TYPE: Research Article![]()

Mortality investigations in wild Asiatic elephants (Elephas maximus) due to infected Kodo millet consumption in Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh- A case study

Vijay Kumar N. Ambade¹, Subharanjan Sen¹, Lakshman Krishnamoorthy¹*![]() , Ramesh Kumar Pandey²

, Ramesh Kumar Pandey²![]() , Amit Kumar Dubey¹, Anupam Sahay¹, Prakash Kumar Varma¹, Ritesh Sarothiya¹, Shoba Jawre³, Nidhi Rajput³, Aniruddha Majumdar4

, Amit Kumar Dubey¹, Anupam Sahay¹, Prakash Kumar Varma¹, Ritesh Sarothiya¹, Shoba Jawre³, Nidhi Rajput³, Aniruddha Majumdar4![]() , Tejas Karmarkar¹, Harikishan Sudini5

, Tejas Karmarkar¹, Harikishan Sudini5![]() , Karikalan Mathesh6

, Karikalan Mathesh6![]() , Swati Shrivastav7, Nitin Gupta¹, Parag Nigam8

, Swati Shrivastav7, Nitin Gupta¹, Parag Nigam8![]()

¹Madhya Pradesh Forest Department, Bhopal, M.P. India

²Ministry of Environment and Forest and Climate Change, GoI, New Delhi

³School of Wildlife Forensic and Health, Nanaji Deshmukh Veterinary Science University, Jabalpur

4State Forest Research Institute- Jabalpur, M.P.

5International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, Hyderabad

6Indian Veterinary Research Institute, Bareilly, U.P.

7State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar, M.P.

8Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, Uttrakhand

RECEIVED 20 August 2025

ACCEPTED 24 November 2025

ONLINE EARLY 30 December 2025

Abstract

In October 2024, a significant mortality event involving ten wild Asiatic elephants (Elephas maximus) occurred in the Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve (BTR), Madhya Pradesh, India. This case study investigates the circumstances and causes underlying this incident, highlighting the emerging risks at the wildlife-agriculture interface. The affected elephants were part of a herd that had migrated from Chhattisgarh to BTR in recent years, demonstrating seasonal foraging behaviour in buffer zones and adjacent agricultural landscapes. Such interactions increase the chances of exposure to agricultural hazards, particularly during the periods of food scarcity.

Initial field assessments and post-mortem examinations conducted by a multidisciplinary team revealed no external trauma. However, generalised haemorrhages and significant gastrointestinal distension with undigested Kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum) were evident. Histopathological analysis showed systemic vascular and epithelial damage, including pulmonary oedema, hepatic necrosis, and renal tubular degeneration, all suggestive of acute toxicosis. Chemical Residue Analysis was conducted to test for chemical residues in crops. Toxicological screening was negative for conventional poisons such as organophosphates, pyrethroids, heavy metals, and cyanide. Molecular testing for elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV), a potential differential diagnosis, also returned negative for all individuals. Cyclo piazonic acid (CPA), a mycotoxin produced by Aspergillus and Penicillium species, was detected at lethal concentrations in elephant tissue and gastrointestinal contents. Environmental and crop samples from nearby fields also revealed CPA infestation. Fungal cultures from elephant gut content and crop residues confirmed the presence of CPA-producing fungi.

The event underscores the risks posed by mycotoxin contaminations in millets grown under high-moisture conditions, particularly during unseasonal rainfall. The findings carry substantial implications for wildlife health, conservation policy, and agricultural practices in shared landscapes. Recommendations include restricting high-risk crop cultivation near protected areas, enhancing post-harvest storage practices, implementing routine mycotoxin surveillance, and promoting farmer awareness. This case also calls for coordinated action across forestry, veterinary, and agricultural departments under a “One Health” approach to prevent such incidents in the future.

Keywords: Cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), fungal poisoning, millets, mycotoxicosis, Paspalum scrobiculatum.

Introduction

Globally, wild Asiatic elephants are present in 13 range countries, and India holds the largest population of wild Asian elephants (Elephas maximus indicus) with an estimated population of 27,312 animals (MoEF&CC, 2017). Asiatic elephants are extremely sociable, forming groups of six to seven related females led by the oldest female, the matriarch. More than two-thirds of an elephant’s day may be spent feeding on grasses, but it also eats large amounts of tree bark, roots, leaves, and small stems. Cultivated crops such as bananas, rice, pulses and sugarcane are the most preferred foods (Sukumar, 1990). Human habitation is impinging on the boundary of many protected areas, and seasonal overabundance of food crops adjoining elephant habitats may also attract elephants irrespective of forage availability inside forests (Panda et al. 2020).

State Forest Departments have implemented a range of site-specific and landscape-level interventions to prevent and mitigate human–elephant conflict across human-dominated landscapes. In Madhya Pradesh, these measures include the deployment of a mobile application (Gaj-Rakshak) for real-time tracking and alert dissemination of elephant movements in conflict-prone areas, GPS collaring of repeatedly conflict-involved elephants for continuous monitoring, and the installation of elephant-proof trenches and solar-powered fencing at strategic locations in and around Bandhavgarh and Sanjay–Dubri Tiger Reserves. Although many mitigation strategies are locally driven and provide short-term relief, several interventions have been effective in restricting elephant movement into human habitations and reducing conflict incidence.

