other zoos.

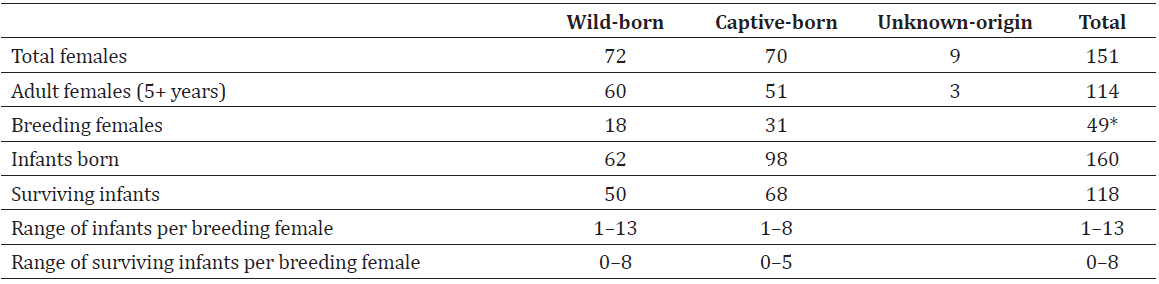

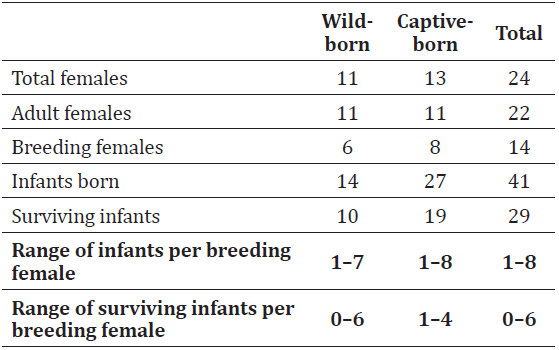

Reproductive output of the females

In the Indian historical captive lion-tailed macaque population, only 32% (n = 49) of the 151 females bred at all; this constitutes about 43% of the available adult females (n = 114) (see Table 5). When accounting for surviving infants only (n = 118), less than 29% (n = 43) of the females and about 38% of the adult females contributed to successful reproduction in the population. Females breeding in Indian zoos constituted only about 10% of the total 500 breeding females recorded in the global historical population.

Figure 7: Indian institutions keeping lion-tailed macaques and recording births of individuals.

There were large differences in the reproductive output between the females, ranging from 1 to 13 infants and 0 to 8 surviving infants. About 45% (n = 22) of the breeding females produced 1–2 infants per female lifetime, accounting for approximately 19% (n = 30) of the infants with known mothers. Only 12 females, forming 24% of the breeding females, produced five or more infants per female lifetime and contributed to 50% of the infants born to known mothers.

A total of 26% of the infants born to known mothers did not survive to the age of 1 year. Among the wild-born females, only 25% (n = 18) bred, contributing to 50 surviving infants.

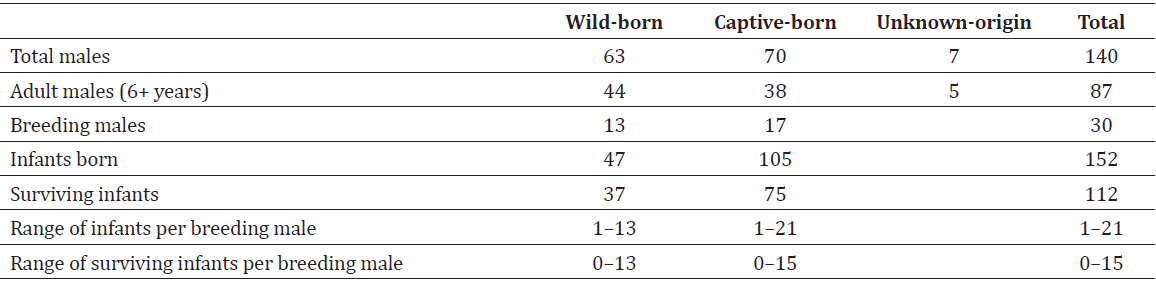

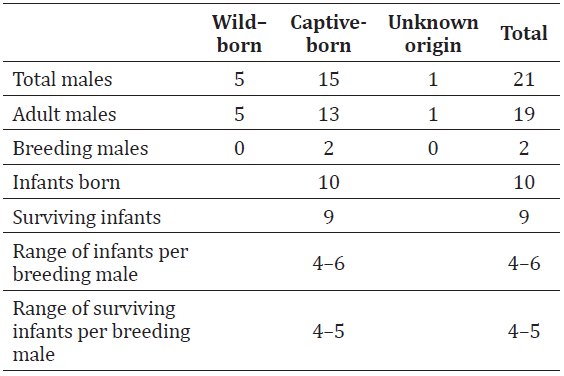

Reproductive output of the males

The Indian captive historical population comprised 140 males, of which about 21% (n = 30) contributed to breeding at all, with fewer (c.19%, n = 26) contributing to surviving infants (Table 6). Based on the origin, 21% of the wild-born males and 24% of the captive-born males bred. Large differences in terms of individual reproductive output were found: 65% (n = 99) of the infants with known sires were produced by only seven males, which comprise about 23% of the breeding males recorded.

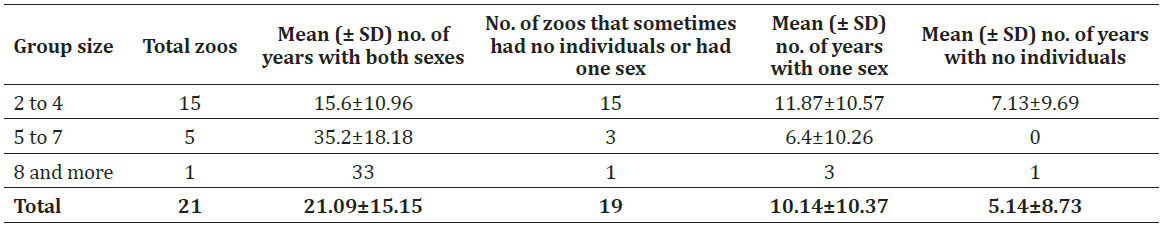

Composition of groups

Since the social way of life is an important aspect in the lives of primates, this is referred to by analysing the composition of the units in which lion-tailed macaques in the Indian population were kept. The “total historical colony size” refers to the overall number of individuals recorded in a zoo throughout its history. Out of the 36 institutions documented in the International Studbook, 24 had historical colony sizes of less than 10, including 17 zoos that kept fewer than 5 individuals in their captive history. In terms of group composition, 15 zoos either did not keep individuals of both sexes, or did not house both sexes together for more than a year. Most of these zoos kept a single individual at a time.

In the remaining 21 zoos that maintained heterosexual units, the median group size each year ranged from 2 to 13, with 20 zoos recording a size of 2 to 7 individuals (Table 7). In these heterosexual groups, over 71% (n = 15) had 2 to 4 members per year; five groups had 5–7 members, while only one group exceeded 8 members per year.

Table 4: Breeding of lion-tailed macaques in the three institutions participating in the conservation breeding programme and the non-participating Delhi zoo, India.

Table 5: Individual reproductive output of the females in the historical captive population of lion-tailed macaques in India.

Table 6: Individual reproductive output of the males in the historical captive population of lion-tailed macaques in India.

Most of the heterosexual units (n = 19) also experienced discontinuity and had periods during which either no individuals or only single-sex individuals were kept. Overall, most of these groups consisted of less than 5 members; keeping individuals in solitary conditions was, and is, not rare.

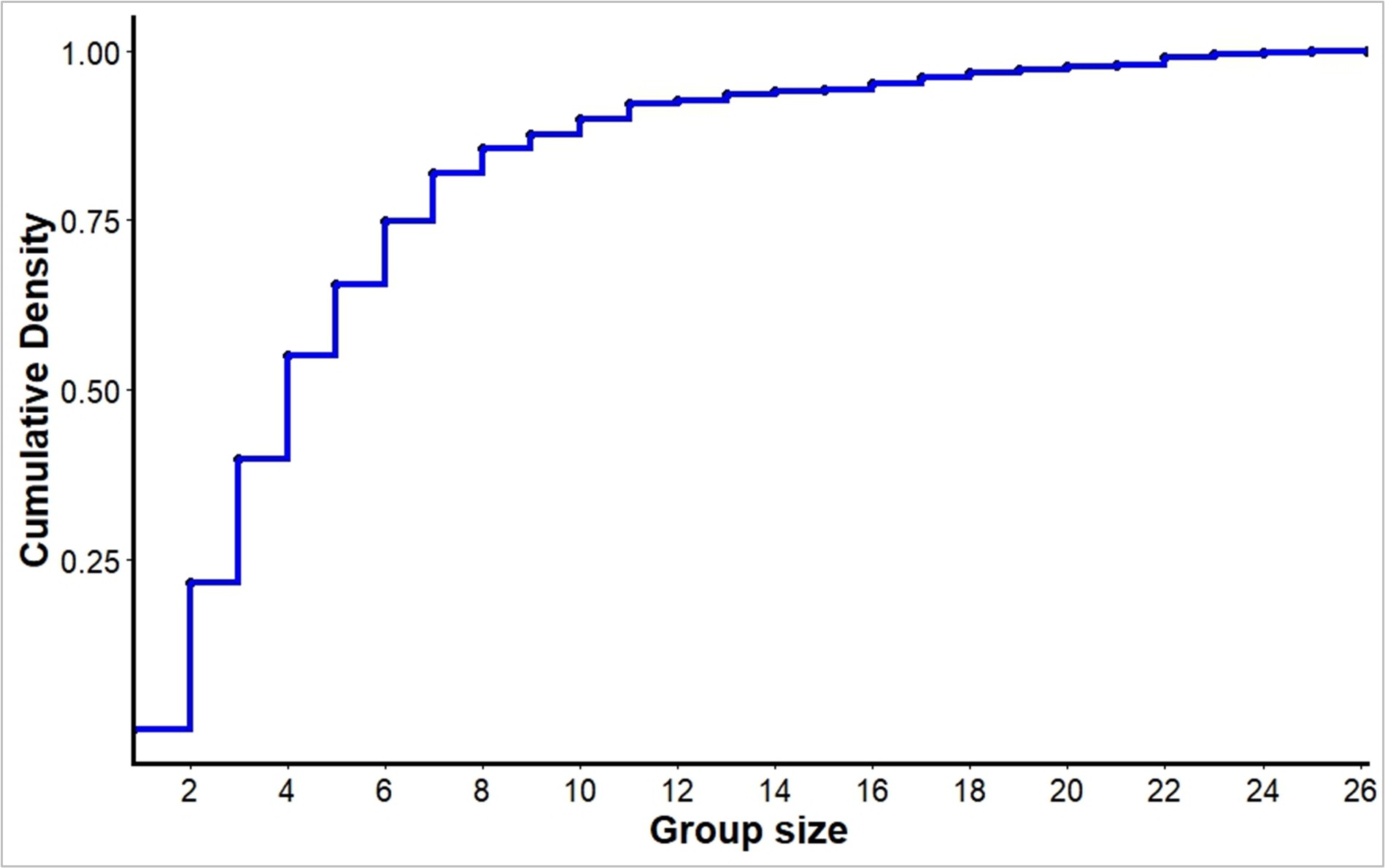

In order to describe and visualise the distribution of group sizes over the years, the empirical cumulative distribution function was applied. The analysis uses the number of individuals in heterosexual groups of two or more members, as recorded at the end of each year from 1959 to 2018. For the heterosexual groups, approximately 75% of the groups had fewer than seven members throughout the complete history of the population (Figure 8, Table 8).

Transfer of individuals between zoos

Population dynamics were influenced by the integration of wild-caught individuals (see above) and also by the transfer of individuals between zoos.

Females

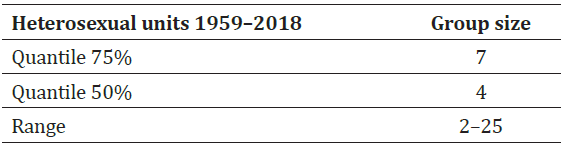

A total of 15 captive-born females were removed from their natal groups and transferred to other zoos within India(additionally, seven females were transferred to five regions, Table 3).

The mean (±SD) age at removal of females from natal groups was 7.11±4.29 years. Six out of the 15 females were transferred at less than 5 years of age as young juveniles and infants. Among the transferred females, seven individuals bred at all: four bred in the new group, and three bred in the natal group before transfer. The latter produced 14 infants, of which 12 survived (see Figure 9). Of the 55 captive-born females remaining in their natal groups, 24 bred and contributed to 75 infants. Overall, about 80% (n = 78) of the infants, and 82% (n = 56) of the surviving infants produced by captive-born females were born in the respective natal group of the dam.

Wild-born (n = 18) and unknown-origin (n = 1) females were sometimes transferred to more than one zoo after capture from the wild. About 74% (n = 14) of these transferred wild-born and unknown-origin females did not breed at all. After capture from the wild, only one individual bred in both the first group and the new group, while four individuals bred in the new group only.

Table 7: Composition of the heterosexual groups of lion-tailed macaques kept in Indian zoos.

Figure 8: Distribution of sizes in heterosexual groups of captive lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos.

Table 8: Distribution of group sizes in the Indian historical captive population of lion-tailed macaques.