The central Indian landscape, sprawling over 1,52,000 km2 encompassing Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Chhatisgarh, is considered the heart of India’s wildlife habitats. It is home to some of India’s largest forest tracts, rich wildlife, as well as indigenous people who have been living in the forests since time immemorial.: Historically, elephants were once abundant in Madhya Pradesh, but declined and disappeared by the early 20th century (Qureshi et al., 2025). In 2018, a herd of 40 elephants dispersed from Chhattisgarh into eastern Madhya Pradesh (Natarajan et al. 2023). The herd initially entered through the Panpatha buffer range, exploring various parts of Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve (BTR) before settling down. Forest Department closely monitored the elephants’ movements and behaviour, through tracking teams. Since then, the elephant population in BTR has increased to 60 (by year 2023), including five solitary bulls. These elephants show seasonal movement patterns, with the Panpatha buffer range and BTR serving as key habitats at different times of the year. These recent range expansions have heightened human-elephant interactions, raising concerns for both residents and forest officials.

On October 29, 2024, staff at BTR in Madhya Pradesh discovered a distressing incident. Four elephants were found dead in the Sankhani and Bakeli areas of the Khitoli range of BTR (23°45’20”N 80°55’28”E; Fig.1), while six others exhibited severe symptoms of illness. On October 30, four more elephants succumbed to death, followed by two additional fatalities on October 31, 2024. A total of 10 elephants died within two days.

Post-mortem findings consistently revealed large quantities of undigested Kodo millet in the stomachs of all 10 deceased elephants. Laboratory analyses revealed lesions in the heart, liver, kidney and spleen indicative of cardiac failure leading to passive venous congestion, hypoxia and resultant degenerative changes in the visceral organs. Additionally, the changes in the liver and kidney were indicative of acute toxicity. The toxicological analysis carried out on the samples were negative for common pesticides, heavy metals and hydrogen cyanide (HCN), but positive for cyclopiazonic acid (CPA). Details of the necropsies carried out, including laboratory (histopathological, haematology, and toxicology) examinations, are presented further in the result section of the article.

Elephants are known to be in negative interactions with humans causing “human-elephant conflict.” The most common forms of such conflict are crop-raiding (when elephants eat or destroycrops), property destruction, or simply people getting too close to elephants and triggering defensive behaviours that may lead to injury or death of people and elephants. Mortality of elephants due to Kodo millet consumption opens a new dimension of human-elephant conflict, which needs proper understanding for its further implications on elephant conservation. The main objective of this paper is to highlight this novel challenging issue for scientists and wildlife managers, and equip them to handle similar cases in future holistically.

Study area

Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve (23°30’–23°47′ N, 80°47’–81°11′ E) is located in the north-eastern part of Madhya Pradesh, the central India, along the northern slopes of the eastern Satpura range. It comprises two conservation units: Bandhavgarh National Park (448.8 km²) and Panpatha Wildlife Sanctuary (245.8 km²), with elevations ranging from 410 to 811 meters. The landscape includes rugged sandstone hills, densely forested valleys, and seasonal swamps. Bandhavgarh Hill, reaching 811 meters, lies at the reserve’s centre. Numerous seasonal streams traverse the area, eventually joining the Son river. Vegetation types include moist peninsular low-level Sal forest, northern dry mixed deciduous forest, dry deciduous scrub, dry grassland, and west Gangetic moist mixed deciduous forest (Champion & Seth, 1968).

BTR supports a variety of herbivores such as chital (Axis axis), sambar (Rusa unicolor), gaur (Bos gaurus), wild pig (Sus scrofa), barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak), and nilgai (Boselaphus tragocamelus), Asian elephant, along with primates like langurs (Semnopithecus entellus), rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), etc.

The region experiences a tropical climate with three distinct seasons: summer (March–June), monsoon (July–October), and winter (November–February). Temperature ranges from 2.2°C to 46°C. Over 80% of the annual rainfall occurs during the southwest monsoon (Sonakiya, 1993), while occasional northeast monsoon showers contribute minor precipitation during winter (Prakasam, 2006). Agriculture in villages surrounding BTR primarily involves paddy, Kodo millet, Kutki (Panicum sumatrense), and maize in the Kharif season (June to October), and wheat, chickpeas, and mustard in the Rabi season (October to June).

The incident of elephant mortality on October 29, 2024 occured near the Khitauli-Pataur core range boundary (23.75611° N, 80.9211° E), close to Salkhaniya revenue village (Figure 1). Preliminary observations revealed crop-raiding activity in Kodo millet fields the previous night, underscoring growing human–elephant conflict in the buffer zone (Figure 1).

Methodology for mortality investigations

On-site assessment

Upon notification of elephant mortality, a trained multi-disciplinary team comprising wildlife veterinarians, forest department officials, scientists from veterinary institutes, and wildlife biologists was mobilised to the site. The team conducted a preliminary assessment to secure the area and prevent human imprints. Further, GPS coordinates, ambient temperature, and weather conditions were also recorded (Figure 2).

Environmental cues suggestive of a possible cause of death, such as signs of poisoning or infectious diseases, were also recorded.

Post-mortem examination and sample collection

The post-mortem examination was conducted in accordance with standard guidelines for a systematic examination by the team of experts under the supervision of the Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife), Madhya Pradesh. All the biological samples were collected and stored in properly labelled, leak-proof containers with waterproof tags (Figure 3).

Figure1. Elephant mortality site at Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, M.P., India.

Figure 2. Field samples and data collection exercise after the elephant mortality incident at Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, India.

The biological samples were sent to the School of Wildlife Forensic and Health (SWFH), Nanaji Deshmukh Veterinary Science University, Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), Bareilly and State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar for histopathological and toxicological analyses and disease screening.

- For histopathological examination, tissue samples were collected from all the vital organs, including liver, kidney, heart, lungs, spleen, lymph nodes, stomach, intestines and tongue and fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and transported to the concerned laboratories.

- For toxicological examination, tissue samples of liver, kidney, spleen, heart, lungs, as well as stomach contents and intestinal contents were collected in sterile containers and preserved in saturated salt solutions for further dispatch to the concerned laboratories.