Males

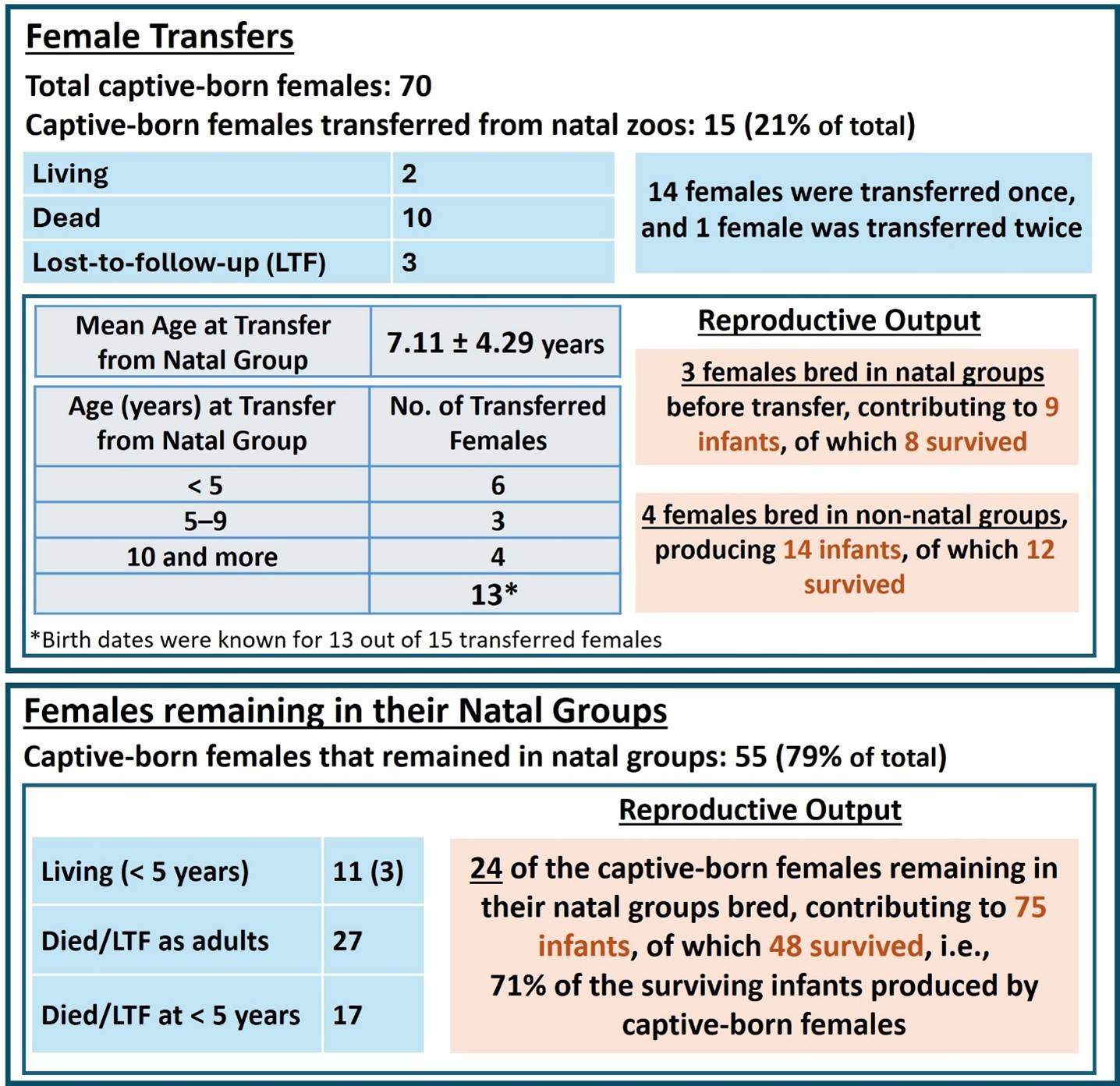

Of the 70 males born into the population, about 29% (n = 20) were transferred from their natal zoos to other locations within India (Figure 10). Additionally, eight individuals were transferred to other regions; therefore, these individuals have been excluded from the analysis of male transfers in India. Half of the males (n = 10) were transferred at less than 5 years of age. The mean (±SD) age at dispersal was 5.28±2.80 years. Of the 50 males that remained in their natal groups, 11 bred to produce 83 infants, which is about 55% of all infants born to known sires and 79% of infants produced by captive-born males. A large percentage of infants in the few productive groups were likely to be produced by relatives.

Indian living population as of 2018

The Indian population, as of 2018, comprised 51 individuals (21 males, 24 females, 6 unknown sex) distributed across 10 zoos (see Sliwa & Begum, 2019). There are only four zoos with breeding units that comprise five or more individuals. The remaining six zoos keep units with fewer than three individuals, sometimes even one individual only.

The population consists of 16 wild-born (5 males, 11 females) and 34 captive-born individuals (15 males, 13 females, 6 unknown sex), as well as one individual of unknown origin. Wild-born individuals are housed in seven institutions, of which two zoos house lone individuals and two zoos house pairs (Table 9).

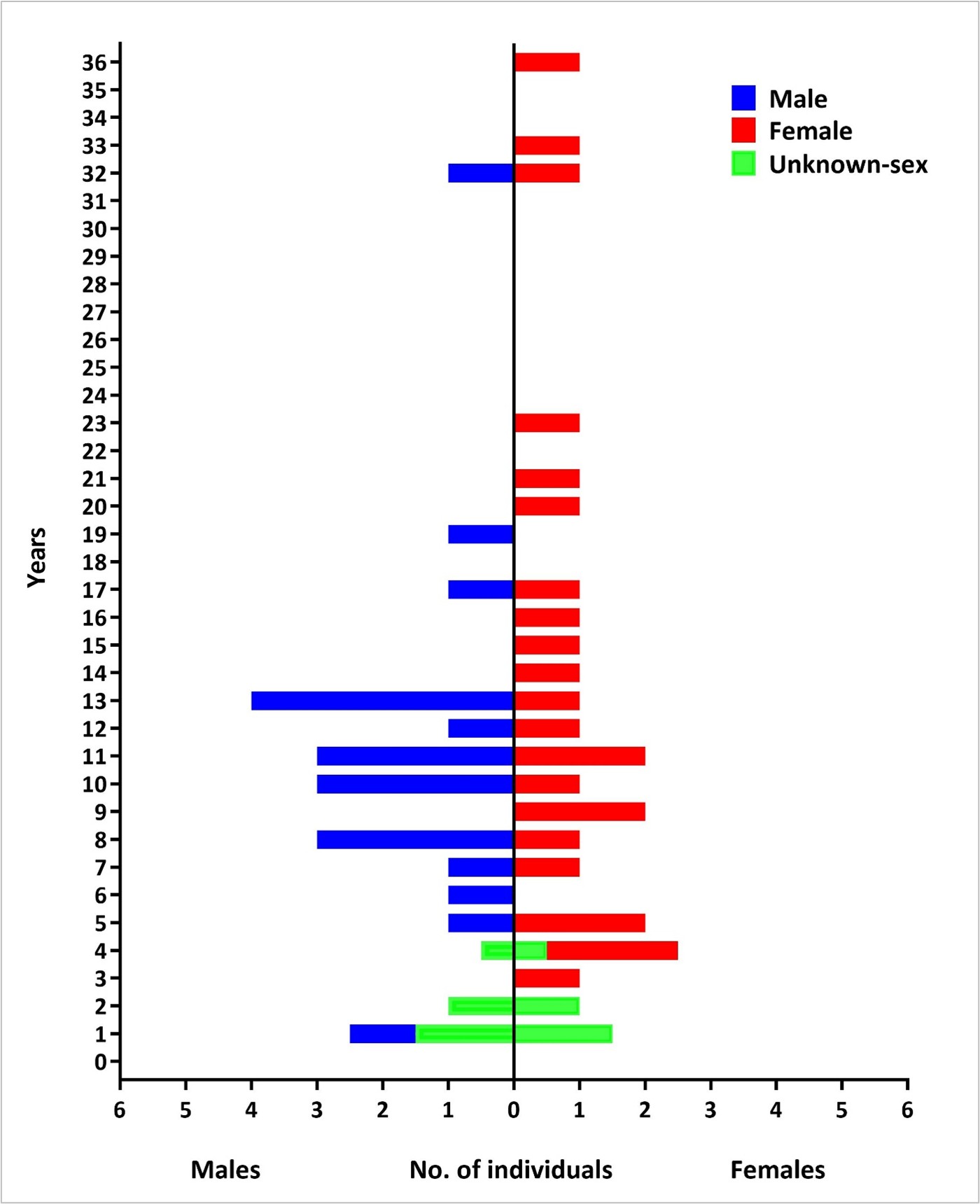

Age-sex composition

The age sex structure of the Indian population, as of 2018 refers to 51 individuals, including five individuals for whom birth date estimates were not known, but transfer dates to zoos were available (Figure 11). Based on these dates, the mean (±SD) ages of the individuals were as follows: females 14.65±9.2 years, males 11.8±6.12 years, unknown-sex 2.36±1.25 years.

The declining population trend and decreasing number of births are reflected in the unfavourable age-sex composition. As of 2018, there were only 10 individuals (1 male, 3 females, 6 unknown-sex) under the age of 5 years, accounting for about 19% of the population. Another 67% (n = 34; 19 males, 15 females) of the population was between the age range of 5 and 20 years, indicating some potential to breed, while 14% (n = 7; 1 male, 6 females) of the population was older than 20 years. With only a few individuals in the youngest age classes, the potential for future growth may be limited.

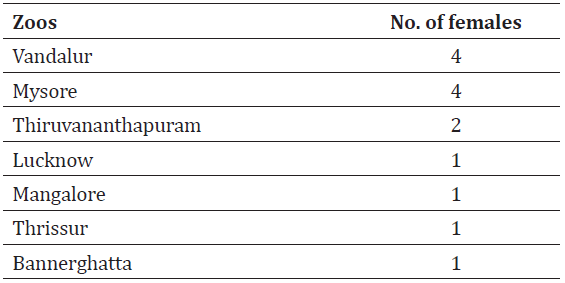

Seven zoos housed 14 females of breeding age (Table 10). Among the remaining three housing institutions, Delhi has a female under 5 years of age, who may breed in the future. Only two zoos have more than two females of breeding age. Furthermore, two zoos each house a single female of breeding age, and two other zoos maintain only pairs (see also Table 9).

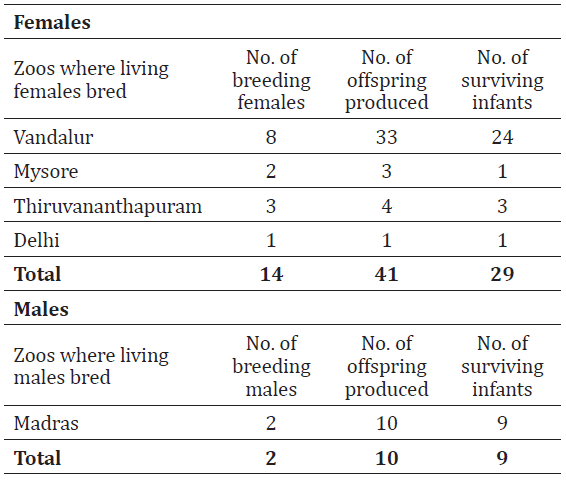

Reproduction in the living population

A total of 16 (2 males, 14 females) individuals in the living population as of 2018 bred in four institutions (Table 11). Females from only one zoo (Vandalur) contribute to approximately 83% of the surviving infants. Furthermore, there are no living sires in other zoos.

The females in the population (living in 2018) produced a total of 41 infants, of which 29 survived to the age of one year. In terms of reproductive output per female, 9 out of the 14 breeding females had two or fewer surviving infants. About 36% (n = 8) of the females that reached adulthood were yet to breed (see Table 12). Among the 14 females that had bred, five were over 20 years of age. The average age of the remaining nine breeding females was 11.62 ±3.68 years, with an age range of 5–17 years. Additionally, four of these nine females had not bred in the last 5 to 8 years. In contrast, four females housed in Vandalur had bred regularly, producing 3 to 4 offspring per female at intervals of 1 to 2 years. They produced 13 infants, of which 11 survived.

The differences in the number of infants produced by the females are even more pronounced in the males. Only two males (c.9.5%) contributed to breeding, resulting in nine surviving infants (Table 13).

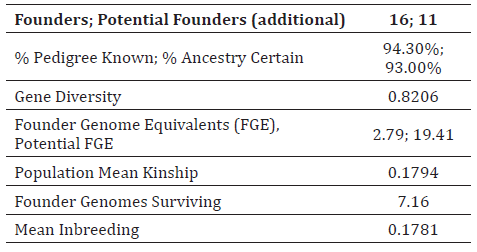

Genetic status

Since a future use of the population as a breeding and reserve population will require information on the living population’s (in 2018) genetic status, it is briefly presented here (Table 14 ) together with the potential of the members of the population for breeding, e.g., with reference to age.

The development of the genetic status is influenced by the fact that 77% of the individuals in the population did not breed at all. This includes 79% of wild-born and 76% of captive-born individuals. Among those that did breed, there was considerable variation in lifetime reproductive output, especially among the males. This pattern is consistent across generations and among both wild and captive-born individuals. Low productivity and large variation in reproductive success also go together with the small number of founders (n = 16) from which the living population is derived, and their uneven contributions to the gene pool.

Figure 9: Female transfers and reproductive output of captive lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos.

Figure 10: Male transfers and reproductive output of captive lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos.

The only living wild-caught individuals in the global captive population are in the Indian zoos. There were four founders and 12 potential founders (wild-born individuals with no living descendants) in the living population (as of 2018). The average age of the founders was 19.77±9.39 years, and the average age of the potential founders was 16.29±9.48 years. Twelve wild-born individuals were less than 20 years of age; however, their breeding potential, in terms of social living conditions, needs to be assessed. For example, two potential founder females were housed alone in two zoos.

Figure 11: Age-sex composition of the captive lion-tailed macaque population in India as of 2018

Table 9: Living population of captive lion-tailed macaques in India as of 2018.

Table 10: Distribution of captive lion-tailed macaque females aged 5-20 years (in 2018), in different zoos in India.

Table 11: Location of living breeders (in 2018) in the captive lion-tailed macaque population in Indian zoos.

Overall, the population retained 82.06% of gene diversity, which was lower than the recommended 90% for a captive population to be of conservation value (Soulé et al., 1986; Ballou et al., 2010). Moderate levels of relatedness among the individuals are reflected in the values of mean kinship (0.1794) and mean inbreeding (0.1781) (see Ballou et al., 2010). The values of most of the genetic measures indicate a low potential of the population as a reserve, also at the level of genetics (see Lees & Wilcken, 2009; Leus et al., 2011; Long et al., 2011; Che Castaldo et al., 2019).

Summary and conclusions

India only served as a resource for wild-caught lion-tailed macaques for American and European zoos in the first decades of the 20th century. The history of an Indian captive population of the species in zoos started in the 1950s, characterised by local management only, and a distribution over many zoos keeping few individuals only. Breeding occurred rarely. From the total of about 500 wild-caught lion-tailed macaques, almost equal proportions of individuals went to North America, Europe, and remained in India. They grew over the next decades in subpopulations of different sizes and composition: peak sizes were 269 (1988) in North America, 338 (2012) in Europe, 80 (2014) in Japan, and 76 (1988) in India. The living populations as of 2018 comprised 31 individuals in North America, 322 in Europe, 76 in Japan, and 51 in India.

The development of the subpopulations was influenced by different (systematic) management approaches as realised within breeding programmes. They were established in 1983 (North America), 1989 (Europe), and in the 2000s (India). The programmes in India differ from the SSP and the EEP version in terms of a strictly designed and controlled system managed by a “Central Zoo Authority”. The nature of the breeding programme provides only a limited influence of local zoo staff, although they are directly dealing with the animals.

Table 12: Individual reproductive output of the females in the living population of the captive lion-tailed macaque in India as of 2018.

Table 13: Individual reproductive output of the males in the living population of the captive lion-tailed macaque in India as of 2018.

Whereas SSP and EEP intend to include all individuals kept in the region in question (e.g., in North America or Europe) in the programme, in India, only a small proportion of the zoos and individuals, respectively, are included. For the lion-tailed macaque, the breeding programme presently comprises only three out of the 10 housing institutions.

Table 14: Genetic status of the Indian population of captive lion-tailed macaque (in 2018) as provided by PMx.