- For disease investigations, tissue samples as well as swab samples were collected for PCR and culture and preserved in RNA-DNA protector and transported to the designated laboratories under cold chain conditions.

- Environmental sampling: Samples from standing crops and harvested crops of Kodo and paddy were collected and labelled. Water samples were collected from all the all-adjacent existing waterholes near to the actual incident spot. For the collection of water samples, the research team had also considered the latest elephant movement record compared to the old record. Samples from water bodies were also collected and labelled. Kodo millet samples were collected from the spot and also from the adjacent paddy fields. Other existing standing crops like corn, wheats were also collected for comparison. These samples were properly sealed and dispatched to the designated laboratories for toxicological investigations.

Figure 3. A female elephant, one out of 10 mortalities, died due to an infection of Kodo millet.

Documentation and reporting

All field and laboratory data were compiled in a standardiszed format, including post-mortem findings, chain-of-custody forms and laboratory findings. A comprehensive cause-of-death summary was prepared, integrating all diagnostic modalities, and shared with forest authorities for follow-up actions, including preventive management, surveillance, or legal proceedings.

Diagnostic investigations and results

Post-mortem examination and histopathological analysis

All ten elephants were subjected to post-mortem examinations, which revealed no external injuries or signs of trauma. There were generalised haemorrhages all over the mucosal layers and vital organs. Further, the gastrointestinal tracts were notably distended with ingesta, suggesting recent feeding. Internal organs exhibited signs of haemorrhage and congestion, prompting suspicion of acute toxicosis.

Tissue sections of vital organs revealed pulmonary oedema, extensive haemorrhages, emphysema in lungs, degenerated myocardial fibres and haemorrhages in heart, perivascular hepatocellular necrosis, fatty changes, vascular endothelial degeneration and haemorrhages in liver, acute tubular necrosis and haemorrhages in kidney, congested vessels with patchy haemorrhages in spleen, haemorrhages, epithelial

Figure 4. Mycotoxigenic fungal infection in Kodo millet at the site.

sloughing, mild infiltration, necrotic mucosal changes in gastrointestinal tract and extensive haemorrhage along the epithelial lining in tongue. These findings were generalised and similar in all ten cases. The lesions were consistent with acute toxicity, primarily affecting the vascular and epithelial integrity of major vital organs.

Toxicological analysis

Visceral organs, stomach and intestinal contents from all ten elephants were screened for toxins including hydrogen cyanide (HCN), nitrate-nitrite, heavy metals, organophosphate, organochlorine, carbamate, pyrethroid insecticides. The tests came back negative for all standard chemical and metallic toxins, ruling out anthropogenic chemical poisoning.

However, the gastrointestinal contents were observed to be positive for cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), a mycotoxin produced by fungi such as Aspergillus and Penicillium spp. The investigations detected CPA levels exceeding 100 ppb in elephant tissue samples. One elephant stomach content had 123,165 ppb CPA, approximately 10x higher than the reported LD₅₀ of 13,000 ppb (Nishie et al., 1985).

These results collectively suggested acute mycotoxicosis due to CPA as the primary toxicological finding.

Disease investigation

Looking at the generalised haemorrhages all over the vital organs, tissue samples were also subjected to the detection of elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus (EEHV), which is a fatal virus responsible for haemorrhagic disease and acute death in young elephants worldwide (Sree Lakshmi et al. 2023). However, all the samples tested negative for EEHV by terminase gene-based PCR.

Environmental and crop analysis

Crop sample analysis at International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT), Hyderabad, through Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) detected CPA in crop samples of Kodo millet. Environmental samples, including crop samples of Kodo millet and paddy, showed CPA concentrations ranging from 1,567 to 183,779 ppb. Further, the analyses found mycotoxigenic fungi infestation of the crop, caused by Penicillium spp., Aspergillus spp., Fusarium spp. and Curvularia spp. These fungi were cultured from Kodo millet, paddy, and elephant gut contents (Figure 4).