The productivity of the Indian lion-tailed macaque population was low due to poor breeding conditions, and especially due to a low number of potentially productive females in species-typical breeding units and appropriate enclosures. According to Singh et al. (2006), a female lion-tailed macaque in the wild may give birth to up to five infants during her lifetime, but infants have a high survivorship rate. Field studies show that infant survivorship rate in the wild ranges from 0.80 to 0.973 (Kumar, 1987, 1995; Sharma, 2002; Krishna et al., 2006). Our study reveals that in the Indian historical captive population, 68% of the females did not breed, and 26% of the infants born either died or were lost to follow-up within the first year of life. Among the captive females that reproduced, most had fewer than five infants, with 45% producing only 1–2 infants per female lifetime. Evidently, the productivity of the females is low. As was found in the global captive population (Begum et al., 2022, 2023), a large percentage of the females did not breed at all – a pattern that has not been reported from the wild. Overall, the living and breeding conditions do not consider and allow for the realisation of the social and reproductive system of lion-tailed macaques. The Indian population is still (too) small and has an unfavourable age-sex composition. It does not have the potential to grow significantly and to develop sustainability. In the past, it depended on the integration of wild-caught individuals. With reference to the biology of lion-tailed macaques for successful breeding, larger groups with female-bonded structures are needed. To be able to carry out species-typical spacing patterns, groups would require large enclosures with some natural vegetation and richly furnished structures. Small night quarters in which lion-tailed macaques are kept for large parts of 24 hours of the day should be avoided. Under natural climatic conditions, safety during the night can also be realised via larger, airy subdivisions of the enclosures. Improved living conditions would increase the contribution of India to the global population growth via captive breeding. It has been low so far with 185 births, i.e., 8.5% of total global births. Overall, the structure of the units in which the lion-tailed macaques were kept in various zoos did not correspond to the social system of the species and especially to the demographic structure of the groups in which they are found in the wild. Besides others, this includes the option to have long-term social relationships and the conditions to develop species-typical socialisation patterns. For the management of the Indian subpopulation, consideration of the social system of the species is of utmost importance for the development of a national management plan.

With reference to the actual number of lion-tailed macaques in the ten zoos that keep the species, only three zoos have the potential to contribute to breeding in terms of group size and the resulting social conditions. Seven institutions (in 2018) kept single or two individuals only – a setup that does not consider the natural (social) way of living of the species and animal welfare standards. As far as possible, small groups should be formed with these individuals. The process, however, would require highly professional management since there are no such group formations under natural conditions, and the individuals involved might have developed behavioural deficiencies during their suboptimal living conditions. For details on the process of group formation and social integration under captive conditions, see Kaumanns et al. (2006).

The three groups (with > 5 individuals) in zoos that participate in the breeding programme may have the potential to contribute to further breeding; however, as a starting set for a reserve population, they do not provide enough individuals. The groups, furthermore, are slightly inbred. Their further use requires exchanges of breeding males.

The poor status of the Indian population requires the integration of further lion-tailed macaques from Europe– preferably (small) groups of related females. They should be associated with wild-born males in India. To realise this, a programme to achieve appropriate living and management conditions in Indian zoos that intend to keep lion-tailed macaques must be developed. This would include an assessment of existing keeping conditions, proposing improvements, designing new keeping systems, and developing an appropriate conservation breeding programme. The latter must consider international standards. As a key component of a new approach, management by a competent zoo biologist or veterinarian as a programme coordinator is required. The person should be familiar with the biology of the species, be an experienced practitioner in husbandry and management, and be able to act in a responsible way. Management decisions should be in his/her responsibilities but discussed and supported by a committee of representatives of the participating zoos. The latter would help to consider local husbandry systems and problems. This approach proved to be successful in the European breeding programme (EEP) as experienced by the second author, who acted as the founding and long-term coordinator for the EEP for the lion-tailed macaque. It welcomes external scientific advisors, e.g., field biologists. The quality of the work might be evaluated by experts who form a central zoo advisory board. On all levels, the use of scientific methods and knowledge is necessary. Contacts and know-how transfer with the relevant representatives and organisations of the scientific community are indicated. To establish such structures and to find the experts needed will be difficult in India since its zoo community and organisation so far does not support a more decentralised system that depends more on the responsibility of the individual zoos and their staff. The latter would be a condition for the development of professional expertise (see Singh et al., 2012). It is essential to consider that as many – better all – members of a zoo population of a species, in this case lion-tailed macaque, are included and managed in a programme like it is propagated in the European breeding programmes. In the case of the Indian population of the lion-tailed macaque, coordination should be attempted to fully integrate all 51 individuals into a management plan and to interact with the European breeding programme to establish a population as proposed above.

Although the status of the captive population in Indian zoos is poor and might be difficult to improve towards a reserve population, efforts to achieve this goal are critical for the survival of the global captive population. Programmes for the reintroduction of this threatened primate species – endemic to South India – evidently must be realised via Indian zoos. To serve as an interface, they must develop the necessary expertise, keeping systems and a viable national captive population. The Indian community of conservation biologists seems to be motivated to support corresponding plans, as indicated by several publications (see Singh et al., 2012; Kaumanns et al., 2013; Begum et al., 2021).

The analysis of the Indian population intends to contribute to the development of better global and national programmes. This study also demonstrates the special need for the existing international breeding programmes in the various regions to consider and care for the captive population of the species in its country of origin. Plans to transfer lion-tailed macaques and to improve the living conditions, training and know-how transfer for Indian zoos have not been materialised, consequently, and over longer time periods since the first international conference on lion-tailed macaques in zoos in Baltimore in 1982 (see Singh et al., 2009).

The present study indicates very poor reproductive output of the Indian population, and related to this is a likely loss of genetic and phenotypic diversity. Therefore, the Indian captive population so far cannot be considered as a potential reserve. This is supported by the poor age-sex composition of the current population, especially due to the old age of the wild-born individuals. Furthermore, many females experience long periods of non-breeding. Living conditions that do not allow reproduction for extended time periods might negatively impact the future reproductive potential of individuals (see Penfold et al., 2014).

The finding that there are two genetically different subpopulations of the lion-tailed macaque in the wild (Ram et al., 2015) has not yet been properly considered for the global captive populations. The authors propose to treat the two genetic types as separate conservation units. Ram et al. (2015) found that most of the members of the Indian captive population are of the southern and a few of the northern type. A genetic analysis would be urgently needed for the European population.

All living wild-born lion-tailed macaques of the global captive population are kept in Indian zoos (Sliwa & Begum, 2019). This must be considered for the management of the global population.

The present study can be regarded as a model study that highlights the problems and management issues in a population of a highly threatened animal species. It can be used as a model for the analysis of captive populations for other primates and other threatened mammal species. Inappropriate living conditions and management in the past of a population decrease its potential to serve as a reserve. It refers to the adaptive potential of the species in question. The adaptive potential of a species kept in zoos should be regarded as a key aspect of conservation breeding (see Kaumanns et al., 2020, 2025).

Acknowledgement

Nilofer Begum, Werner Kaumanns and Mewa Singh thank Prof. Dr. Hans-Jürg Kuhn, former Director of German Primate Center, Göttingen; late Prof. Dr. Gunther Nogge, former Director of Cologne Zoo; Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer, former Director of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, Berlin; and Dr. Alexander Sliwa, former EEP Coordinator for the lion-tailed macaque, Cologne Zoo, for supporting the Lion-tailed macaque project. Mewa Singh thanks the Indian National Science Academy for the Distinguished Professor award, during which this article was prepared.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Werner Kaumanns & Mewa Singh hold editorial positions at the Journal of Wildlife Science. However, they did not participate in the peer review process of this article except as authors. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data used in the study is available in Sliwa & Begum (2019).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

NB and WK conceptualised the idea and wrote the manuscript; data analysis has been done by NB. All authors contributed to the discussion and the finalisation of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version.