Overall diagnostic conclusion

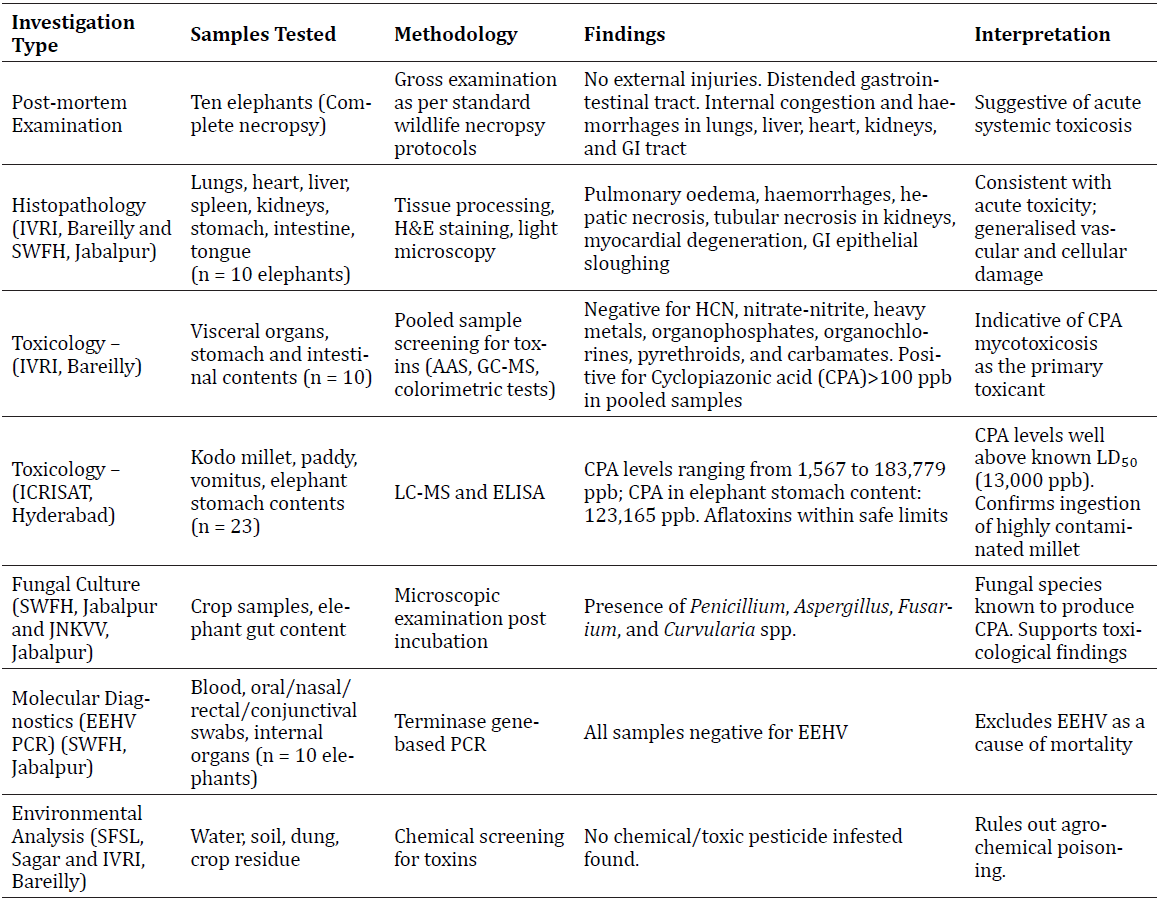

The multidisciplinary diagnostic investigation conclusively identified cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) mycotoxicosis as the cause of death in all ten elephants. The presence of CPA-producing fungal species in Kodo millet consumed by the elephants, coupled with lethal levels of CPA in tissue and environmental samples, and characteristic histopathological lesions, confirmed acute mycotoxicosis and supported a diagnosis of fatal neurotoxicity caused by fungal infestation in consumed crops of Kodo millet (Table 1).

Discussion

The mass mortality event involving ten wild Asiatic elephants in BTR, Madhya Pradesh, in October 2024, represents one of the most significant toxicological wildlife mortality incidents in recent Indian conservation history. This tragedy underscores the pressing challenges posed by the increasing interface between wildlife and human-dominated landscapes, particularly in the context of climate change, crop infestedinfestation, and habitat fragmentation.

Ecological context and elephant behaviour

Recent range expansion of elephants into agrarian landscapes of central India due to dispersal from historically elephant-rich states like Odisha and Jharkhand has increased exposure to non-traditional risks, including contaminated crops. As elephants increasingly move into agrarian landscapes in search of food, conflict with human land use has become inevitable. The migration of a herd of elephants into BTR from Chhattisgarh in 2018 marked a pivotal ecological development. These elephants displayed strong seasonal movement patterns, frequently accessing buffer zones and revenue lands adjacent to protected areas, thereby heightening the risk of consuming contaminated crops.

The mortality event: clinical and field observations

The October 2024 incident of 10 elephant deaths killed nearly 25% of the local elephant population. It occurred in proximity to agricultural fields where Kodo millet had recently been harvested or was still standing. The absence of external injuries and the presence of gastrointestinal distension filled with millet pointed toward a non-traumatic, non-infectious, and possibly toxic aetiology. The rapid progression of symptoms and death in otherwise healthy elephants was consistent with acute poisoning.

Histopathological evidence of acute toxicosis

Histopathological examinations across all 10 elephants revealed a strikingly consistent pattern of lesions, including multi-organ dysfunction. These lesions indicated systemic vascular and cellular damage and supported a diagnosis of acute toxicity affecting multiple organ systems (Larkin et al. 2020; Saganuwan et al. 2023)

Toxicological analysis and confirmation of CPA

The core of the diagnostic investigation was toxicological screening, which revealed the presence of cyclopiazonic acid (CPA), a secondary metabolite produced primarily by Aspergillus flavus and Penicillium cyclopium. CPA was detected in pooled tissue samples at concentrations exceeding 100 ppb. Critically, gastrointestinal contents from the deceased elephants, as well as crop and environmental samples, contained CPA at extremely high levels.

Culture-based assays and morphology confirmed the presence of mycotoxigenic fungal species such as Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium, and Curvularia, which are well-known producers of CPA, aflatoxins, and other harmful metabolites. These results were corroborated by fungal cultures from both the Kodo millet samples and the gut contents of affected elephants.

Although there is limited species-specific data, elephants are expected to be susceptible to mycotoxins affecting the liver and nervous systems due to their slow metabolism and large body mass. Exposure to aflatoxins and fumonisins could lead to significant liver toxicity and neurologic symptoms, similar to effects seen in other large mammals such as horses (Ref.). One of the possible causes of no death record of other wild and domestic herbivores consuming fungal-infected Kodo might be due to ruminants having four chambers, whereas elephants possess a monogastric digestive system.

Mycotoxins and their impact on wildlife

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites produced by fungi (Reddy et al., 2010), especially in moulds of Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium species that pose serious health risks to animals and humans when ingested. These toxins contaminate agricultural products under favourable environmental conditions, particularly high moisture and temperature, leading to animal health and significant economic losses (Hassan et al., 2001).

CPA is a potent mycotoxin with known hepatotoxic, nephrotoxic, and neurotoxic properties. It inhibits calcium-dependent ATPase in the endoplasmic reticulum, leading to cellular apoptosis and necrosis, particularly in liver and kidney tissues (Bhanu, 2024). Although much of the existing toxicological data is based on livestock models such as poultry and swine, extrapolation to megaherbivores such as elephants is supported by their known sensitivity to hepatotoxic agents due to their slow metabolic rate and large gut fermentation systems (Greene et al. 2019).

The resistance of mycotoxins to degradation, even under high temperatures or post-harvest processing, makes them insidious threats to both humans and animals (Khan et al., 2024). The lethal concentration of CPA in the sampled elephant stomach content firmly establishes this compound as the proximate cause of death.

Historical precedent of Kodo poisoning in elephants and implications for human safety

This is not the first documented case of elephant mortality due to mycotoxins. A similar incident was also reported in December 1933, when 14 elephants were suspected to have ingested Kodo millet and subsequently found dead near the Vannathiparai Reserve Forest in Tamil Nadu, close to the Kerala border (Morris, 1934).

Kodo millet has beneficial properties for human health, and the government of India is promoting millets in the central Indian landscape, where precipitation is low. However, there were reports of ‘Kodo poisoning’, especially from Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh (Deepika et al. 2022). Bhide (1962) and Bhide & Aimen (1959) noted that the husk and foliage of Kodo millet frequently acquire toxic properties, a phenomenon that is frequently associated with heavy rainfall. In the states of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, this form of poisoning is locally known as Malona, underscoring long-standing indigenous knowledge of this hazard. Rao & Husain (1985) were the first to establish the connection between the mycotoxin cyclopiazonic acid (CPA) and Kodo millet seeds, which causes “kodua poisoning.”

Table:1 Summary of Diagnostic Investigations and Findings in Elephant Mortality at Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh

It is important to clarify that consumption of Kodo millet per se is not inherently fatal. The risk arises when the grain is contaminated with toxigenic fungi such as Penicillium spp. or Aspergillus spp., which are capable of producing CPA, which is an indole-tetramic acid mycotoxin that inhibits sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca²⁺-ATPase, leading to disruption of calcium homeostasis, hepatocellular damage, and neuromuscular dysfunction (Seidler et al., 1989).

Comparative host susceptibility plays a key role in the outcome of CPA exposure. Large herbivores, such as elephants, are highly vulnerable due to their bulk consumption of contaminated feed and limited detoxification capacity. Conversely, humans are comparatively less susceptible, as fungal infestations can be minimised by traditional practices such as sun-drying or mechanical cleaning, which significantly reduce mycotoxin loads. Thus, it is important to understand that while Kodo millet remains a safe dietary staple for humans when properly processed, its fungal colonisation and subsequent CPA production represent a critical risk factor for wildlife health in contaminated landscapes.

Contributing factors: climate, agriculture, and conservation conflict

This tragic mortality event is symptomatic of broader ecological and anthropogenic trends. Climate variability, particularly unseasonal rainfall during harvest periods, creates moist conditions conducive to fungal colonisation of standing crops (Zingales et al. 2022). Coupled with improper post-harvest storage, these environmental changes have led to increasing incidences of mycotoxin infestations.

Elephants, driven into farmlands due to habitat shrinkage and food shortages, are at risk of ingesting contaminated crops, especially in buffer zones and village margins adjacent to protected areas. The revenue village of Salkhaniya, less than a kilometre from BTR’s boundary, was cultivating Kodo millet during the incident period, and preliminary field reports confirmed crop-raiding activity by elephants the night before the mortality event.

The lack of buffer policies restricting high-risk crops near protected areas, the absence of routine crop testing, and limited farmer awareness about fungal infestation collectively represent critical gaps in the landscape-level management of wildlife-agriculture interactions.

Legal and institutional dimensions

The incident prompted judicial scrutiny under the National Green Tribunal (NGT), Central Zone Bench, Bhopal, which linked the deaths to CPA mycotoxicosis exacerbated by climate-driven fungal infestation. The Tribunal acknowledged that these deaths occurred despite the declaration of BTR and its buffer zones as an Eco-Sensitive Zone in 2016 under the Environment Protection Act, 1986. The incident serves as a legal precedent for integrating environmental, agricultural, and wildlife safety concerns under one regulatory umbrella. Detailed guidelines have already been proposed by the NGT, Central Zone Bench, Bhopal, under point number 34 (https://indiankanoon.org/doc/46470666/).

Management and policy implications

A multi-pronged strategy is essential to prevent recurrence of such incidents. It was also mentioned by NGT that the incident took place in the eco-sensitive zone, hence their directive includes:

- Ecological zoning and buffer management: Restricting the cultivation of known mycotoxin-prone crops such as Kodo millet and paddy within a buffer radius of protected areas.

- Farmer sensitiszation and incentivization: Awareness programs and subsidies for growing safer alternative crops (g., legumes) in conflict-prone zones.

- Crop surveillance and mycotoxin screening: Establishment of field-based testing laboratories to regularly monitor aflatoxins and CPA levels in crops grown near wildlife habitats.

- Post-harvest management: Introduction of improved storage techniques, moisture control, and fungal inhibition strategies, including bio-control agents and hermetic storage systems.

- Climate-responsive agricultural policies: Development of fungal forecasting models using meteorological data to guide sowing, harvesting, and drying schedules.

- Veterinary preparedness: Strengthening wildlife health infrastructure to enable real-time disease investigation and sample analysis.

- Landscape-level wildlife corridors: Ensuring undisturbed migratory routes for elephants to reduce reliance on human-dominated fields for foraging.

- Interdepartmental coordination: Forest, agriculture, and veterinary departments must collaborate under an integrated “One Health” framework addressing zoonotic, environmental, and ecological intersections, recognising that human, animal, and environmental health are deeply interconnected.