Edited By

Honnavalli Kumara

Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Tamil Nadu.

*CORRESPONDENCE

Nilofer Begum

✉ niloferbegum3@gmail.com

CITATION

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W. & Singh, M. (2025). Lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos in the context of the global population. Journal of Wildlife Science, 2(4), 114-126. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.CXGU6570

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Begum, Kaumanns & Singh. This is an open access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The information contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ballou, J. D., Lees, C., Faust, L. J., Long, S., Lynch, C., Lackey, L. B. & Foose, T. J. (2010). Demographic and genetic management of captive populations. In: Kleiman, D. G., Thompson, K. & Baer C. K. (eds.), Wild mammals in captivity: Principles and techniques for zoo management. University of Chicago Press. pp.219–252.

Ballou, J. D., Lacy, R. C., Pollak, J. P., Callicrate, T. & Ivy, J. (2025). PMx: Software for demographic and genetic analysis and management of pedigreed populations (Version 1.8.1.20250501). Chicago Zoological Society, Brookfield, Illinois, USA. http://www.scti.tools

Begum, N. (2023). Primates under altered living conditions: Development and conservation potential of the captive lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus population. PhD Thesis, Freie Universität Berlin. https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/handle/fub188/39329

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W., Sliwa, A. & Singh, M. (2021). The captive population of the lion- tailed macaque Macaca silenus. The future of an endangered primate under human care. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 13(9), 19352–19357. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.7521.13.9.19352-19357

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W., Singh, M. & Hofer, H. (2022). A hun¬dred years in zoos: History and development of the captive population of the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus. Long term persistence for conservation? Primate Conservation, 36, 155–172. http://www.primate-sg.org/storage/pdf/PC36_Begum_et_al_100_years_captive_lion-tail_macaques.pdf

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W., Hofer, H. & Singh, M. (2023). A hun¬dred years in zoos II: Patterns of reproduction in the global historical captive population of the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus. Primate Conservation, 37, 134–154. http://www.primate-sg.org/storage/pdf/PC37

Central Zoo Authority. (2011). Guidelines/ norms for conservation breeding programme of the Central Zoo Authority. Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi. p.4 https://cza.nic.in/uploads/documents/CBP/Guidelines%20for%20the%20CBP.pdf

Che-Castaldo, J., Johnson, B., Magrisso, N., Mechak, L., Melton, K., Mucha, K., Terwilliger, L., Theis, M., Long, S. & Faust, L. (2019). Patterns in the long-term viability of North American zoo populations. Zoo Biology, 38(1), 78–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21471

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). (2025). CITES Appendices I, II and III valid from 7 February 2025. https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php

Dhawale, A. K. & Sinha, A. (2025). Population dynamics of a lion‐tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) population in a rainforest fragment in the southern Western Ghats of India. American Journal of Primatology, 87(9), e70075. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.70075

GraphPad Software. (2025). GraphPad Prism (Version 10.6.0 for Windows). Boston, Massachusetts, USA. https://www.graphpad.com/

Heltne, P. G. (ed.), (1985). The Lion-tailed macaque: Status and conservation. Alan R. Liss.

Hill, C. A. (1971). Zoo’s help for a rare monkey. Oryx, 11(1), 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003060530000942X

Kaumanns, W. & Rohrhuber, B. (1995). Captive propagation in lion-tailed macaques: The status of the European population and research implications. In: Gansloßer, U., Hodges, J. K. & Kaumanns, W. (eds.), Research and Captive Propagation, Filander Verlag. pp.296–309.

Kaumanns, W., Schwitzer, C., Schmidt, P. & Knogge, C. (2001). The European lion-tailed macaque population: An overview. Primate Report, 59, 65–76.

Kaumanns, W., Krebs, E. & Singh, M. (2006). An endangered species in captivity: Husbandry and management of the lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus). MyScience, 1(1), 43–71.

Kaumanns, W., Singh, M. & Sliwa, A. (2013). Captive propagation of threatened primates – the example of the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 5(14), 4825–4839. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o3625.4825-39

Kaumanns, W., Begum, N. & Hofer, H. (2020). Animals are designed for breeding: Captive population management needs a new perspective. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, 8(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v8i2.477

Kaumanns, W., Begum, N. & Singh, M. (2025). Wild animals in zoos: A new paradigm is needed for zoos in the future. Journal of Wildlife Science, 2(3), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.IFNA7720

Kavana, T. S., Mohan, K., Erinjery, J. J., Singh, M. & Kaumanns, W. (2025). Distribution and habitat suitability of the endangered lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus and other primate species in the Kodagu region of the Western Ghats, India. Primates, 66(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-024-01152-6

Krishna, B. A., Singh, M. & Singh, M. (2006). Population dynamics of a group of lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) inhabiting a rainforest fragment in the Western Ghats, India. Folia Primatologica, 77(5), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1159/000093703

Kumar, A. (1987). The ecology and population dynamics of the lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) in south India. PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge.

Kumar, A. (1995). Birth rate and survival in relation to group size in the lion-tailed macaques, Macaca silenus. Primates, 36(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02381911

Kumar, M. A., Singh, M., Kumara, H. N., Sharma, A. K. & Bertsch, C. (2001). Male migration in lion-tailed macaques. Primate Report, 59, 5–18.

Kumara, H. N. & Singh, M. (2004). Distribution and abundance of primates in rainforests of the Western Ghats, Karnataka, India and the conservation of Macaca silenus. International Journal of Primatology, 25(5), 1001–1018. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IJOP.0000043348.06255.7f

Kumara, H. N. & Sinha, A. (2009). Decline of the endangered lion-tailed macaque, Macaca silenus, in the Western Ghats, India. Oryx, 43(2), 292–298. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605307990900

Kumara, H. N., Sasi, R., Suganthasakthivel, R., Singh, M., Sushma, H. S., Ramachandran, K. K. & Kaumanns, W. (2014). Distribution, demography, and conservation of lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) in the Anamalai Hills landscape, Western Ghats, India. International Journal of Primatology, 35(5), 976–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-014-9776-2

Lees, C. M. & Wilcken, J. (2009). Sustaining the Ark: The challeng¬es faced by zoos in maintaining viable populations. International Zoo Yearbook, 43(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1090.2008.00066.x

Leus, K., Lackey, L. B., van Lint, W., de Man, D., Riewald, S., Veld¬kam, A. & Wijmans, J. (2011). Sustainability of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria bird and mammal populations. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums Magazine, 12, 11–14.

Lindburg, D. G., Iaderosa, J. & Gledhill, L. (1997). Steady-state propagation of captive lion-tailed macaques in North American zoos: A conservation strategy. In: Wallis, J. (ed.), Primate Conservation: The Role of Zoological Parks, Special Topics in Primatology, 1. American Society of Primatologists. pp.131–149.

Lindburg, D. G. (2001). A century of involvement with lion-tailed macaques in North America. Primate Report, 59, 51–64.

Long, S., Dorsey, C. & Boyle, P. (2011). Status of Association of Zoos and Aquariums cooperatively managed populations. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums Magazine, 12, 15–18.

Mallapur, A., Waran, N. & Sinha, A. (2005a). Factors influencing the behaviour and welfare of captive lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 91(3-4), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2004.10.002

Mallapur, A., Waran, N. & Sinha, A. (2005b). Use of enclosure space by captive lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) housed in Indian zoos. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 8(3), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327604jaws0803_2

Molur, S., Brandon-Jones, D., Dittus, W., Eudey, A., Kumar, A., Singh, M., Feeroz, M. M., Chalise, M., Priya, P. & Walker, S. (2003). Status of South Asian primates: Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (C.A.M.P.). Workshop Report 2003, Zoo Outreach Organization/CBSG-South Asia, Coimbatore. https://zooreach.org/downloads/ZOO_CAMP_PHVA_reports/2003PrimateReport.pdf

Penfold, L. M., Powell, D., Traylor-Holzer, K. & Asa, C. S. (2014). 'Use it or lose it': Characterization, implications, and mitigation of female infertility in captive wildlife. Zoo Biology, 33(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21104

Ram, M. S., Marne, M., Gaur, A., Kumara, H. N., Singh, M., Kumar, A. & Umapathy, G. (2015). Pre-historic and recent vicariance events shape genetic structure and diversity in endangered lion-tailed

macaque in the Western Ghats: Implications for conservation. PLOS ONE, 10, e0142597. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142597

Ramachandran, K. K. & Joseph, G. K. (2000). Habitat utilization of lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) in Silent Valley National Park, Kerala, India. Primate Report, 58, 17–25.

R Core Team. (2025). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Rode-White, G. & Corlay, M. (2024). Long-term management plan for the lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) European Endangered Species Programme (EEP). Zoologischer Garten Köln, Köln, Germany and European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), Amsterdam, Netherlands. p.17.

Scobie, P. & Bingaman Lackey, L. (2012). Single Population Analysis and Records Keeping System (SPARKS) (Version 1.66). International Species Information System (ISIS), renamed to Species360. Minnesota, USA.

Sharma, A. K. (2002). A study of the reproductive behaviour of lion tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) in the rainforests of Western Ghats. PhD Thesis, University of Mysore.

Singh, M. & Kaumanns, W. (2005). Behavioural studies: A necessity for wildlife management. Current Science, 89(7), 1230–1236. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24110976

Singh, M., Sharma, A. K., Krebs, E. & Kaumanns, W. (2006). Reproductive biology of lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus): An important key to the conservation of an endangered species. Current Science, 90(6), 804–811. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24089192

Singh, M., Kaumanns, W., Singh, M., Sushma, H. S. & Molur, S.(2009). The lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus (Primates: Cercopithecidae): Conservation history and status of a flagship species of the tropical rainforests of the Western Ghats, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 1(3), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o2000.151-7

Singh, M., Kaumanns, W., & Umapathy, G. (2012). Conservation-oriented captive breeding of primates in India: Is there a perspective? Current Science, 103(12), 1399–1400. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24089343

Singh, M. (2019). Management of forest-dwelling and urban spe¬cies: Case studies of the lion- tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) and the bonnet macaque (M. radiata). International Journal of Primatology, 40(6), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-019-00122-w

Singh, M., Kumar, A. & Kumara, H. N. (2020). Macaca silenus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T12559A17951402. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12559A17951402.en

Sliwa, A., Schad, K. & Fienig, E. (2016). Long-term management plan for the lion tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) European Endangered Species Programme (EEP). Zoologischer Garten Köln, Köln, Germany and European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), Amsterdam, Netherlands. p.60

Sliwa, A. & Begum, N. (2019). International studbook 2018 for the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus Linnaeus, 1758, (Edition 2018, Volume 9). Zoologischer Garten Köln, Köln, Germany.

Soulé, M., Gilpin, M., Conway, W. & Foose, T. (1986). The millenium ark: How long a voyage, how many staterooms, how many passengers? Zoo Biology, 5(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.1430050205

Sushma, H. S., Mann, R., Kumara, H. N. & Udhayan, A. (2014). Population status of the endangered lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus in Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Western Ghats, India. Primate Conservation, 28(1), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1896/052.028.0120

Edited By

Honnavalli Kumara

Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Tamil Nadu.

*CORRESPONDENCE

Nilofer Begum

✉ niloferbegum3@gmail.com

CITATION

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W. & Singh, M. (2025). Lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos in the context of the global population. Journal of Wildlife Science, 2(4), 114-126. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.CXGU6570

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Begum, Kaumanns & Singh. This is an open access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The information contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ballou, J. D., Lees, C., Faust, L. J., Long, S., Lynch, C., Lackey, L. B. & Foose, T. J. (2010). Demographic and genetic management of captive populations. In: Kleiman, D. G., Thompson, K. & Baer C. K. (eds.), Wild mammals in captivity: Principles and techniques for zoo management. University of Chicago Press. pp.219–252.

Ballou, J. D., Lacy, R. C., Pollak, J. P., Callicrate, T. & Ivy, J. (2025). PMx: Software for demographic and genetic analysis and management of pedigreed populations (Version 1.8.1.20250501). Chicago Zoological Society, Brookfield, Illinois, USA. http://www.scti.tools

Begum, N. (2023). Primates under altered living conditions: Development and conservation potential of the captive lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus population. PhD Thesis, Freie Universität Berlin. https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/handle/fub188/39329

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W., Sliwa, A. & Singh, M. (2021). The captive population of the lion- tailed macaque Macaca silenus. The future of an endangered primate under human care. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 13(9), 19352–19357. https://doi.org/10.11609/jott.7521.13.9.19352-19357

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W., Singh, M. & Hofer, H. (2022). A hun¬dred years in zoos: History and development of the captive population of the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus. Long term persistence for conservation? Primate Conservation, 36, 155–172. http://www.primate-sg.org/storage/pdf/PC36_Begum_et_al_100_years_captive_lion-tail_macaques.pdf

Begum, N., Kaumanns, W., Hofer, H. & Singh, M. (2023). A hun¬dred years in zoos II: Patterns of reproduction in the global historical captive population of the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus. Primate Conservation, 37, 134–154. http://www.primate-sg.org/storage/pdf/PC37

Central Zoo Authority. (2011). Guidelines/ norms for conservation breeding programme of the Central Zoo Authority. Central Zoo Authority, New Delhi. p.4 https://cza.nic.in/uploads/documents/CBP/Guidelines%20for%20the%20CBP.pdf

Che-Castaldo, J., Johnson, B., Magrisso, N., Mechak, L., Melton, K., Mucha, K., Terwilliger, L., Theis, M., Long, S. & Faust, L. (2019). Patterns in the long-term viability of North American zoo populations. Zoo Biology, 38(1), 78–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21471

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). (2025). CITES Appendices I, II and III valid from 7 February 2025. https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php

Dhawale, A. K. & Sinha, A. (2025). Population dynamics of a lion‐tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) population in a rainforest fragment in the southern Western Ghats of India. American Journal of Primatology, 87(9), e70075. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.70075

GraphPad Software. (2025). GraphPad Prism (Version 10.6.0 for Windows). Boston, Massachusetts, USA. https://www.graphpad.com/

Heltne, P. G. (ed.), (1985). The Lion-tailed macaque: Status and conservation. Alan R. Liss.

Hill, C. A. (1971). Zoo’s help for a rare monkey. Oryx, 11(1), 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003060530000942X

Kaumanns, W. & Rohrhuber, B. (1995). Captive propagation in lion-tailed macaques: The status of the European population and research implications. In: Gansloßer, U., Hodges, J. K. & Kaumanns, W. (eds.), Research and Captive Propagation, Filander Verlag. pp.296–309.

Kaumanns, W., Schwitzer, C., Schmidt, P. & Knogge, C. (2001). The European lion-tailed macaque population: An overview. Primate Report, 59, 65–76.

Kaumanns, W., Krebs, E. & Singh, M. (2006). An endangered species in captivity: Husbandry and management of the lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus). MyScience, 1(1), 43–71.