Conclusion

The BTR elephant mortality event is a serious reminder of the ecological fragility at the wildlife-agriculture interface. The confirmed role of CPA, —a fungal mycotoxin,— in this mass mortality highlights the urgent need to recognise and mitigate non-traditional toxic threats to wildlife. As climate change alters fungal growth patterns and increases the likelihood of mycotoxin infestation, policy and management approaches must evolve from reactive to anticipatory. In such scenarios, as per the NGT guidelines, there should be continuous crop surveillance in eco-sensitive zones, especially during the harvesting season, along with community awareness and sensitisation (https://indiankanoon.org/doc/46470666/).

Protecting elephants, keystone species of immense ecological and cultural importance, requires not only preserving forest cover but also managing the agrarian matrix they traverse. A comprehensive, evidence-based response that integrates science, policy, and community participation will be pivotal in ensuring the coexistence of wildlife and human livelihoods in shared landscapes.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank to Mr Ashok Barnawal (Additional Chief Secretory, M.P. Forest Department), Mr Aseem Shrivastav (PCCF and Head of Forestry Forces, M.P. Forest), Dr Govind Sagar Bhardwaj (Member Secretory, National Tiger Conservation Authority), Mr Nandkishor Vyankatesh Kale, Assistant Inspector General of Forests (AIGF), National Tiger Conservation Authority, Mr. Nair Vishnuraj Narendran (Regional Director, Wildlife Crime Control Bureau) for their valuable support and assistance. Our sincere thanks to team of expert veterinarians including Dr Abhay Sengar, Dr Akhilesh Mishra, Dr Sandeep Agarwal, Dr Sanjeev Gupta, Dr Amol Rokde, Dr Himanshu Joshi (WCT), Dr Hamza Nadeem Farooqi for their extensive support during sample collections for lab analysis. Dr Raman Sukumar (Senior Scientist, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, Dr A B Srivastav (Former Director School of Wildlife Forensic and Health), Mr NKS Vasu (Former Chief Wildlife Warden, Assam Forest Department), Mrs Manjula Srivastav (Advocate) for their technical guidance and support.

We provide our sincere thanks to Ministry of Environment and Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, Government of Madhya Pradesh, Office of District Collector Umaria, Office of Superintendent of Police, Umaria, ICAR-Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), Bareilly, International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-arid Tropics (ICRISAT), Hyderabad, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, Jawaharlal Nehru Krishi Vishwa Vidyalaya (JNKVV), School of Wildlife Forensic and Health, Nanaji Deshmukh Veterinary Science University, Jabalpur, State Forest Research Institute, Jabalpur, State Forensic Science Laboratory, Sagar and officer and frontline forest staff of BTR, Umaria Forest Division, North Shadole Forest Division, State Tiger Task Force, Forest Department, Madhya Pradesh. Last but not least, a special thank to all villagers adjacent to elephant death areas, who supported us during field sampling.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr Parag Nigam is an academic editor at the Journal of Wildlife Science. However, he did not participate in the peer review process of this article except as an author. The authors declare no other conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data and reports of laboratory analyses are available from the corresponding author on request.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

AVK, SS, LK, DAK, SA, VPK, SR Contributed in entire management and resource availability during rescue operation and also provided inputs on the draft; SJ, NR, HS, KM SS analysed the different samples; TK contributed in sample and data collection. AM, NR, TK prepared first draft; RS, AM, NR, TK edited and refined the manuscript; PN, PRK provided inputs on the draft; NG collected the samples and performed postmortems.

Edited By

M. Anand Kumar

Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore, India

*CORRESPONDENCE

L. Krishnamoorthy

✉ stsf.bpl@gmail.com

SPECIAL ISSUE

This paper is published in the Special Issue '30 Years of Elephant Conservation in India'

CITATION

Ambade, V. K. N., Sen, S., Krishnamoorthy, L., Pandey, R. K., Dubey, A. K., Sahay, A., Varma, P. K., Sarothiya, R., Jawre, S., Rajput, N., Majumdar, A., Karmarkar, T., Sudini, H., Mathesh, K., Shrivastav, S., Gupta, N. & Nigam, P. (2025). Mortality investigations in wild Asiatic elephants (Elephas maximus) due to infected Kodo millet consumption in Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh- A case study. Journal of Wildlife Science, Online Early Publication, 01-08. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.CRPW6521

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Ambad, Sen, Krishnamoorthy, Pandey, Dubey, Sahay, Varma, Sarothiya, Jawre, Rajput, Majumdar, Karmarkar, Sudini, Mathesh, Shrivastav, Gupta & Nigam. This is an open-access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The information contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bhanu, M. L. S. (2024). Potential risk of Cyclopiazonic acid toxicity in Kodo Millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum L.) Poisoning. Proceedings. 102(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2024102027

Bhide, N. K. (1962). Pharmacological Study and Fractionation of Paspalum scrobiculatum Extract. British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy, 18(1), 7-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1962.tb01145.x

Bhide, N. K. & Aimen, R. A. (1959). Pharmacology of a tranquillizing principle in Paspalum scrobiculatum grain. Nature, 183(4677), 1735-1736. https://doi.org/10.1038/1831735b0

Champion, H. G. & Seth, S. K. (1968). A revised survey of the forest types of India. Manager of publications, p.404.