Kaumanns, W., Singh, M. & Sliwa, A. (2013). Captive propagation of threatened primates – the example of the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 5(14), 4825–4839. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o3625.4825-39

Kaumanns, W., Begum, N. & Hofer, H. (2020). Animals are designed for breeding: Captive population management needs a new perspective. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, 8(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v8i2.477

Kaumanns, W., Begum, N. & Singh, M. (2025). Wild animals in zoos: A new paradigm is needed for zoos in the future. Journal of Wildlife Science, 2(3), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.IFNA7720

Kavana, T. S., Mohan, K., Erinjery, J. J., Singh, M. & Kaumanns, W. (2025). Distribution and habitat suitability of the endangered lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus and other primate species in the Kodagu region of the Western Ghats, India. Primates, 66(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-024-01152-6

Krishna, B. A., Singh, M. & Singh, M. (2006). Population dynamics of a group of lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) inhabiting a rainforest fragment in the Western Ghats, India. Folia Primatologica, 77(5), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1159/000093703

Kumar, A. (1987). The ecology and population dynamics of the lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) in south India. PhD Thesis, University of Cambridge.

Kumar, A. (1995). Birth rate and survival in relation to group size in the lion-tailed macaques, Macaca silenus. Primates, 36(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02381911

Kumar, M. A., Singh, M., Kumara, H. N., Sharma, A. K. & Bertsch, C. (2001). Male migration in lion-tailed macaques. Primate Report, 59, 5–18.

Kumara, H. N. & Singh, M. (2004). Distribution and abundance of primates in rainforests of the Western Ghats, Karnataka, India and the conservation of Macaca silenus. International Journal of Primatology, 25(5), 1001–1018. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IJOP.0000043348.06255.7f

Kumara, H. N. & Sinha, A. (2009). Decline of the endangered lion-tailed macaque, Macaca silenus, in the Western Ghats, India. Oryx, 43(2), 292–298. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605307990900

Kumara, H. N., Sasi, R., Suganthasakthivel, R., Singh, M., Sushma, H. S., Ramachandran, K. K. & Kaumanns, W. (2014). Distribution, demography, and conservation of lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) in the Anamalai Hills landscape, Western Ghats, India. International Journal of Primatology, 35(5), 976–989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-014-9776-2

Lees, C. M. & Wilcken, J. (2009). Sustaining the Ark: The challeng¬es faced by zoos in maintaining viable populations. International Zoo Yearbook, 43(1), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-1090.2008.00066.x

Leus, K., Lackey, L. B., van Lint, W., de Man, D., Riewald, S., Veld¬kam, A. & Wijmans, J. (2011). Sustainability of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria bird and mammal populations. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums Magazine, 12, 11–14.

Lindburg, D. G., Iaderosa, J. & Gledhill, L. (1997). Steady-state propagation of captive lion-tailed macaques in North American zoos: A conservation strategy. In: Wallis, J. (ed.), Primate Conservation: The Role of Zoological Parks, Special Topics in Primatology, 1. American Society of Primatologists. pp.131–149.

Lindburg, D. G. (2001). A century of involvement with lion-tailed macaques in North America. Primate Report, 59, 51–64.

Long, S., Dorsey, C. & Boyle, P. (2011). Status of Association of Zoos and Aquariums cooperatively managed populations. World Association of Zoos and Aquariums Magazine, 12, 15–18.

Mallapur, A., Waran, N. & Sinha, A. (2005a). Factors influencing the behaviour and welfare of captive lion-tailed macaques in Indian zoos. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 91(3-4), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2004.10.002

Mallapur, A., Waran, N. & Sinha, A. (2005b). Use of enclosure space by captive lion-tailed macaques (Macaca silenus) housed in Indian zoos. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 8(3), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327604jaws0803_2

Molur, S., Brandon-Jones, D., Dittus, W., Eudey, A., Kumar, A., Singh, M., Feeroz, M. M., Chalise, M., Priya, P. & Walker, S. (2003). Status of South Asian primates: Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (C.A.M.P.). Workshop Report 2003, Zoo Outreach Organization/CBSG-South Asia, Coimbatore. https://zooreach.org/downloads/ZOO_CAMP_PHVA_reports/2003PrimateReport.pdf

Penfold, L. M., Powell, D., Traylor-Holzer, K. & Asa, C. S. (2014). 'Use it or lose it': Characterization, implications, and mitigation of female infertility in captive wildlife. Zoo Biology, 33(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.21104

Ram, M. S., Marne, M., Gaur, A., Kumara, H. N., Singh, M., Kumar, A. & Umapathy, G. (2015). Pre-historic and recent vicariance events shape genetic structure and diversity in endangered lion-tailed

macaque in the Western Ghats: Implications for conservation. PLOS ONE, 10, e0142597. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142597

Ramachandran, K. K. & Joseph, G. K. (2000). Habitat utilization of lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) in Silent Valley National Park, Kerala, India. Primate Report, 58, 17–25.

R Core Team. (2025). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Rode-White, G. & Corlay, M. (2024). Long-term management plan for the lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) European Endangered Species Programme (EEP). Zoologischer Garten Köln, Köln, Germany and European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), Amsterdam, Netherlands. p.17.

Scobie, P. & Bingaman Lackey, L. (2012). Single Population Analysis and Records Keeping System (SPARKS) (Version 1.66). International Species Information System (ISIS), renamed to Species360. Minnesota, USA.

Sharma, A. K. (2002). A study of the reproductive behaviour of lion tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) in the rainforests of Western Ghats. PhD Thesis, University of Mysore.

Singh, M. & Kaumanns, W. (2005). Behavioural studies: A necessity for wildlife management. Current Science, 89(7), 1230–1236. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24110976

Singh, M., Sharma, A. K., Krebs, E. & Kaumanns, W. (2006). Reproductive biology of lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus): An important key to the conservation of an endangered species. Current Science, 90(6), 804–811. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24089192

Singh, M., Kaumanns, W., Singh, M., Sushma, H. S. & Molur, S.(2009). The lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus (Primates: Cercopithecidae): Conservation history and status of a flagship species of the tropical rainforests of the Western Ghats, India. Journal of Threatened Taxa, 1(3), 151–157. https://doi.org/10.11609/JoTT.o2000.151-7

Singh, M., Kaumanns, W., & Umapathy, G. (2012). Conservation-oriented captive breeding of primates in India: Is there a perspective? Current Science, 103(12), 1399–1400. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24089343

Singh, M. (2019). Management of forest-dwelling and urban spe¬cies: Case studies of the lion- tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) and the bonnet macaque (M. radiata). International Journal of Primatology, 40(6), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-019-00122-w

Singh, M., Kumar, A. & Kumara, H. N. (2020). Macaca silenus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T12559A17951402. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12559A17951402.en

Sliwa, A., Schad, K. & Fienig, E. (2016). Long-term management plan for the lion tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) European Endangered Species Programme (EEP). Zoologischer Garten Köln, Köln, Germany and European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA), Amsterdam, Netherlands. p.60

Sliwa, A. & Begum, N. (2019). International studbook 2018 for the lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus Linnaeus, 1758, (Edition 2018, Volume 9). Zoologischer Garten Köln, Köln, Germany.

Soulé, M., Gilpin, M., Conway, W. & Foose, T. (1986). The millenium ark: How long a voyage, how many staterooms, how many passengers? Zoo Biology, 5(2), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/zoo.1430050205

Sushma, H. S., Mann, R., Kumara, H. N. & Udhayan, A. (2014). Population status of the endangered lion-tailed macaque Macaca silenus in Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve, Western Ghats, India. Primate Conservation, 28(1), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1896/052.028.0120