Deepika,C., Hariprasanna, K., Das, I. K., Jacob, J., Ronanki, S., Ratnavathi, C. V., Bellundagi, A., Sooganna, D. & Tonapi, V. A. (2022). ‘Kodo poisoning’: cause, science and management. Journal of food science and technology, 59, 2517–2526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-021-05141-1

Greene, W., Dierenfeld, E. S. & Mikota, S. (2019). A review of Asian and African elephant gastrointestinal anatomy, physiology and pharmacology. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, 7(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v7i1.329

Hassan, Z. U., Al Thani, R., Atia, F. A., Alsafran, M., Migheli, Q. & Jaoua, S. (2021). Application of yeasts and yeast derivatives for the biological control of toxigenic fungi and their toxic metabolites. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 22, 101447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101447

Khan, R., Anwar, F. & Ghazali, F. M. (2024). A comprehensive review of mycotoxins: Toxicology, detection, and effective mitigation approaches. Heliyon, 10(8), e28361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28361

Larkin, P. M. K., Multani, A., Beaird, O. E., Dayo, A. J., Fishbein, G. A. & Yang, S. (2020). A Collaborative Tale of Diagnosing and Treating Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis, from the Perspectives of Clinical Microbiologists, Surgical Pathologists, and Infectious Disease Clinicians. Journal of Fungi, 6(3), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6030106

MoEF&CC (2017). Synchronized elephant population estimation: India 2017. Project Elephant Division, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India .

Morris, R. C. (1934). Millet Poisoning in elephants. Journal of Bombay Natural History Society, XXXVII, p.723.

Natarajan, L., Kumar, A., Nigam,P. & Pandav, B. (2023). An Overview of Elephant Demography in Chhattisgarh (India): Implications for Management. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 120. https://doi.org/10.17087/jbnhs/2023/v120/167989

Nishie, K., Cole, R. J. & Dorner, J. W. (1985). Toxicity and neuropharmacology of cyclopiazonic acid. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 23(9), 831-839. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6915(85)90284-4

Panda, P. P., Noyal, T. & Dasgupta, S. (2020). Best Practices of Human–Elephant Conflict Management in India. Published by Elephant Cell, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, p.40.

Prakasam, U. (2006). Management Plan of Bandhavgarh National Park. Forest Department, Government of Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal.

Qureshi, Q., Kolipakam, V., Kumar, U., Jhala, Y. V., Pandey, R. K., Habib, B., Bhardwaj, G. S., Yadav, S. P. & Tiwari, V. R. Status of Elephants in India: DNA based Synchronous All India population estimation of elephants (SAIEE), (2021-2025). Wildlife Institute of India. ISBN - 81-85496-85-4

Reddy, K. R. N., Salleh, B., Saad, B., Abbas, H. K., Abel, C. A., & Shier, W. T. (2010). An overview of mycotoxin contamination in foods and feeds in India. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 58(11), 6547–6559.

Rao, B. L. & Husain, A. (1985). Presence of cyclopiazonic acid in Kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum) causing ‘kodua poisoning’ in man and its production by associated fungi. Mycopathologia, 89(3), 177-180. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00447028

Saganuwan, S. A., Junior, A. S., Tsekohol, A. S. & Wanmi, N. (2023). Acute toxicity study, haematological, biochemical and histopathological effects of Brassica oleracea var. capitata, Allium porrum and Cucurbita maxima in Rattus norvegicus. RPS Pharmacy and Pharmacology Reports, 2(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpsppr/rqad025

Seidler, N. W., Jona, I., Vegh, M. & Martonosi, A. (1989). Cyclopiazonic acid is a specific inhibitor of the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 264(30), 17816-17823.

Sonakiya, A. (1993). Management Plan of Bandhavgarh National Park for the period of 1993-94 to 2002- 2003. Vol. I. Text (Part I and II) Forest Department, Government of Madhya Pradesh.

Sree Lakshmi, P., Karikalan, M., Sharma, G. K., Sharma, K., Chandra Mohan, S., Kumar, R. K., Miachieo, K., Kumar, A., Gupta, M. K., Verma, R. K., Sahoo, N., Saikumar, G. & Pawde, A. M. (2023). Pathological and molecular studies on elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus haemorrhagic disease among captive and free-range Asian elephants in India, Microbial Pathogenesis, 175, 105972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2023.105972

Sukumar R. (1990). Ecology of the Asian elephant in southern India. II. Feeding habits and crop raiding patterns. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 6(1), 33-53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400004004

Zingales, V., Taroncher, M., Martino, P. A., Ruiz, M. J. & Caloni, F. (2022). Climate change and effects on molds and mycotoxins. Toxins, 14(7), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14070445

Edited By

M. Anand Kumar

Nature Conservation Foundation, Mysore, India

*CORRESPONDENCE

L. Krishnamoorthy

✉ stsf.bpl@gmail.com

SPECIAL ISSUE

This paper is published in the Special Issue '30 Years of Elephant Conservation in India'

CITATION

Ambade, V. K. N., Sen, S., Krishnamoorthy, L., Pandey, R. K., Dubey, A. K., Sahay, A., Varma, P. K., Sarothiya, R., Jawre, S., Rajput, N., Majumdar, A., Karmarkar, T., Sudini, H., Mathesh, K., Shrivastav, S., Gupta, N. & Nigam, P. (2025). Mortality investigations in wild Asiatic elephants (Elephas maximus) due to infected Kodo millet consumption in Bandhavgarh Tiger Reserve, Madhya Pradesh- A case study. Journal of Wildlife Science, Online Early Publication, 01-08. https://doi.org/10.63033/JWLS.CRPW6521

COPYRIGHT

© 2025 Ambad, Sen, Krishnamoorthy, Pandey, Dubey, Sahay, Varma, Sarothiya, Jawre, Rajput, Majumdar, Karmarkar, Sudini, Mathesh, Shrivastav, Gupta & Nigam. This is an open-access article, immediately and freely available to read, download, and share. The information contained in this article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), allowing for unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited in accordance with accepted academic practice. Copyright is retained by the author(s).

PUBLISHED BY

Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, 248 001 INDIA

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

The Publisher, Journal of Wildlife Science or Editors cannot be held responsible for any errors or consequences arising from the use of the information contained in this article. All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organisations or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated or used in this article or claim made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bhanu, M. L. S. (2024). Potential risk of Cyclopiazonic acid toxicity in Kodo Millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum L.) Poisoning. Proceedings. 102(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2024102027

Bhide, N. K. (1962). Pharmacological Study and Fractionation of Paspalum scrobiculatum Extract. British Journal of Pharmacology and Chemotherapy, 18(1), 7-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-5381.1962.tb01145.x

Bhide, N. K. & Aimen, R. A. (1959). Pharmacology of a tranquillizing principle in Paspalum scrobiculatum grain. Nature, 183(4677), 1735-1736. https://doi.org/10.1038/1831735b0

Champion, H. G. & Seth, S. K. (1968). A revised survey of the forest types of India. Manager of publications, p.404.

Deepika,C., Hariprasanna, K., Das, I. K., Jacob, J., Ronanki, S., Ratnavathi, C. V., Bellundagi, A., Sooganna, D. & Tonapi, V. A. (2022). ‘Kodo poisoning’: cause, science and management. Journal of food science and technology, 59, 2517–2526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13197-021-05141-1

Greene, W., Dierenfeld, E. S. & Mikota, S. (2019). A review of Asian and African elephant gastrointestinal anatomy, physiology and pharmacology. Journal of Zoo and Aquarium Research, 7(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.19227/jzar.v7i1.329

Hassan, Z. U., Al Thani, R., Atia, F. A., Alsafran, M., Migheli, Q. & Jaoua, S. (2021). Application of yeasts and yeast derivatives for the biological control of toxigenic fungi and their toxic metabolites. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 22, 101447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101447

Khan, R., Anwar, F. & Ghazali, F. M. (2024). A comprehensive review of mycotoxins: Toxicology, detection, and effective mitigation approaches. Heliyon, 10(8), e28361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28361

Larkin, P. M. K., Multani, A., Beaird, O. E., Dayo, A. J., Fishbein, G. A. & Yang, S. (2020). A Collaborative Tale of Diagnosing and Treating Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis, from the Perspectives of Clinical Microbiologists, Surgical Pathologists, and Infectious Disease Clinicians. Journal of Fungi, 6(3), 106. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof6030106

MoEF&CC (2017). Synchronized elephant population estimation: India 2017. Project Elephant Division, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India .

Morris, R. C. (1934). Millet Poisoning in elephants. Journal of Bombay Natural History Society, XXXVII, p.723.

Natarajan, L., Kumar, A., Nigam,P. & Pandav, B. (2023). An Overview of Elephant Demography in Chhattisgarh (India): Implications for Management. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 120. https://doi.org/10.17087/jbnhs/2023/v120/167989

Nishie, K., Cole, R. J. & Dorner, J. W. (1985). Toxicity and neuropharmacology of cyclopiazonic acid. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 23(9), 831-839. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6915(85)90284-4

Panda, P. P., Noyal, T. & Dasgupta, S. (2020). Best Practices of Human–Elephant Conflict Management in India. Published by Elephant Cell, Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, p.40.

Prakasam, U. (2006). Management Plan of Bandhavgarh National Park. Forest Department, Government of Madhya Pradesh, Bhopal.

Qureshi, Q., Kolipakam, V., Kumar, U., Jhala, Y. V., Pandey, R. K., Habib, B., Bhardwaj, G. S., Yadav, S. P. & Tiwari, V. R. Status of Elephants in India: DNA based Synchronous All India population estimation of elephants (SAIEE), (2021-2025). Wildlife Institute of India. ISBN - 81-85496-85-4

Reddy, K. R. N., Salleh, B., Saad, B., Abbas, H. K., Abel, C. A., & Shier, W. T. (2010). An overview of mycotoxin contamination in foods and feeds in India. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 58(11), 6547–6559.

Rao, B. L. & Husain, A. (1985). Presence of cyclopiazonic acid in Kodo millet (Paspalum scrobiculatum) causing ‘kodua poisoning’ in man and its production by associated fungi. Mycopathologia, 89(3), 177-180. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00447028

Saganuwan, S. A., Junior, A. S., Tsekohol, A. S. & Wanmi, N. (2023). Acute toxicity study, haematological, biochemical and histopathological effects of Brassica oleracea var. capitata, Allium porrum and Cucurbita maxima in Rattus norvegicus. RPS Pharmacy and Pharmacology Reports, 2(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/rpsppr/rqad025

Seidler, N. W., Jona, I., Vegh, M. & Martonosi, A. (1989). Cyclopiazonic acid is a specific inhibitor of the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 264(30), 17816-17823.

Sonakiya, A. (1993). Management Plan of Bandhavgarh National Park for the period of 1993-94 to 2002- 2003. Vol. I. Text (Part I and II) Forest Department, Government of Madhya Pradesh.

Sree Lakshmi, P., Karikalan, M., Sharma, G. K., Sharma, K., Chandra Mohan, S., Kumar, R. K., Miachieo, K., Kumar, A., Gupta, M. K., Verma, R. K., Sahoo, N., Saikumar, G. & Pawde, A. M. (2023). Pathological and molecular studies on elephant endotheliotropic herpesvirus haemorrhagic disease among captive and free-range Asian elephants in India, Microbial Pathogenesis, 175, 105972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2023.105972

Sukumar R. (1990). Ecology of the Asian elephant in southern India. II. Feeding habits and crop raiding patterns. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 6(1), 33-53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400004004

Zingales, V., Taroncher, M., Martino, P. A., Ruiz, M. J. & Caloni, F. (2022). Climate change and effects on molds and mycotoxins. Toxins, 14(7), 445. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14070445